Contents

Baresman

Haoma

» Suggested further reading: Haoma (Hom)

Introduction - Baresma, Baresman, Barsom

|

Today, the baresman or barsom is a bundle of metal rods (a modern innovation) or sticks used in Zoroastrian religious ceremonies and rituals. In the ceremonies, the baresman bundle represents the vegetable creation and the Amesha Spenta Amertat - eternal life and an undying spirit. Implied qualities represented by the baresman include strength, good health and overcoming disease.

During our research into the baresman, we found that the original baresman, and the sticks or twigs in the baresman bundle, had in the ancient past a far more practical use and a deeper symbolic function as well. In its use, the baresman was closely associated with haoma. Both lay at the heart of ancient Zoroastrian health and healing practices.

|

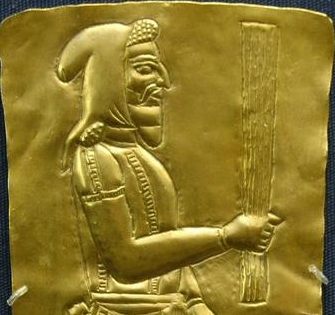

| Rock carving, Museum for Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara Individual carrying a baresman bundle and haoma cup (?) |

Barsom is a Pahlavi (middle Persian) word, and baresma or baresman are the older words used in the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta. The Avestan words are associated with the word barez, sometimes translated at 'exalted' and other times as 'grow'.

Early classical reports, rock carvings and artefacts from west to east of Zoroastrian lands, depict magi in particular and Zoroastrians in general, carrying baresman bundles with them. They carried the baresman bundles with them so frequently, that the baresman became the principle identifying symbol of the magi and the Zoroastrian faith from Central Asia to the Pamirs.

Strabo (63/64 BCE - 24 ACE), wrote in his Geography, that in the west of the Zoroastrian realms, the magi of Cappadocia (Eastern Turkey today) during worship "make incantations for about an hour, holding before the fire their bundles of rods (sticks or twigs)." The magi were early Zoroastrian priests and elsewhere Strabo states the bundles consisted of "slender myrtle wands".

Not too far from Cappadocia (Central Asia), to the south east bordering the Kurdistan region, we find rock carvings at Taq-e Bostan (Taq-i-Bustan or Taqwasân) dating from the time of the early Sassanian dynasty (226 to 650 ACE) of Iran. Taq-e Bostan means arch of the garden and is located on the Silk Road near the western Iranian city of Kermanshah.

|

|

Sassanian rock carving at Taq-e-Bostan The figure on the left holds a baresman |

The photograph to the right shows a portion of the Taq-e Bostan cravings. The figure in the center is said to be King Ardeshir I or II. The haloed person behind him and to the left (a head magus or mobed?) is holding a baresman bundle.

From the east of the Zoroastrian realms - two thousand kilometres to the east along the Silk Roads - comes from a collection of fifth and fourth centuries BCE metalwork objects called the Oxus Treasures - artefacts made from gold that date back to the 5th to 4th century BCE.

|

| Gold plaque from Oxus region (Today's Turkmenistan & Uzbekistan) showing a man holding a baresman |

Amongst the artefacts is a gold plaque of a man holding a baresman bundle. The gold plaque and other Oxus treasures are believed to come from the the region of Takht-i Kuwad or Takht-i Sangin in Tajikistan.

[A group of merchants from the Afghanistan/Tajikistan region acquired the Oxus Treasure from an unknown source. The artefacts were subsequently purchased by Capt. F. C. Burton, a British political officer in Afghanistan. The Oxus or Amu Darya river forms the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan before it flows north to the Aral sea. Takht mean throne in Persian, and Takht-i Kuwad lies on the confluence of the Vakhsh and Amu Darya rivers, just west of the Pamir region.]

Nowadays, over two thousand years after the making of the treasurers, the Pamiri people of Tajikistan place bound bundles of stripped willow twigs between the beams in their homes. The bundles are an auspicious harbinger of abundant crops in the new year. Since in spring the willow is the first tree that 'wakes up' after a long sleep - for the Pamiri people, the willow is the symbol of new life.

References to the Baresman

Despite making frequent reference to the baresman, the existing Avesta texts do not explicitly explain the baresman's significance. However, many books of the Avesta have been destroyed and these books could very well have provided more information. We will therefore use the references in the Avesta (Yasna 2 & 25.3, Yasna 57.5, Vendidad 19.18 & 19, Ram Yasht 5.), Pahlavi texts, and Greeks texts to try and understand the purpose and significance of the baresman.

Vendidad 19.18 & 19 directs the practitioner to 'urvaranam uruthmyanam', a growing plant / tree, and to cut baresman twigs of a specified dimension, placing the cut twigs in the left hand. Vendidad 19.19 connects the baresman with haoma described as zairish (golden-green) berezo (exalted / high) in a manner that is not entirely clear in the English translations.

Number of Twigs in the Bundle and Liturgy

|

|

Mah-rui or barsom-dan Ritual baresman stand |

The references in the Avesta and Pahlavi religious texts prescribe the number of twigs to be bundled for different liturgical purposes. The number varies from 35 to 3.

A recitation of the Yasna liturgy requires 23 twigs, 21 of which are tied in a bundle and placed on the mah-rui or barsom-dan, a moon-faced or the crescent-like stand shown on the left. One of the two loose twigs that are not part of the bundle, is placed on the saucer containing the zor or zaothra water. This twig is called the zor-no-tae, meaning the twig of the zor. The saucer and the zor-no-tae twig are placed on the foot of the mah-rui stand the holds the bundle. The second loose twig is placed on a saucer containing the jivam, a mixture of water and milk that will be used in the Yasna ritual (see haoma - the ab-zohr rite).

A recitation of the Vendidad requires 35 twigs, 33 of which are tied in a bundle. The remaining two are placed as above.

For other rituals, the bundle consists of between 3 and 15 twigs.

Material of the Baresman Twigs

Nowadays, the baresman bundle consists of brass or silver strands nine inches long and an eighth of an inch in diameter. All the reference in the Avesta, Pahlavi religious texts and classical Greek texts, however, mention tree and plant twigs as the material of the baresman bundle. The Avesta does not specify a particular tree and the other texts mention different trees whose twigs were used to make the baresman bundle.

Metal rods started to be used after Zoroastrians emigrated to India, where access to the traditional natural materials was probably limited or non-existent in the initial areas where Zoroastrians chose to settle. Dastur Erachji Meherjirana explains this innovation as being "out of helplessness" because the traditional gaz i.e. tamarisk tree was not available in India (Pursesh-Pasakh, 1941, pp. 63-64, cited by Kotwal-Boyd, op cit, pg 68. n 30). In the Persian Rivayats (15-16th century, e.g. Dhabhar, p. 418), the Iranian Zoroastrian priests criticize the Parsis for using the untraditional metal wires.

|

| Barsom / Tamarisk sprigs illustrated in Jackson's book Persia, Past and Present |

Abraham V. Williams Jackson in Chapter 23, The Zoroastrians of Yezd, of his book Persia, Past and Present (1906), states:

"In Yezd the tamarisk bush is used to form this bundle, and it is bound with a slender strip of bark from the mulberry tree, probably in exactly the same manner as it was in Zoroaster’s day. [The Avestan words employed in connection with the baresman indicate that the twigs were originally spread (star-, frastereta-), then gathered into a bundle and hound (yuh-, aiwyasta-, aiwyhana-).] Brass rods are sometimes substituted for the twigs, as is done by the Parsis in India, but at Yezd this substitution is made only in winter, when it is impossible to procure the branches, or at some particular time when it is impracticable to obtain them. ...I saw the large tamarisk bush from which the sprays mere cut for use in the barsom ceremony; it was of a light green color, twelve or fifteen feet high, and stood in the garden adjoining the rear of the temple. A high wall shut in the garden at the back; a gallery ran part of the way around the enclosure; a flight of steep steps led down from this to the ground, where there were blossoming rose bushes, sweet scented shrubs and plants, a pomegranate tree, and the tamarisk bush."

J. J. Modi mentions but does not identify the chini (perhaps the chenar, also spelt chanar or chinar tree. In English: the plane tree) tree as another tree from which the baresman twigs were cut.

Reading the older reference we see that the ability of certain plants to regenerate when cut, combined with their healing and health-giving properties, appear to have made them candidates for inclusion in the baresman bundle as representatives of the vegetable aspect of creation and eternal life.

In ancient times, when average life spans may have been short, living to a ripe old age and dying of natural causes might have been an ideal. Plants that could survive disease, fire, cutting down, and still live for several human generations, could have embodied the concept of immortality. If the plants could have provided healing they could have been viewed as the aegis of health and longevity, if not immortality or eternal life.

In keeping with the Zoroastrian philosophy of existence, there is an duality inherent in nature. While plants can help in healing, consuming them inappropriately can cause great harm.

Greeks and Middle Persian writers and texts mention the different trees or plants whose twigs were used to make up the baresman bundle.

|

| Myrtle |

Myrtle

Strabo writes that the magi "carry on their incantations for a long time, holding in their hands a bundle of slender myrtle wands."

The Pahlavi text, Greater Bundahishn (16.2), mentions the myrtle along with the jasmine as being divine.

In Asia and the Mediterranean, the whole myrtle (Myrtus communis) plant or its different parts, have been macerated in liquids to produce a bitter tea consumed to preserve a youthful appearance, vigour and vitality, including fertility and reproductive vigour. Other uses are the treatment of nervous afflictions, coughs, respiratory infections such as bronchitis, diabetes, and urinary tract disorders.

Myrtle leaves are used to produce aromatic oils with aromatherapy, healing and disinfectant properties.

|

| Myrtle |

Myrtle extracts promote good digestion. They are used to treat inflammation (as an anti-inflammatory), prevent wound infections, promote healing and as a pain reliever (including back pain).

Myrtle also has uses as an astringent and decongestant.

Myrtle makes a excellent firewood, a property that could have made it attractive to the Magi as the fuel for their fires. Myrtle also imparts a spicy, aromatic taste to any meat over which it is grilled.

Myrtle is used in the religious ceremonies of other religions. It was used in ancient Greek rituals where it was used as a symbol of immortality (see Amesha Spenta Amertat above). Wreaths made from myrtle twigs were worn by Greek athletes. In Jewish liturgy, it is one of the four sacred plants of Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles. Three branches are held by the worshippers along with a citron (also called a Median or Persian apple), a palm leaf, and two willow (see below) branches. In Zoroastrian ceremonies, rather than holding a palm leaf with the baresman, the baresman twigs are held together in a bundle with a strip of the date palm leaf called the aiwiyaonghana. These similarities should be kept in context. The magi and their healing abilities as physicians were well known throughout the Middle East. The magi's use of the baresman as an important part of their practice was also probably well known.

|

| True/Grecian/Bay Laurel |

Laurel

Strabo states that the magi also used slender laurel twigs in their rituals.

The laurel plant (Laurus nobilis / Lauraceae) is also called true laurel, true laurel or bay laurel. The laurel leaf, known as a bay leaf, is used to flavour cooking. Under ideal conditions, these laurel plants can grow to six meters in height, though they are commonly found as a two-meter high bush.

The laurel is especially hardy and resilient. It is an evergreen that tolerates heavy pruning and will grow from cuttings - properties that make it a suitable symbol of the Amesha Spenta Amertat.

|

| Laurel Wreath |

As with myrtle, laurel has been used to make laurel wreaths used as a mark of honour or victory in ancient times, for example, to crown the winners of athletic events. The expression "resting on one's laurels" encourages people not to rest with a success, but to continue working. Baccalaureate a bachelor's degree in education comes from laurel berry. Nobel and poet laureate signify the achieving distinction and honour in particular fields.

Again as with the myrtle, extracts of the laurel plant (leaves, fruit, bark and stems) have antioxidant, analgesic (pain relieving), anti-inflammatory and anticonvulsant or antiepileptic (seizure and convulsion controlling) properties. A plaster made from the leaves was used to relieve wasp and bee stings.

The leaf is said to be useful for gastric ulcers, high blood sugar, migraines, and infections. Laurel / bay leaves and berries have been used for their astringent, diaphoretic (promotes sweating), carminative (promotes digestion), digestive, and stomachic (tones and strengthens the stomach) properties. In the Middle Ages, the bay leaf was believed to induce abortions. Traditionally, the berries of the bay tree were used to treat furuncles. The leaf essential oil of Laurus nobilis has been used as an antiepileptic remedy in Iranian traditional medicine.

Dried laurel leaves brewed as an herbal tea is used to treat rheumatism, joint pains, schizophrenia, stress, to stimulate the appetite and as a sedative.

The leaves and fruit of the laurel contain fatty oils and aromatic (essential) oils have special properties and the oil is used extensively in cosmetics and moisturizing products. The oil is also used as a cure for irritated skin, earache, asthma and urinary ailments.

Even today, in Kessab and Kadmus, two Syrian mountain communities, oil is extracted from the berries using age-old processes. Villages collect the berries which are boiled in water for six to eight hours in a metal container over a wood fire. As the oil rises to the surface, it is skimmed off with a wooden spoon then filtered. Sixteen kilograms of laurel berries produce about ten litres of laurel oil. Different varieties of laurel produce oils with different properties.

Soap made from laurel oil has a unique perfume. The soap also nourishes, softens, refreshes, and cleanses skin while acting as an antiseptic. It is especially suited for sensitive skin and to restore damaged skin.

The aromatic laurel leaves ward off insects like earwigs and weevils, and grain can be stored with laurel or bay leaves in order to ward off insects.

The Zoroastrian use of the baresman as a symbol of immortality is echoed in the use of the laurel by Christians to symbolize the resurrection of Christ and thereby eternal life or the triumph of life over death.

Tamarisk

|

| Tamarisk |

Dastur Erachji Meherjirana mentions in (Pursesh-Pasakh, 1941, pp. 63-64, cited by Kotwal-Boyd, op cit, pg 68. n 30) that metal rods were substituted for traditional gaz or tamarisk, because tamarisk was not available in India. Chapter 329 of the Persian Rivayat mention the use of tamarisk and pomegranate trees in the making of the baresman.

The tamarisk, like the plants noted above is a hardy plant and a survivor. Like the laurel, the tamarisk survives heavy pruning by sending up new shoots. The tree can grow to be more than a hundred years old. In addition, since the leaves secrete salt, the plant is very resistant to insect infestations and diseases. All of these characteristics make it another candidate for representing the Amesha Spenta Amertat.

The plant will grow in salty soil and will also out-compete other plants for water in arid conditions.

The tamarisk has medicinal properties very similar to that of the willow described below.

The tamarisk found in Tajikistan is the Tamarix laxa.

Pomegranate

|

| Pomegranate Tree |

The Persian Rivayats mention the tamarisk and the pomegranate are trees from whose branches the baresman was made.

The medicinal qualities of different parts of the pomegranate tree are extensive. Chewing small bits of its bark, petals, and peel can treat ailments from dysentery to diseases of the mouth and gums. The seeds and peel of the fruit are rich in antioxidant tannins and flavonoids.

The dried seeds produce a unique oil, about 80% of which is a very rare 18-carbon fatty acid, punicic acid. Also present in the oil is the isoflavone genistein, the phytoestrogen coumestrol, and the sex steroid estrone. In fact, the pomegranate is one of the only plants in nature known to contain estrone.

Because of role of the pomegranate in the Greek legend of Persephone, the pomegranate came to symbolize fertility, death, and eternity and was an emblem of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Jujube

|

| Jujube Tree |

Jujube sprigs are sometimes used in the Afringan ceremonies in place of myrtle or pomegranate sprigs. The jujube is also called the red date or Chinese date. The plant is found as a bush or as a tree, five to ten metres in height. Wild jujube can be very thorny.

Nowadays, it is the fruit that is primarily used for health and curative purposes. They are reputed to relieve stress, pain and sore throats. They also reduce water retention by the body. In China, wild jujube fruit is consumed to improve general health. The common belief is that if the fruit is consumed on a daily basis, it will help improve skin color and tone, both signs of physical well being. The cultivated plant's fruit is said to cool the body and treats the cause of sleeplessness and mental fatigue. It is claimed to combat wasting disease and restore a body ravaged by illness.

Jujube pits, when aged for three years, are considered excellent for wounds and abdominal pain.

The leaves are used in a potpourri as a room deodorant, an insect repellent, and insecticide. The leaves or tea when consumed are said to kill intestinal parasites and worms which cause diarrhoea. It has also been used to treat children suffering from typhoid fever. In Haiti, a tea of the leaves and fruit is consumed as an antidote to poison.

The heartwood is considered a powerful blood tonic and the bark has been used to make an eye wash for inflamed eyes.

Willow

|

| Common willow |

In Tajikistan, there is an interesting tradition where in preparation of Nowruz (New Year's day) festivities, freshly stripped willow twigs are bundled together and placed in homes. Since in spring the willow is the first tree to 'wakes up' after a long sleep, for the Pamiri people in Tajikistan, the willow is the symbol of new life.

The willow has many symbolic and medicinal uses. It has been used to treat headaches, fever, gout, arthritis, and pain. It is particularly effective for lower back pain. Individuals can chew on the bark to reduce fever and inflammation, or a decoction of the bark of the shoots and the roots can be made to treat jaundice, rheumatism, venereal disease and fever. Today we understand that the willow bark is a source of salicin whose modern isolation lead to the synthesis of acetyl salicylic acid (ASA), the main component of aspirin.

Willow extract is used as a disinfectant and as an antiseptic. To make the extract, young willow shoots are boiled in water to extract the water soluble medicinal substances and the extract is used as a wash for abscesses, ulcers and skin diseases.

Different parts of the tree can be used in different ways. The shoots are used to treat measles. The gum from the plant and the down of seeds are prescribed for sores. The thin long twigs are used for treating rheumatism and gonorrhoea.

Juniper

|

| Ziarat Juniper Forest in Baluchistan, Pakistan |

Juniper wood is used in Zoroastrian ceremonies in Iran and the tree is considered sacred in Tajikistan. The smoke of the juniper has healing and disinfectant properties. The juniper could very well have been used for religious ceremonies in the same way that sandalwood was used by Zoroastrians in India. The uses of juniper go beyond burning the wood. The extract is considered healing and the berries are used as food.

Unlike the other plants noted above, the juniper (Juniperus communis / family: Cupressaceae the cypress family) is a conifer. There are juniper forests throughout Central Asia and into present-day Pakistan. Some of the trees in these forests are reputed to be 5,000 years old - making the juniper and the cypress suitable representatives of the Amesha Spenta Amertat.

There is an interesting study available online titled Antioxidant Activity of Leaves and Fruits of Iranian Conifers, that includes the juniper.

Juniper has diuretic, antiseptic, stomachic, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-rheumatic properties, and has traditionally been used as a remedy for cancer, digestive problems such as gas, belching, heartburn and dyspepsia (indigestion), warts, bronchitis, tuberculosis, colic, heart failure, intestinal disease, gout, and back pain. The berries were often eaten to relieve rheumatism and even freshen bad breath. Chewing juniper berries helps to prevent getting or spreading infection, especially when providing health care.

In addition, juniper has been used to treat bladder infections, kidney disease, gallstones, fluid retention, cystitis, inflammation, and high blood pressure.

|

| Berries on Juniperus Communis |

The tree's therapeutic properties stem from a volatile oil found in the berries. This oil contains terpenes, flavonoid glycosides, tannins, sugar, tar, and resin. Terpinen-4-ol (a diuretic compound of the oil) stimulates the kidneys, increasing their filtration rate. The flavonoid amentoflavone exhibits antiviral properties. Test tube studies show that another constituent of juniper, desoxypodophyllotoxins, may act to inhibit the herpes simplex virus. The resins and tars contained in the oil benefit such skin conditions as psoriasis. The oil also acts as a laxative.

When consumed, Juniper berries act as a strong urinary tract disinfectant. Amongst their varied uses, the berries have been used to assist childbirth and promote menstruation during menstrual irregularities.

The berries and leaves have been used to treat infections, arthritis, and wounds.

A tea made from juniper berries and berberis (the dried berries of which are called zereshk in Iran) root bark is used to treat insulin-dependent diabetes. Compounds in these plants have been shown to trigger insulin production in the bodies fat cells, and they stabilize blood sugar levels as well.

Dioscorides' De materia medica states that crushed juniper berries placed on the penis or vagina before intercourse, acts as a contraceptive.

Juniper berries though very bitter are crushed and used sparingly to flavour meat. The word gin comes from the French word for juniper berry, geničvre, the name for gin in France.

The juniper is considered a sacred tree in Tajikistan. The principle juniper trees in Tajikistan's forests today are Juniperus semiglobosa (Turkistan mountain ridges), Juniperus turkestanica and Juniperus seravschanica (Zeravshan and Gissar mountain ridges).

Regrettably, the juniper, that populated many of the lower slopes of the Iranian and Central Asian mountain slopes, have now, because of indiscriminate felling in the last fifty years, retreated to the upper inaccessible slopes, probably, with a loss of certain species. Almost all these environs were covered by the Persian Juniper Juniperus polycarpus and the area of these juniper forests was estimated at around 3.4 million hectares just 50 years ago with a biomass of 30 tonnes/hectare. Currently the most optimistic figures are 500,000 hectares, with a biomass of 5 tonnes/hectare.

Chenar or Plane Tree

|

| Legendary Chenar Tree in Urgut, Zerafshan Valley, Uzbekistan |

J. J. Modi mentions the use of chini tree twigs as a material for the baresman in his book The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of the Parsees, Bombay, 1922, p. 277. "The twigs of a particular tree used in liturgical ceremonies are spoken of as the barsom. Later books say that the twigs may be of the pomegranate tree or of the tree known as the chini."

Since we can find no references to a chini tree in Iran, Modi could have meant to say the chenar tree, for the chenar tree (the oriental plane tree - Platanus orientalis L., fam. Platanaceae) together with the cypress (sarv) tree, have long been considered to be sacred trees in Iran. Both are associated with longevity and therefore likely candidates as symbols for the ideal of Amertat (immortality). 2,000 year-old chenar trees are reported to exist, while a sarv or cypress tree in Yazd is reported to be 4,000 to 4,500 years old.

Older trees develop hollow trunks that have been used as rooms and shrines. Licinius Mucianus (1st century CE), the Roman consul to Lycia, is said to have dined within a chenar hollow trunk together with eighteen other people who were part of his retinue.

The habitat of the plane tree extends from south-eastern Europe to Kashmir and Central Asia. It is, however, especially common and popular in Iran. A number of Iranian towns, villages and locations use chenar in their names - for instance Chenarestan, a village near Qazvin.

Plane tree wood is a light hardwood that has been used for columns, doors and furniture. The name plane may have come from the easy with which the wood can be planed and smoothened.

The dry wood of the plane tree is the kind of wood needed in starting a fire by rubbing together two pieces of wood. The dry wood is so combustible, that dry plane trees are known to have spontaneously burst into flame.

|

| Chenar / Plane Trees lining Zafaranieh Avenue next to Saadabad Palace, Tehran, Iran |

Plane trees are widely used in Iran as shade trees to line city streets, boulevards and gardens. Young chenars grow rapidly to reach heights

of 30 metres or 100 feet with a spreading crown. While they grow well in cool, moist soils, they are resilient and can grow in dry, clay-like soils as well.

Contributing to the chenar's popularity is its ability to tolerate urban pollution - both air and water borne pollution. In addition, the chenar is reported to help clean the air of pollutants.

In the Mediterranean island of Kos stands the plane tree of Hippocrates (c 460 BCE - c 370 BCE, the reputed father of western medicine), and under whose shade, Hippocrates is said to have taught his students. However, the tree is around 600 years old and while not old enough to have been the tree of Hippocrates, the myth surrounding the tree has interesting implications including the chenar's association with healing. For that association we need to look further east and it is not without significance that the chenar is called the oriental plane tree.

In ancient Persia, the chenar tree's components have reputedly been used to stop the spread of infection and air-borne diseases. It is possible that smoke from burning twigs of the chenar tree were used by the ancients to disinfect a room or home especially when tending to the sick - in much the same way they could have used juniper wood.

The bruised fresh leaves reportedly can be placed on the eyes in the treatment of eye problems and infections.

Leaf extracts and creams have been used to reduce inflammation, stop bleeding and heal wounds including chilblains. Bark extracts have been used to treat hernias.

Leaf extracts and bark extracts (using vinegar) have been used to treat dysentery and diarrhoea.

The bark extracts was used to reduce toothache and gum inflammation. The extracts are also reported to have been used to treat asthma.

The fruit of the plane tree was soaked in wine and the extract was used to treat snake bites and scorpion stings.

While we do not have any information about the medicinal uses of the extracts from crushed twigs, we understand that some varieties of the tree produce a drinkable sap.

Camel Thorn

|

| Camel-Thorn Bush (Alhagi maurorum) |

[Note: the camel-thorn bush (Alhagi maurorum, family Leguminosae) is different from the Camel Thorn tree fond in Southern Africa.]

Camel-thorn, Kar shutur in Persian, has been widely used in Iranian folk medicine to treat gastric disturbances, as a laxative, expectorant, and to reduce gastric acidity. The dried vegetation has been collected in the winter months preceding Jashne Sadeh for temple fires. In Azerbaijan, the dried plant is hung on the inside of the front door to combat the evil eye.

Camels like to eat the bush giving the plant its name. The plant is fed to dairy animals to increase milk production.

The camel-thorn (or camelthorn) bush is found throughout the sixteen Vendidad Aryan nations. The visible bush, about a meter in height, is a perennial that grows from a massive rhizome system that can extends to a depth of two meters, and which send up new shoots as far as seven meters from the parent plant.

|

| Close up of a Camel-Thorn branch |

The bush is heavily-branched with gray-green foliage and long spines. The flowers and fruit are legume-like. The flowers are small bright pink to maroon in colour. The seed (pea-like) pods are brown or reddish. The seeds are mottled brown beans.

The plant's sap contains mannitol, a sugar alcohol, which is a diuretic (increases urination), a weak kidney vasodilator (widens vessels) and helps reduce acutely raised intracranial pressure. It is also used as a treatment for cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. Mannitol is also the drug of choice for the treatment of acute glaucoma in veterinary medicine.

The secretion of camel-thorn is sometime called called 'manna' (since it resembles a Biblical food), mannite or manna sugar. It key ingredient, mannitol is also used as a sweetener for people with diabetes. The exudation dries to white grains and can be shaken off the branches. It addition to is health related uses, the manna is also used in the preparation of sweetmeats.

Gaz / Shir Khoshk / Manna

Camel-thorn is one of the four varieties of plants in Iran that yield 'manna'. The other three are: Cotoneaster nummularia known as shir khisht in Persian (shir means milk and khoshk means dry), gaz-anjabin (Tamarix gallica L.), and shakar tiqal (meaning sugar of nests), the product not of the plant, but of a beetle that lives on the plant Echinops persicus. The dried sap is eaten in its natural state, made into a sweetmeat or mixed with water. We include the plant sources here since the sap is a form of extract from the living branch.

Gaz is a popular sweetmeat that originated in Isfahan, Iran. It is made into a nougat using the sweet milky sap of the anjabin plant as the base to which ingredients including pistachio or almond kernels, egg whites and rose water are added. Anjabin is a member of the Tamarisk family and native to the arid regions of Zagros mountain range located to the west of Isfahan.

Shir khisht, meaning dried milk, is a common shrub on the Sia-Koh and Safed-Koh ranges, growing at an elevation of 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) and higher. The properties of its white, sugary lumps of 'manna' which it yields from its smaller branches in certain seasons, are similar to desert-thorn. Mixed with water, the 'manna' is considered a remedy for typhoid.

Shakar tiqal, meaning sugar of nests, is a sweet substance formed the cocoons of a beetle (Larinus maculatus) that lives on the leaves and stalks of the plant species of echinops. The insect forms a rough, rounded-oval, chalky-looking cocoon, 18 to 20 mm. long. The cocoon contains 15 to 23 per cent of mycose sugar, a secretion that was described in Pharmacopoeia Persica (1681 CE and credited to Fr. Angelus - the first European to make a study of persian Medicine), as a remedy for coughs and to relieve breathing problems.

Date Palm

The leaves of the date palm are cut into strips, braided and used to tie the baresman bundle together (aiwiyaonghan / aiwyaonghana) during the Yasna ceremony. It is not clear if the stems of the leaves or if the date fruit were used for medicinal purposes, though it is likely that the medical properties were investigated and that the fruit was consumed fresh and dried as a part of the dried foods distributed during the gahambar / gahanbar festivals. The health benefits of the date fruit are well known.

The more we have researched the healing practices of the ancient Aryans, the more we have come to realize that we have probably lost more information that can be gleaned from all the sources available to us today.

A Word of Caution

All the healing information on this page needs to be used with extreme caution as plant extracts of any kind can be harmful, poisonous or fatal if consumed incorrectly.

Connections Baresman and Haoma

In Zoroastrian scripture and practice baresman is closely linked to the healing plant or plant family haoma.

» Top