Sheberghan, Yemshi Tepe & Talayeh Tepe (also Tillya Tepe, Tillia Tepe or Tillā Tapa)

Contents

Balkh

|

Sheberghan

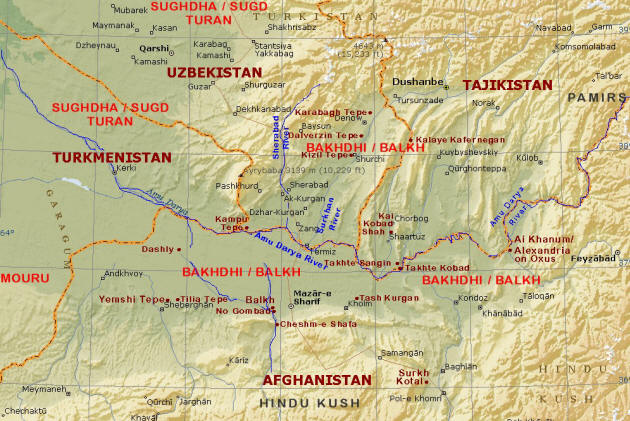

Sheberghan (Persian: شبرغان. Also spelt Shaburghan Shebirghan Shibarghan) is the capital of Afghanistan's Jowzjan Province. It is thought that the name is derived from Shapurgan meaning the City of Shapur. Shapur was the name of several Sassanian kings. Besides its own claim to a place in history, two archaeological sites, Talayeh Tepe (also spelt Tillya Tepe) and Yemshi Tepe are located on the outskirts of the city. To the west of Sheberghan lie Emchi Tepe (a 18 ha. site with a circumference of 1.5 km, containing the ruins of a city fortified with ramparts). The small fort of Jiga Tepe is a further 5 km from Emchi Tepe.

In ancient times, Sheberghan would have been part of the ancient Zoroastrian kingdom of Balkh, whose king, King Vishtasp, was the first king to accept the Zoroastrian faith.

Situated in the fertile Sapid (or Safid meaning white) River plains, Sheberghan straddled the ancient Aryan trade crossroads, the eastern branch of the which passed through Ai Khanum and Balkh. It is about 130 km (80 miles) west of Mazar-e Sharif. In the 13th century CE, Marco Polo travelling the Silk Roads, passed through the city and related that the melons he eat there were as sweet as honey. In the Zoroastrian era, the Sapid River plains would have been part of the fertile and agriculturally rich plains of the kingdom of Balkh.

Since ancient times, people from elsewhere on the Aryan trade roads settled in Sheberghan and the city became home to people from the north, east, west and south - the Sogdians, Scythians, Persians, Arabs, Pashtuns as well as people from Merv and Pamir-Badakshan. Today, the majority of its citizens identify themselves as Uzbek (ancient Sugd), with Tajiks making up a significant minority.

Ruins at Yemshi Tepe

The ruins of the fortified town of Yemshi Tepe (tepe meaning mound), lies five kilometres northeast of Sheberghan. According to a description provided by the Soviet archaeologist Sarianidi in 1985, "Its tall, mighty walls pierced by several narrow gateways were fortified by defence towers and formed an impregnable ring ... . Inside, in the northern section, stood the citadel, at whose foot were the remains of what had apparently been the palatial residence of the local ruler. Some 50 acres (20 ha) in area, this ancient city, indubitably a vast one for its time, comprised, along with the small villages of its sprawling suburbs, the administrative seat of the entire neighbouring region, once part of the legendary empire of Bactria."

Ruins at Talayeh Tepe / Tillya Tepe

Talayeh Tepe lies just half a kilometre from the ruins of Yemshi Tepe. Talayeh Tepe (also spelt Tillya Tepe, Tillia Tepe or Tillā Tapa and طلا تپه in Persian), means the 'mound of gold' in Persian and Dari (tepe or depe means a mound. Many ancient ruins have been found by excavating a tepe). Upon excavation of the Talayeh Tepe, it was found that the mound had been formed by earth covering an ancient building whose construction was subsequently dated to 1,500-1,000 BCE. Fifteen hundred years after its construction, that is around two thousand years ago, in the first century CE, the building that had been destroyed some five hundred years earlier, had already been covered by earth and the resulting mound was used as a royal burial site. The bodies excavated were found to have been buried which a large number of gold and other precious ornaments. These ornaments have been called the Bactrian Horde or Treasure.

In 1979, the site was surveyed by a Soviet-Afghan team of archaeologists led by Victor Sarianidi a year before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Victor Sarianidi was the Soviet archaeologist who also excavated Gonur Tepe, in neighbouring Turkmenistan.

When the mound of Talayeh Tepe was excavated by Sarianidi's team, Sarianidi promptly speculated that the ruined building had most likely been a fire temple and further reports added that it had likely been a Zoroastrian Fire Temple. The mound was also called an ancient necropolis, a burial 'city'. However, other than reports of the six or seven graves which contained the gold artefacts, we are not clear how many other graves the area contained and is the number qualifies it to be a necropolis rather than a graveyard.

The building, whose construction we mentioned earlier was dated by Sarianidi at 1,500 BCE, consisted of two halls whose flat roofs were supported by fifteen square columns. The larger room contained a raised platform (a three metre or twenty-foot high brick platform?), which Sarianidi reported contained traces of ash and was therefore a fire altar. This led Sarianidi to further speculate that the building was a fire temple. Though Sarianidi was a pioneer in many respects, his archaeological techniques have been criticized by other archaeologists, and we have found many of his claims, for instance regarding finding evidence of a haoma ritual site in Gonur to be outlandish and more speculation than science. (Also see our section on Very Poor Archaeological Practices in the Gonur (Turkmenistan) page.

The artefacts found in the graves are said to date from 100 BCE to 100 CE, a time span that would have fallen within the Parthian period (c. 247 BCE - c. 229 CE). In six of the necropolis' graves beside the large building, Sarianidi's crew found about 20,600 gold (70% gold content) ornaments, some weighing a kilo, with a variety of designs - some local and other designs seen elsewhere along the Aryan trade roads. Some of the designs are a synthesis of Parthian, Greek, Chinese, Indian and local themes. The graves in which the ornaments were discovered belonged to five women and one man (another report said five men and one woman), identified by Sarianidi as local royalty and nobility. This rather amazing and large collection has been called the Bactrian Horde by some authors.

Sarianidi's initial comments and the worldwide attention given to the gold ornaments have spawned a large number of pseudo-scholarships publishing their views on Zoroastrianism and Zoroastrian history. The reader is advised to be cautious in accepting the information in articles of the type quoted below.

Publications::

- Sarianidi V.:

- Work of the Soviet-Afghan mission: Archaeological Discoveries, 1978 - M.1979;

- Gold of the Nameless Kings. Discoveries in Afghanistan - Courier, 1980, January;

- Treasure of the Golden Hill. Science and Humanity. M, 1983; Afghanistan:

- Treasures of the Nameless Kings – M, Nauka, 1983, Bactria through the Darkness of Centuries. M.: Mysl, 1984.

- Kuzmina E., Sarianidi V., Two Examples of Headgear from the Burial of Tillya-Tepe and Their Semantics, Brief Communications Institute of Archeology, issue170, 1982, p.19-27;

- Sarianidi V. Koshelenko G., Coins from the Excavations of the Necropolis Located on the Site of Tilla-Tepe. Ancient India. -M: Nauka, 1982, p.302-319

- Sarianidi V., Hodzhaniyazov T., Excavations in the Royal Necropolis of ancient Bactria: Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the Tajik SSR.Seriya public nauki.Dushanbe, 1980, № 4, p.41-51

- Sarianidi V. Die Schatze der Kushanen-Konige.Afghanistan journal, 1979, bd.4; idem.-Le tomb Regallo della "Collino d'ore 'Mesopotamia, XV, Firenze, 1980; idem The treasure of the Golden Mound, Archaeology, vol .33,1980; idem The treasure from the Golden Hill. American journal of Archaeology, 1980, # 2

- Neva E., Negmatullaeva. On the Question of Attribution of Two Burial Sites of Tillya-Tepe, on the example of jewelry: Topical issues to humanitarian sciences at the present stage, Dushanbe, 1987, p. 151-153

- Pugachenkova G. L. Rempel, Golden Nameless KIngs from Tillya Tepe, From the History of Cultural Relations between the Peoples of Central Asia and India, Tashkent: Fan, 1986, p.5-24

- Bactrian Gold. L.1985 Bactrian Gold Afghanistan. Hidden Treasures from the National Museum of Kabul. National Geographic, 2008

Examples of the Bactrian Gold Ornaments

|

Headdress ornament. Tillya Tepe Tomb II, first century A.D.

Gold with turquoise, garnet, lapis lazuli, carnelian and pearls

12.5 x 6.5 cm (5 x 2–5/8 in.)

Image credit: Metropolitan Museum |

|

|

| Ornaments and how they were worn. Base image credit: Wikipedia |

|

Example of Poor Quality Pseudo-Scholarship

The following is an example supposed scholarship which pretends to a knowledge of Zoroastrianism and Zoroastrian history, and which contributes to the misinformation about Zoroastrianism that is circulating amongst a group of writers and academics who are given to speculation rather than scholarship. In their book Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines, authors Jeannine Davis-Kimball and Mona Behan write as follows:

"Among the earliest ruins (at Tillya Tepe) was a fire temple initially built before 1000 BC. Most likely associated with Zoroastrianism, the temple featured two column-flanked hallways and fortified towers at each corner, and was ringed by a high defensive wall. The centerpiece of the main room was an altar set on a twenty-foot high brick platform, the site of sacred fires. To begin the fire ceremony, the priests lit some sandalwood twigs on a dish on a pedestal, allowed them to burn down, and then poured some incense on the embers to unleash a cloud of sweet fragrance. The priest then added more sandalwood to reignite the flames, and then using a burning twig, transfered the fire to a large stack of wood that had been set at the main altar. In great temples, such as this one at Tillya Tepe, once the main fire was initiated it was supposed to burn continously, as the fire itself was considered the personification of Ormuzd, called Ahura Mazda ("the good god"), the great winged deity who was the spirit of light and goodness.

"The temple enjoyed a long history, though not without mishap. Archaeological evidence reveals that it had been laid waste and then magnificently rebuilt in the middle of the first millennium BC. Not long afterward, fire struck, and by the time Alexander the Great marched into the city around 328 BC, he found only a pile of ruins where Ahura Mazda had protected his followers from the forces of evil (Sarianidi 1985)"

There is not sufficient room here - and it would be a distraction - to refute every error in the two paragraphs above. There is hardly a phrase that we would not have to correct. There is no reference in the assertions made above to an analysis of ash (if any) found at the site, a confirmation of any analysis by independent laboratories, or a reference to the published results that the ash was produced by burning sandalwood. There is also no mention of where in the region that sandalwood was grown or could have come from. To our knowledge sandalwood is not native to Northern Afghanistan. We wonder if instead of basing their conclusions on evidence found at the site, Sarianidi or the authors have tried to transpose a modern Parsee / Indian practice of using sandalwood (from Mysore in southern India) on their speculations - thereby creating a fictitious ancient scenario. Unless there are carvings or written inscriptions, depicting the altar scene they describe - and there are none referenced - we are compelled to conclude that these individuals have allowed fantasy to supersede good sense. We have no idea where the authors obtained the information permitting them to describe in some detail the one-time event of the initial lighting of an eternal fire (that burns in Zoroastrian Atash Bahram temples) at this presumed Zoroastrian temple. The authors also seem to be completely unaware that there were, and are, no images of God in Zoroastrianism - winged or otherwise. Further, the use of the pronoun "he" for God exposes a bias on the part of the writers for God in Zoroastrianism has no anthropomorphic attributes including gender. It is time that people such as these to stop demeaning the Zoroastrian religion.

We cannot understand why certain western writers, academics and archaeologists, cannot simply state the facts of their observations and then refrain from speculating and concocting fictitious scenarios similar to the one above.

Safeguarding the Bactrian Treasure

|

Opening the safes containing the Bactrian gold.

Left, with hands on safe: Afghan Minister of Culture Sayed Makhodoom Raheen

Center-right with white hair: archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi.

Behind Sarianidi to right: National Geographic Fellow Fredrik Hiebert

Photo credit: National Geographic |

The following is an excerpt from Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopaedia:

The collection of 30,600 Bactrian gold ornaments discovered at Talayeh Tepe / Tillya Tepe "... was thought to have been lost at some point in the 1990s, but in 2003 it was found in secret vaults under the central bank building in Kabul. It is believed that, in mid 1990s, seeing its historical value and importance to Afghanistan's cultural heritage, the last president of Afghanistan, Mohammad Najibullah had moved the hoard from Kabul Museum, located near the frontline, to an underground vault at the Central Bank of Afghanistan in Kabul. The doors of the vault were locked with seven keys which were distributed to trusted individuals who were based abroad. The vault, which could only be opened if all the keys were available, provided security to the Bactrian Hoard, protecting it on numerous occasions from attempts by the Taliban to steal it. During the invasion of Afghanistan by American forces, the Taliban, who were unaware that all seven keys were needed in order to open the vault, made one last attempt to get their hands on the treasure by planting bombs on the vault door. Before they could detonate the bombs, American troops arrived at the central bank and the militants were forced to flee. Had the Taliban managed to bomb the vault, the underground chamber in which the hoard was stored would have almost certainly collapsed, destroying the hoard forever.

"In 2003, after the Taliban was successfully defeated, the new government wanted to open the vault, but the key-holders (called "tawadars") could not be summoned because their names were purposefully unknown. Hamid Karzai had to issue a decree authorizing the attorney general to go ahead with safecracking. But in time, the seven key-holders were successfully assembled and the vault opened. Since then, the National Geographic Society has catalogued the collection, which appears to be complete -- 22,000 objects. Also witnessing the re-opening were National Geographic Explorer and Archaeology Fellow Fredrik Hiebert and the archaeologist who originally found the hoard, Viktor Sarianidi."

The following is an excerpt from Discover Magazine:

"It is now clear that Omar Khan Massoudi, director of Kabul’s National Museum, and a few other Afghans risked their lives to protect the artefacts from the Taliban, who were intent on destroying images—and who, in 2001, succeeded in blowing up the famed Bamiyan Buddhas, towering stone sculptures carved into the mountainside by monks about 1,500 years ago.

"Massoudi and his staff “are the real heroes,” Sarianidi says, for saving the remains of a remarkable culture from oblivion."

» Top

|