Contents

|

Further reading:

Shanidar Cave - Location & Discovery

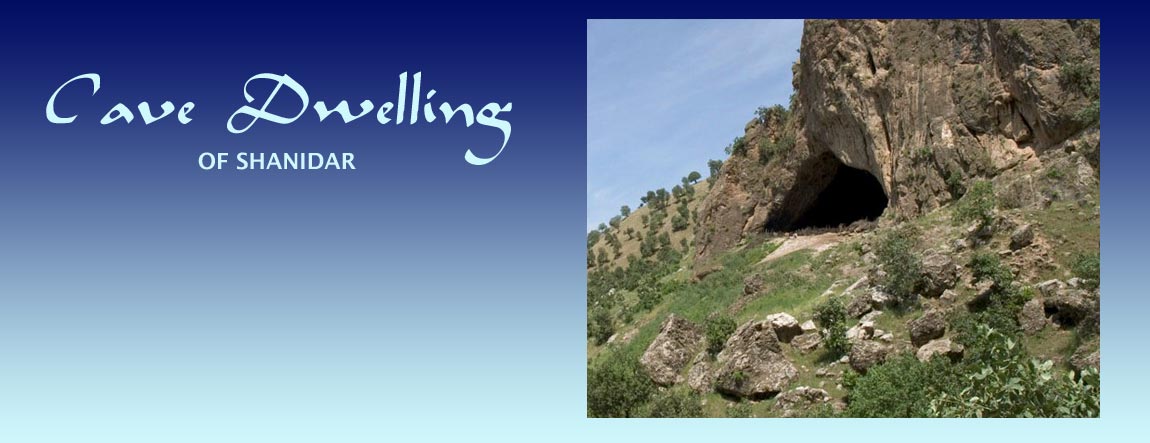

Known locally as Shkaft Mazin Shanidar (Cave Big Shanidar), Shanidar Cave in Kurdistan, northern Iraq, has yielded evidence of the earliest known cave dwelling community in the region of Aryana.

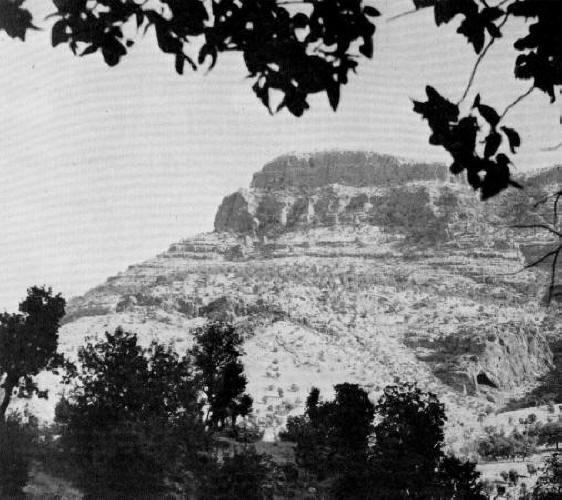

The cave lies about 130 km west of the southern tip of Iran's Lake Urmia and about four km upstream from the village of Zawi Chemi Shanidar. It burrows into the side of Baradost Mountain at an elevation of 747 m. Baradost Mountain is a long craggy western spur of the Zagros Mountains and the valleys around it are famed for their rugged beauty.

The village of Zawi Chemi Shanidar sits on the banks of the Greater Zab River. The Greater Zab River is a significant Tigris River tributary and one that features in the history of Greater Aryana.

Shanidar Cave was discovered in 1951 by Ralph Solecki during an archaeological survey of prehistoric caves in the Rowanduz/Rawanduz area that was part of the

Erbil Governorate of Iraqi Kurdistan. The town of Rowanduz/Rawanduz is about 50 km west of the Iranian border and like Shanidar, lies among western spurs of the northern Zagros mountains.

corrals.

Solecki, who was accompanied on his survey by the district governor (qaimakan) and a representative of the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities, recorded and examined about forty caves and shelters. Among these, Solecki identified Shanidar Cave as the one most likely to yield new evidence of prehistoric development in the area. At that time, the cave seemed to be unoccupied other than containing a few temporary huts and some animal corrals.

|

Greater Zab Valley map showing Shanidar location. Image credit::

Ralph Solecki in Shanidar, the First Flower People (1971)

and as posted on Don's Maps |

|

Discovery that Shanidar was Home to Neanderthals

Between 1953 and 1961, an archaeological team led by Smithsonian anthropologist Ralph Solecki discovered remains and artifacts that indicated Shanidar Cave had been inhabited by a small community of Neanderthals nearly 70,000 years ago. The cave continued to be seasonally inhabited by local shepherds at the time of Solecki's visit.

|

| Ridge of Baradost Mountain and the cave mouth. Image credit: Ralph Solecki |

|

| Shanidar cave mouth |

|

Shanidar's Neanderthal Occupants & the Cradle of Civilization

Neanderthals or Neanderthals are an extinct species of human-like primates. The first proto-Neanderthals are believed to have existed as early as 600,000 to 350,000 years ago. They may have become extinct about 30,000 years ago though not before they intermingled with Homo sapiens, the primates who were the fore-runners of modern-day humans. The skeletal remains of Shanidar's Neanderthal residents extend from about 80,000 to 45,000 years ago. Solecki estimated "that the cave could have housed at least six families, perhaps more, of at least seventy to eighty people."

According to the Smithsonian, the findings of their archaeological team changed anthropologists' understanding of the Neanderthals. As a result of the Shanidar findings, anthropologists concluded that the human family's advance towards civilization had started much earlier than been previously assumed. Prior to the discovery of the Shanidar Neanderthals, it was thought that Neanderthals - such as those first discovered in 1856 by workers at a limestone quarry in the Neander Valley (Thal) near Düsseldorf, Germany - may have resembled apes rather than modern humans both in posture, intelligence and group interactions. The Shanidar discovery changed that thinking completely.

Further, this advance in early human development had taken place in an area not commonly recognized as a cradle of civilization. (Also see our page on Anau and Raphael Pumpelly. The entire band from the Upper Tigris region to Central Asia merits more research into its contributions to the development of civilization.)

Ralph Solecki in his Shanidar, the First Flower People (1971), states "I took special pains to save the charcoal from the hearths in Layers B, C, and D." The interface between levels C & D, i.e. 35,000 years ago, was where the skeletal remains of the Neanderthal 'Shanidar I' was found. If correct, then the Neanderthal residents of Shanidar Cave either knew how to make fire or they knew how to maintain naturally generated fire. Solecki team began to call Shanidar I, 'Nandy'. 'Nandy' appears to have been born with a deformity on the right side of his body leaving his right arm useless (and amputated just above the elbow) He was blind in the left eye and afflicted by arthritis (a rather common ailment among Neanderthals). It is very doubtful if 'Nandy' could have foraged for food or joined in any hunting. Yet he lived to a ripe 'old' age of about forty - forty was the Neanderthal equivalent of our eighty years of age - before being killed by falling rocks from the cave's ceiling. The surviving residents covered his body with soil and rocks, thus burying him 'in-situ'. Solecki notes, "That 'Nandy' made himself useful around the hearth (two hearths were found very close to him) is evidenced by the unusual wear on his front teeth. It presumably indicates that in lieu of a right arm, he used his jaws for grasping, while manipulating with his good left arm and hand. The stones over his remains, and the mammal food remains, show that even in death his person was an object of some esteem, if not respect, born out of close association against a hostile outside." In the relatively small area of the initial trench dug by Solecki's team, while the uncovered remains of 'Nandy' and three others indicate that they were killed and buried or pinned by rock-falls from the ceiling (likely caused by earthquakes), four others were intentionally buried in that area.

In conclusion, the Neanderthal residents of the cave existed as a small mutually supportive community. In all likelihood, they cared for their injured and infirm. They gathered and ate around hearth fires. Rather than burying or disposing of their dead outside the cave, the cave's occupants buried their dead within the cave itself. The method of burial in the Shanidar Caves indicated a possible belief in an afterlife, perhaps even an understanding of the health properties of plants, and socialization skills.

'Nandy's' death by a rock-fall was followed by yet another rock-fall which, Solecki writes, "sealed off the Mousterian (flint for tools) deposit in this quarter. Thus ended a people and an age at Shanidar Cave."

Shanidar's Modern Occupants

When Solecki began his excavations, Shanidar Cave was being used as a seasonal dwelling by several goatherd families of about forty-five Sherwani Kurds (in Persian, Shervan means people or protector of lions. The ending -van has Avestan roots). The Kurds and their animals moved in annually during the late fall and winter months to spend the cold season in the cave. Their seasonal dwellings places were towards the walls of the cave. This use of the cave by its modern inhabitants prompted Solecki to speculate that in ancient times the prehistoric inhabitants of the cave followed the same pattern, namely, favouring habitation along the interior walls of the cave while leaving the centre and front clear.

Solecki notes, "We learned that the cave was partitioned off into ownerships, and that six families had an interest in the cave. one of our rock-breaker families' share was destined to become the bottom of the (excavation) pit. The cave was once owned, according to tradition, by Khuder Agha from a village called Korka near Mergasur (Mergasur is the name of a village and the valley across the Baradost Mountain to the north-north-east of Shanidar Cave)). The wily Khor Pasha of Rowanduz was supposed to have taken refuge here with his army. The Turks, met him in battle in this area. They blasted into the cave with cannon, and the men of Khor Pasha fought back with flintlock rifles. Indeed, this was not the last time that the cave had been used as a refuge. Hinting at a more recent cannonade was the discovery of fragments of artillery shells in the excavations. There was some corroboration, for a few chunks of stone had recently become dislodged from the ceiling, as indicated by the bare, white patches in the soot-blackened expanse. There was a tar deposit about one-sixteenth of an inch thick on some of the stones. The tar or blackened discolouration had seeped into the cracks on one sample to a depth of about three quarters of an inch. The whole ceiling was covered with a hard shiny substance, which I presumed to be sinter, or limestone percolation." Further, "Corporal Lazar told me that the people of Mergasur, who were returning to live at Shanidar, had no caves in the Mergasur valley. There were five of six caves in the Shanidar valley which were occupied by the Mergasuri people during the winter months. At the first break of spring they went back to their more open homes (in the meadows while their animals grazed)."

|

| Cave mouth from the inside. Image credit: James Gordon at Flickr |

|

| Cave interior |

|

Shanidar Cave Description, Excavations & Datings

|

| Cave plan during Solecki's excavation showing the first trench at the centre-front of the cave |

|

Cross section of the first trench. The large stone is from one of at least nine major rock-falls

from the cave's ceiling during the Middle Paleolithic age, covering a span of an

estimated 40,000 years, from 80,000 to 40,000 years ago. |

The floor area of Shanidar Cave is about 1086 sq.m. It's relatively high ceiling - 14 m from the floor at it highest point - is blackened by the soot of fires through the ages. According to Solecki, "Not far from the opening the width increases abruptly towards the interior to an extreme of 175 feet. The ceiling vaults loftily to a jagged crevice about 45 feet from the cave floor. From this point inwards the ceiling falls away rapidly to a height of 25 feet, then gradually slopes to the rear until the end of the cave is met, some 130 feet from the cave mouth."

Given that there were brush houses and livestock corrals along the interior walls and the rear of the cave area, that were still being used by shepherds in the winter, Ralph Solecki's excavations began with a trench in the open central-southern portion near the mouth of the cave. This excavation involved digging a deep trench that had a surface area of about 136 sq.m.

Solecki's excavations at the Shanidar cave extended over a period of four 'seasons': 1951, 1953, 1956-57 and 1960. During the final two seasons, Solecki also excavated an at the back of the cave (the north end). Explorations ceased in 1961 due to the deteriorating political climate.

According to Solecki, Four major cultural horizons (periods) were identified in the 14 m (45 ft) deep excavation pit. From the top of the pit to the bottom, these are: Layer A (recent to c. 4,000 yrs BP), [the time interval between the base of layer A and the top of layer B1 was about 6,000 years. Layer B1 (Proto-Neolithic c. 10,600 BP in 1958 ± 300 years) and B2 (Zarzian or Epipaleolithic/Mesolithic 12,000 BP/10,450 BCE ± 400 years), Layer C (Baradostian or Upper Paleolithic: 28,700-35,100 BP) and Layer D (Zagros Mousterian or Middle Paleolithic: 35,100 to 100,000 BP). [We find there is no consistency between authors regarding the duration of the periods. Paleolithic means Old Stone Age.]

Layer A was a very dense occupational zone that included many bands of large and varicoloured hearth lenses with inclusion of animal bones, potsherds, and a great quantity of goat and sheep dung in its upper parts. There is also evidence of wide spread burning of animal dung.

Layer D had the longest occupation and extended down to bedrock. It is in Layer D that nine skeletal remains were recovered. The remains of a tenth individuals were identified later. The team dated the remains to the last Ice Age - 65,000 to 35,000 years ago. Proto-Neolithic skeletal remains were also found in the back of the cave during the 1960 excavation season (see below).

Most of the individuals whose remains were discovered had been intentionally buried. However, three of the individuals appear to have been killed by rock-falls from the cave's ceiling. It is significant that the burials took place within the cave itself and that the bodies were not buried or disposed of outside the cave.

Solecki notes, "One of the rockfalls killed Shanidar I and V (found at about 4.3 to 4.4 m.). This rockfall appears to have been the result of a massive ceiling collapse. The probable timing of this rockfall was somewhere between 50,000 to 45,000 years ago, from the carbon 14 dating." Further, "The rockfalls were due to structural weaknesses of the limestone, undoubtedly hastened by freezing and thawing annually, and by the ever present danger of earthquakes. The cave lies near a fault line. It appears that the stone age occupants modified some of the floor area for their living convenience, moving stone blocks and on occasion levelling the floor with earth. One cleared floor area measured 4 x 6 m, and included six hearths."

Even though the skeletal remains of the cave's older inhabitants indicate that they lived lived to about 40 to 50 years of age (Shanidar 1, 3, 4, and 5), the skeletons should a high degree of wear and tear. All four remains showed a complete wearing away of the crowns of their front teeth to the extent that the individuals' front roots had begun to serve as chewing surfaces. Further, all four of these older Shanidar males exhibit healed traumatic injuries. The remains of Shanidar 1 showed injuries to the forehead, face, and right arm, leg, and foot. He had apparently survived for years without the use of one arm and was blind in one eye as well. All in all the skeletal remains show that Shanidar's Neanderthal occupants led a difficult, dangerous, and stressful existence. Nevertheless, they appear to have cared for one another for without this care, severely injured and infirm members of the group would not have been able to survive till - what was then - a ripe old age.

Proto-Neolithic Cemetery

[Proto means first in time, the earliest. Neolithic means New Stone Age, the latest period of the Stone Age, commonly placed between about 8,000 and 5,000 BCE, and characterized by the beginnings of settled agriculture and the use of polished stone tools and weapons. The name 'Proto-Neolithic' would denote the earliest Neolithic inhabitants. The Proto-Neolithic period is commonly thought to extend from 10,200 and 8,800 BCE though Shanidar's Proto-Neolithic occupants appear to have preceded 10,200 BCE.]

At the time of the original excavation, the only clear area in the cave was the central part and the front. Structures blocked access to the rear of the cave. In 1960, the rear of the cave became available for exploration.

A Proto-Neolithic cemetery dating circa 10,600 years BP (in 1958) ± 300 years was found in the right rear of the cave during last days of the last season - the 4th or 1960 season. It is then, that the skeletal remains of 35 individuals were recovered. In addition to the early human remains found, what made the discovery important was the recovery of burial goods associated with the burials - goods that were not found in the excavation of a Proto-Neolithic cemetery in Shanidar Village (see below).

Solecki noted the richness of the goods buried with infants and young children suggested that the parents lavished much affection of their young. The people of that time would also have had to believe in an after-life for otherwise there would be no reason to bury articles with the dead.

Choosing to create a cemetery at the rear of the cave has its own implications.

Zawi Chemi Shanidar Village's Prehistory

In the village of Zawi Chemi Shanidar village, which lies 4 km downstream from the cave, an excavation has revealed a basal (base) layer dated to 10,870 BP (in 1958) ± 300 years. The layer is coeval with Layer B1 of Shanidar Cave and which was dated to c. 10,600 BP (in 1958) ± 300 years. These layers fall within the brief cold period known as the Younger Dryas - a period which is thought to have accelerated the need for a dependable food source such as farmed vegetables and grains. It is the earliest known post-Pleistocene village site known in Iraq. The site measures 275 x 215 m. and is at an altitude of 425 m. The ruins of stone walls made from river boulders indicate rudimentary circular huts.

The evidence indicates that Zawi Chemi Shanidar's Proto-Neolithic population domesticated animals and made grooved tools from soft chlorite or chlorite related stone. Similar tools were also found in Shanidar Cave as well as sites in the Iranian Plateau such as at Tepe Asiab and Ganj Dareh Tepe near Kermanshah in central western Iran. Solecki remarks that in this region, grooved stone tools appeared "suddenly" during the 9,000-6,000 BCE period and spread "rapidly". Solecki believes believes "that the Zawi Chemi plain transverse and longitudinal grooved ones (stone tools) were used for making cane shafts, involving a heating process. Obviously these stones were selected by the Zawi Chemi people because of some special quality they possessed. That special quality is the fact that they are heat resistant and, therefore, specially suited to the heating they would undergo during the shaft-straightening process." Solecki surmizes that the non-abrasive stone tools were too soft to be used as abraders but rather they were used to smoothen wood or bone shafts.

Early Trade

Some of the artifacts found in Shanidar Cave's Proto-Neolithic cemetery and in its general living areas were not available locally and had to be imported by surrounding regions. This implied trade. The articles recovered include obsidian, a jet-black volcanic glass otherwise found in the Lake Van area some 200 km to the north, bitumen from the Kirkuk area some 150 km. to the south, copper (native rather than ore) from Diyarbakir some 375 km to the north-west (in present-day Turkey) and exotic stones for beads.

Flower Burial of Shanidar IV

While the skeletal remains of of Shanidar I, II, III and V indicate the individuals were killed by rockfalls, the remains of another four (three adults and one child) indicate they were buried. In 1960, during the last season of excavations, Solecki and his coworkers discovered an adult Neanderthal skeleton that appears to have been deliberately buried close to the east wall of the cave. The remains were designated as Shanidar IV. Shanidar IV was a male Neanderthal whose is estimated as having been 30 to 45 years of age at the time of his death. He was buried lying on his left side in a partial fetal position. [The skeletal remains of three other individuals - two females and one infant - were found underneath Shanidar IV and they were designated as Shanidar VI, VII and VIII respectively.

Shanidar IV's +50,000 years BP remains are particularly remarkable since they were discovered with pollen clusters from 28 plants in the soil beside the remains. During a pollen analysis of soil samples taken from around the body, two of the soil samples had whole clumps of pollen in addition to the usual pollen found throughout the site. Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, analysed the pollen clumps and concluded that complete flowers had been introduced into the cave at the same time as Shanidar IV's burial because pollen from seven of the twenty eight plants identified were found in clusters. The discovery of the pollen clumps and the range of flowers from which the pollen was derived is unique to this burial.

Ralph Solecki in his Shanidar, the First Flower People (1971) at pages 176-7, goes on to say, "In some cases the pollen appeared to be resting inside the anther, or pollen-bearing part of the flower. Mme Leroi-Gourhan deduced that no accident of nature could have deposited such remains deep in the cave. Neither birds nor animals could have carried flowers in such a manner in the first place, and in the second, they could not have deposited them with a burial. Finally, one species of flower, the holly hock, a very large, pretty flower, grows in separate, individual stands. Therefore she concluded that someone in the last Ice Age had ranged the mountainside in the mournful task of collecting flowers. The soils from the area immediately bordering the grave did not yield any evidence of flowers. This provided an additional check on the finds.

"The two samples rich in flowers, Nos. 313 IV and 34 IV, were taken from about the same level on which the skeleton lay. This was probably part of a funeral bier or preparation of some kind. A third sample, No. 304 IV, less rich in flower pollens, was collected at the heel bones. This marked a triangle of flower-pollen-bearing soil samples around the skeleton. The humid soil may have had something to do with the good preservation of the pollen. At least seven species of flowers are represented by the pollens. One species of flowers is represented by random or isolated pollens in an unusually high number. These flower families are still to be found in the geographic area of Shanidar today.

"Mme Leroi-Gourhan has identified the most numerous of the flower clusters as:

- Compositae family: Achillea type, Centaurea type (C. solstitialis), Senedo type;

- Liliaceae family: Muscari type;

- Gnetaceae family: Ephedra altissima.

The pollen clusters from two other species, in spite of their quantity, could not be identified.

"The Compositae are collectively known as the daisy family.

"At least six species of the genus Achillea are identified in the Shanidar geographic area. Its (Achillea's) common name is yarrow, or milfoil, a flower widely used in herbal medicine in the past and for application to wounds. [Our note: The commonly used name 'yarrow' is normally applied to Achillea millefolium and also for other species within the genus.] 'Yarrow' is a word derived from the Anglo-Saxon, meaning 'healer'.

"The Centaurea solstitialis L. is a flower commonly known at St Barnaby's-thistle. It is a white cotton leaved plant with rounded heads of pale yellow flowers and long yellow spikes that spread defensively outwards from the head. It is not a very inviting flower, but it has its uses today in herbal remedies and is eaten as a vegetable. The genus Senecio is represented by at least four species in northern Iraq. Of these annual groundsels, Senecio vernalis W. and K. have relatively large and brilliant yellow flowers. The name 'groundsel' comes from the Anglo-Saxon meaning 'pus swallower', undoubtedly because it is used in poultices. During its long flowering season, which lasts until late spring, this flower produces a great quantity of fruit.

"Of the family Liliaceae, the Muscari, or grape hyacinth, is a very lovely flower with a dark blackish-blue colour. At least four different species of this genus have been identified in northern Iraq. They are purely ornamental flowers.

"The genus Ephedra is included in the group called 'jointpine', or 'woody horse tail'. The flowers of this type are small and not so conspicuous as the others, but they have ramose branches that lend themselves to - the fabrication of a network or bedding. At least one of the species found elsewhere in Iraq is used for medicinal purposes.

"The Malvaceae family is represented in the pollen samples by the genus Althaea, identified by Mme Leroi-Gourhan as hollyhocks. This is a distinctive plant with a tall, wand-like stem and large flowers. Unlike the other pollens, the Althaea type Pollens do not occur in the grave as clusters, but as random isolated pollens. However, they occur in an unusually, great number here, more than the normal amount in other cave deposit samples. From the hollyhock roots, leaves, flowers aria seeds, or practically the whole flower, a variety of medicines with a great many uses can be made. These range from relief from toothache and inflammation to uses as poultices and for spasms. It seems to be the poor man's aspirin."

"From the botanical evidence, Mme Leroi-Gourhan believes that the placement of the Neanderthal IV on a bed of woody branches and flowers took place sometime between the end of May and the beginning of July. Missing are the exceedingly brilliant red anemones and other lovely bright flowers that abound on the Shanidar hillslopes earlier in the spring." Further, "With the finding of flowers in association with Neanderthals, we are brought suddenly to the realization that the universality of mankind and the love of beauty go beyond the boundary of our own species. No longer can we deny the early men the full range of human feelings and experience."

Neanderthals, Herbal Health & Haoma

While some of the plants associated with the pollen found beside Shanidar IV (perhaps we may be forgiven for calling him 'Herb') may have pretty flowers, others such as the ephedra are not known so much for their flower value as they are for their herbal value. Ralph Solecki in Shanidar, the First Flower People (1971) at page 177 states, "We do not know if the Shanidar Neanderthals were aware of the medicinal properties as well as the ornamental properties of flowers, but it is likely that as working naturalists they must have given all living plants a taste during some time in their long existence. Until we know a little more about flowers in antiquity, it would be asking too much to believe that the Neanderthals were cognizant of the medicinal properties of flowers."

What we do know is that almost all the plants whose pollen was found besides 'Herb's' skeleton have recognized health giving and medicinal purposes. These include Ephedra distachya (otherwise known as Joint Pine or Woody Horsetail), Yarrow, Cornflower, Bachelor's Button, St. Barnaby's Thistle, Ragwort or Groundsel, Grape Hyacinth, and Hollyhock - plants known for their diuretic, stimulant, astringent and anti-inflammatory properties.

The healing or medicinal use of ephedra either on its own or in combination with other plants is particularly significant for Zoroastrians whose ancient healing system is based on Haoma or Hom (please see our page on Haoma). Hom is the Iranian name for the ephedra plant.

» Top

Further reading:

|