Contents

Darband / Derbent

x

Suggested prior reading:

» Caucasia

» Azerbaijan

Related reading:

» Surakhani, Azerbaijan, Atashgah

» Khinalig, Azerbaijan, Atashgah

Darband/Derbent - Background

|

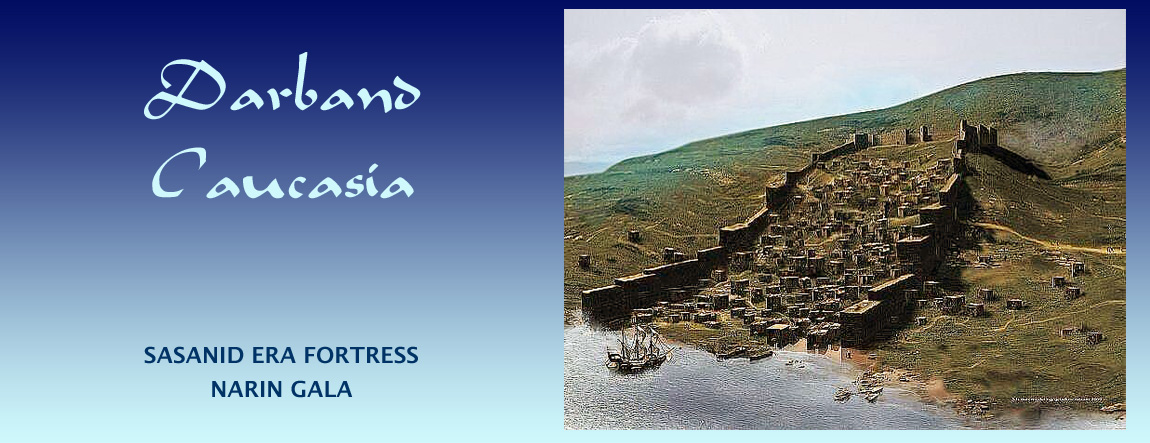

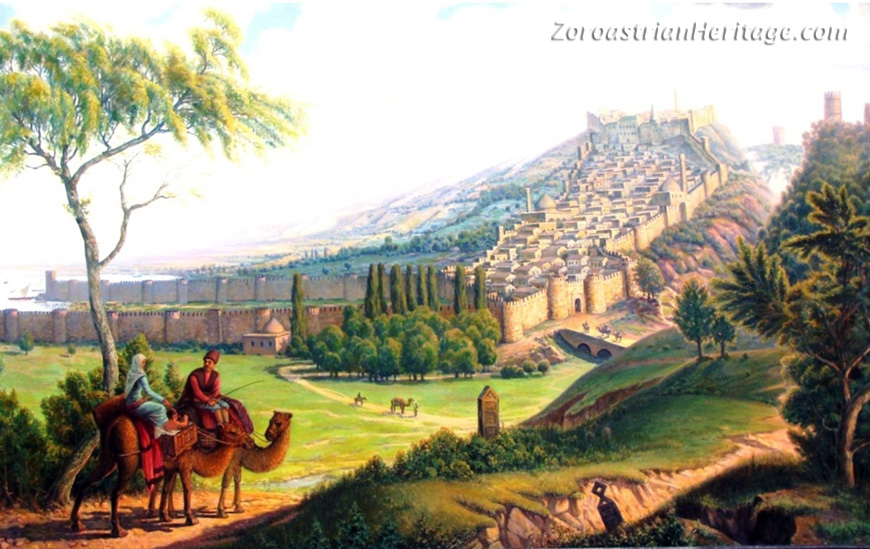

| An artist's impression of Darband & in medieval times. Image credit: Musa Musayev. |

The city of Darband/Derbent - now a town in the Russian Republic of Dagestan - was a northern frontier border town during Aryan-Zoroastrian rule of the region. 'Darband' means 'closed door' or 'closed gate' in Persian. It is commonly reported that the name and its meaning refer to Darband's strategic placement that enabled its fort's garrisons to stop marauding northern tribes from raiding Aryan lands to the south. There is a fort in the city built by the Sasanids, say, in the mid-5th century CE. In our page on Caucasia, we noted that according to one theory, Darband was likely part of the Sasanid province of Balasagan.

An 1886 census recorded that ethnic Iranians made up about 60% of Darband's population (see Tati-Parsi in our Darband page).

Eventually, Darband did succumb to a northern invasion, this time by the armies of the Russian Empire. After intermittent periods of Russian occupation starting in 1723, the city among with the province of Dagestan were ceded to Russia after Russia defeated Qajar Iran in the Russo-Persian War of 1804-1813.

|

| East Caucasus region map with locations of some old Atashgahs & historic sites. Image credit: Base map - Encarta. Modifications - K. E. Eduljee |

Narrow Pass

Darband is located on a narrow 3 km (2 mi) wide stretch of relatively flat land between the Great Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea. It is located on the narrowest portion of the coastal land which widens somewhat to the north and south of the city.

Surrounding mountains made the narrow passage the only feasible regional route for caravans to ply their trade. One branch of the Aryan trade road would have run right behind the town's fort.

Strategic Importance & Position

In our page on Caucasia, we had noted that according to one interpretation of an inscription, the last Zoroastrian dynasty to rule Aryana/Iran-shahr, the Zoroastrian Sasanids (c.225-645 CE), called the frontier province at the junction of the Great Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea, Balasagan/Balasakan. One transcription of the inscription of King Shapur I (r. 241-272 CE) at Naqsh-e Rustam reads, "Balasagan ta fraz o Kaf-Kof ud Alanan bar/dar" meaning 'Balasagan up to the Caucasus Mts. and the Gate of the Alans'. The Gate of Alans may have been the city and its fortifications now called Derbent or Darband meaning 'closed-door' referring to a closed pass.

According to Erich Kettenhofen in 'Darband' at Iranica, "Neither Albania [the Greco-Roman name for Aran/Ardan] nor the city of Darband seems to have been conquered by the Romans in their struggle with the Parthians for hegemony in the Caucasus; nor, despite claims in the Armenian sources, is Armenian influence recognizable in the region. Coins and architectural details are evidence of interaction with the Parthians...." "As attacks by northern peoples [Huns at the end of the 4th cent. CE] became more frequent, Darband came to be the most important bastion and the symbolic boundary between the nomadic and agrarian ways of life."

Age of Darband: c. 5,000 Years Old

According to Erich Kettenhofen, "Owing to excavations conducted by Soviet archeologists beginning in 1971, the history of Darband can be traced back as far as the late 4th millennium BCE. Finds of stone and bronze axes and pottery suggest that the peak of the hill was settled by then."

Eight Century BCE Fortifications & Early History

Erich Kettenhofen at Iranica: "In the 1st millennium BCE, the history of Darband was closely linked to events north of the Caucasus and on the Eurasian steppes in general, and the fortress was important in the defence of areas south of the Caucasus." "...The initial fortification of the hill at the end of the 8th century BCE. appears to have been a response by the indigenous population to Scythian invasions from the north." "The walls apparently attained a maximum height of 2 m and a maximum thickness of 7 m. The fortress seems to have been destroyed repeatedly during this [4-5 cent.CE] and the following periods."

At the beginning of the 4th cent. BCE, the hill became the citadel of an expanding city.

Darband's Sasanid Fortress Narin Gala/Naryn Kala

|

| An artist's impression of medieval Narin Gala/Naryn Kala with its lower wall extensions intact. The town and its harbour were protected by high walls. Image credit: Artist unknown |

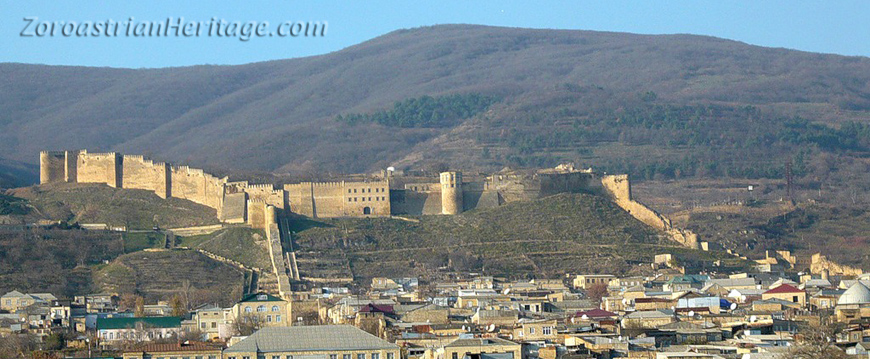

Darban's Sasanid Fortress Narin Gala (Naryn Kala) was placed on UNESCO's World Heritage List in 2003. According to UNESCO.ru and UNESCO.org, in the mid-5th century CE (during the Sasanid era), Derbent received its present name and its most spectacular feature - the twin parallel stone walls stretching from the mountains to the sea. The walls are 12 meters high on the average, three meters wide, and are separated by 300 to 400 meters. They even stretch some 500 meters into the Caspian Sea. The oldest part of the city is situated between the two walls. Eric A. Powell in 'The Shah's Great Wall', states, that the walls attached to the fortress are "known locally as Dag Bahri, the mountain wall."

Originally the walls had 73 towers, but the southern towers were partially dismantled in the 19th century. Now, only 46 towers remain. The fortifications also had 14 gates, but only nine of them still exist. The walls extend uphill to the still standing Narin-Kala fortress built on the highest point of the hill.

|

| Darband's Sasanid Fortress Narin Gala/Naryn Kala - view from the Caspian Sea direction. Image credit: ajanskafkas.com |

|

| Darband's Sasanid Fortress Narin Gala/Naryn Kala - an aerial view. Image credit: elevation.maplogs.com. |

Narin Gala/Naryn Kala's Pahlavi Inscription

|

| Middle Persian (Pahlavi) inscription on the Darband's wall. Image credit: Bahman Sarjani via Farroukh Jorat. |

Farroukh Jorat in his paper 'Zoroastrianism in Northern Shirvan' notes that there are more than ten inscriptions on Narin Gala's walls written in Middle Persian/Pahlavi. The transliteration of one reads, "ZNE W MN ZNE ’plbl dlywš ZY ’twrp’tkn ’m’lkl". It transcribes as, "ēn ud az ēn ābarbar Daryuš ī Ādurbādagān āmārgar", and translates as "This and higher than this made by Dariush, revenue/tax collector of Adurbadagan (Azerbaijan)". [from, Jorat, Farroukh - 'Zoroastrianism in Northern Shirvan']

Zoroastrianism in Derbent & Dagestan

F. Jorat also notes a passage from the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) inscription of 3rd century Magupaiti (Mobed and Head Priest of Iran) Kartir, found on the walls of the so-called Kaba-e Zarthosht at Naqsh-e Rostam. Our translation is as follows: "...By the command of the King of Kings, I (Magupaiti Kartir) instituted Mobeds (Zoroastrian priests) and fires in countries outside Iran ...(including) Arman (Armenia), Virzan (Iberia) and Aran/Ardan (Albania) as well as from Balasagan up to the Caucasus Mts. and the Gate of the Alans." It is noteworthy that these nations were listed as part of Aniran - outside Iran - and not part of Iran-Shahr proper which ended at Azerbaijan.

Jorat goes on to state, that interesting information about Zoroastrianism in Darband as late as the 19th century CE is given by D. Shapiro in 'A Karaite from Wolhynia meets a Zoroastrian from Baku'*. Avraham Firkowicz, a Jewish Karaite and collector of ancient manuscripts, wrote about a 1840 meeting with a "fire-worshipper" in Darband. Firkowicz asked the man, "Why do you worship fire?" To which the man replied that he does not worship fire, but rather the Creator symbolized by fire called Q’rţ’, an abstraction and hence not a person. The Pahlavi word Q’rţ’ is derived from Avestan kirdar signifying the Creator. [*Dan Shapira in 'A Karaite from Wolhynia Meets a Zoroastrian from Baku', Vol. 5, No. 1, 2001, pp. 105-106.]

Yetti Goilar Gorge & Cave - a Dakhma?

|

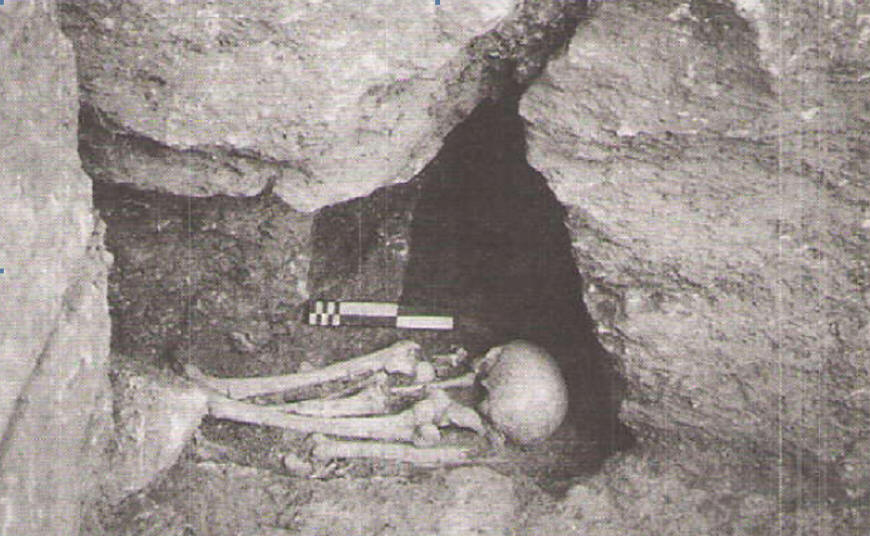

| Zoroastrian funerary complex. In the foreground, the "House of the Dead". In the background, the dakhma's entrance in the cave. Image credit: Murtazali Gadjiev via Farroukh Jorat. |

F. Jorat in 'Zoroastrianism in Northern Shirvan' (edited for syntax) quoting Dr. Murtazali Gadjiev's Zoroastrian Funeral Complex near Derbent states, "In 2000, on the slopes of the gorge "Yetti goilar", a small cave (depth 1.7 m, width 3.6 m, height 1.8 m) attracted the attention of Derbent archaeologists. An inspection led to the theory that the cave was a type of dakhma, a Zoroastrian structure for placement of corpse to prevent defilement of the soil. The dried bones of the skeleton were then placed in an astodan, a small ossuary.

"A partition isolated the bodily remains from the rest of the room for the yashti-sedush and shab-girih ceremony. In the corner of the room, next to the first burial, in a small niche in the rock, an ossuary (astodan) was found with a neatly stacked complete skeleton of a man. Bricks in the cave have been dated to the 13 to 15 century CE.

Jorat also provides a quote attributed to 9th century writer al-Masudi in M. M. Mammayev's 'Zoroastrianism in Medieval Daghestan': "When anyone of them dies, they put the corpse on a stretcher and carry it to the open place ("maidan"), where it is left for three days on a stretcher ... This practice had been common among residents of this city (Darband - F. J.) for 300 years.... On the fourth day the they placed the remains in the rock tombs or in stone boxes (astodan)."

|

| The astodan (ossuary). Image credit: Murtazali Gadjiev via Farroukh Jorat. |