Woman and her silk thread spinning wheel, Khotan. Image credit: silkroadsuzie

Contents

Far Eastern Lands

Page 1

Page 2

Page 2: Post Achaemenian East-West Division of Iran-Shahr

Kushan, Chionites, Heptalon / Hephthalite, Zoroastrianism in China

Related reading:

» Eastern-Most Saka

» Sogdian Trade. Zoroastrianism in China

» Iranian-Aryan Connections with Western Tibet

» Kangdez - Far Away Land Beyond the Seas

» Great Ocean Vourukasha / Frakhvkard / Varkash

Post Achaemenian East-West Division of Iran-Shahr

The traditional lands of the Iranian-Aryans, Iran-Shahr, came to be divided into an East and West group of nations after the demise of Greek-Macedonian rule established by Alexander of Macedonia. The western group of kingdoms came under the leadership of first the Parthians and then the Sassanians. The leadership of the eastern group was based primarily in Balkh (Bactria), the legendary seat of the Iranian-Aryan king-of-kings. This eastern group was from time-to-time brought under the banners of the Parthians and the Sassanians. At other times, they formed an independent block known in the literature as the Hephthalites, Chionites and the Kushans.

Kushan

Midway through the Parthian era, around the 1st century CE, we hear of a group called the Kushans who asserted their autonomy from Iran-Shahr's Parthian overlords and brought under their control several of Iran-Shahr's eastern kingdoms of Iran-Shahr. One of their leaders, a Kujula Kadphises (30-80 CE) took advantage of dissention between the established Parthava/Pahlava (Parthians) and the Saka, to break away from Parthian over-lordship and establish an independent kingdom. In doing so, in 78 CE, he established what we know of as the Kushan dynasty. His breakaway kingdom gradually took control and thereby themselves became overlords of the eastern and south-eastern Iranian lands.

Based in Balkh (Bactria, now in Afghanistan), they Kushans asserted control over territory that extended into Hapta-Hindu - India of the Indus River basin - and at one point extended to their control to include all of the Indus River basin and the Gangetic plain as far east as Benares, as well as eastern lands in the Tarim Basin on the doorstep of China. Coins minted by Kushan King Kanishka have been found in Khotan. The Kushan nation was known in Middle Persian as Kushan-shahr, and became a major power in Central Asia and northern India rivalling that of Parthia. [Also see our section on Surkh Kotal / Atashkadeh-ye Sorkh Kowtal, the Zoroastrian Fire Temple in Sorkh Kowtal, part of our pages on Balkh.] Kushan autonomy and rule of the eastern Iranian lands came to an end around 225 CE with the rise of the Sassanians.

In Western classical literature, Kushan is mentioned once by Bardaisan of Edessa in his Book of the Laws of Countries, when he discusses the 'Laws of the Bactrians who are called Kushans', and remarks on their supposedly luxurious lifestyle and promiscuous morals of their women. It is thought that It is probable, too, that the reference to the "Asiani kings of the Tochari (Reges Thocarorum Asiani)" in Pompeius Trogus' Prologue 41 and 42 refers to the Kushans. The Tochari were inhabitants of the Tarim Basin (today in China's Xinjang/Xinjiang province) and the easternmost speakers of Indo-European languages in antiquity.

The coins have inscriptions in the Greek alphabet, but the language for the main part is Bactrian. (Parthian and Kushan rule followed the expulsion of Greek-Macedonian rule and the Greek alphabet was widely understood.) The Greek language was used when depicting two Greek deities while Bactrian was used when depicting Zoroastrian entities. Other than brief early issues in 127 CE, Kanishka's coins switch to bearing Bactrian legends from 128 CE onwards. For example, the word "King," rather than being recorded as the Greek BAΣIΛEΩΣ (Basileus), was rendered in the Bactrian Shao. We can assume that in the beginning of Kushan reign, the society was multicultural and multifaith and we see an acknowledgement of other faiths in the coinage. The figures do not, as some writers suggest, represent a Kushan pantheon of gods. Beside acknowledging Zoroastrianism, acknowledging other faiths - in this case Greek, Buddhist, and Hindu - was a common practice amongst Zoroastrian kings as exemplified by Cyrus. While earlier coinage had fourteen or fifteen different images on the reverse, later coinage had only two: those with the legend Athsho (Ashi, Asha or Athra) and Miiro (Mithra).

Below are images of c. 128-150 CE Kushan gold dinars (7.8 to 8 grams each). The figure on the obverse of the coins, the left images below, has surrounding it the legend in Bactrian with Greek lettering: þAONANOþAO KA ... NηþKI KOþANO meaning 'King of Kings Kanishka Kushan'. King-of-kings is the usual Iranian imperial title. Besides the king's lower hand is what appears to be a fire altar. The reverse (right hand image) depicts a symbol sometimes called a

tamgha (a sign that some speculate might have originated as a cattle brand) and various entities. The majority of the names on the reverse of the coins are Iranian and include:

• Αρδοχþο (ardoxsho from Ashi Vanghuhi?)

• Aþαειχþo (ashaeixsho from Asha Vahishta)

• Αθþο (athsho, Atar)

• Φαρρο (pharro, i.e. farr from khwarenah)

• Λροοασπο (lrooaspa from Lohrasp)

• Μαναοβαγο, (manaobago from Manu-Vohu)

• Μαο (mao from Mah)

• Μιθρο, Μιιρο, Μιορο, Μιυρο (mithro and variants from Mithra)

• Μοζδοοανο (mozdooano from Mazdavana)

• Νανα, Ναναια, Ναναϸαο (Nana, Nanaia from Anahita?)

• Οαδο (oado Vata)

• Oαxþo (oaxsho later Oxus in Greek?)

• Ooρoμoζδο (ooromozdo from Ahromazda, i.e. Ahura Mazda)

• Οραλαγνο (orlagno from Verethragna)

• Τιερο (tiero from Tir)

|

| Kushan gold dinar (c. 128-150 CE) with name Ardochsho (Asha Vahishta) beside the figure to the right. In later years, this name would be only one of two that continued to be portrayed on the obverse. Image credit: The Coin Galleries |

|

| Kushan gold dinar (c. 128-150 CE) with name Lrooaspo beside the figure to the right Lohrasp, father of legendary King Vishtasp of Bactria is revered as a saint. Image credit: The Coin Galleries |

On the reverse (the image to the right) of the coin shown above, is a figure of a man riding a horse holding a diadem with the legend reading Lrooaspo in Greek. Several authors, for reasons best known to them but unknown to this author, conclude that the Δ (delta, D) in the has been replaced by a Λ (lambda, L) and therefore the name should read Drooaspo. There is no reason for this. Lohrasp, the father of legendary Bactrian king Vishtasp is revered as a saint by Zoroastrians and is depicted on current iconography. And further, while asp means horse in persian, the name Lohrasp has little to do with owning horses - in the same way that the name Smith now has become a name and few Smiths are blacksmiths.

|

| Kushan gold dinar (c. 128-150 CE) with name Miiro (Mithra) beside the figure to the right Mithra with a sun-like halo, appears to be holding the moon in a firm grasp The king is wearing a hood sometimes called a bashlyk / bashlik, a conical headdress, but with trailing tassles. Image credit: The Coin Galleries |

|

| Kushan gold dinar (c. 128-150 CE) with name Athsho (Asha/Ashi/Arta) beside the figure to the right Athsho and Mithra were the only two entities found represented on later coins Image credit: The Coin Galleries |

Kushan Royal Diadem - Farshiang or Cydaris

|

| Investiture of Ardeshir I (224/6-241 CE), founder of the Sassanian dynasty Ardeshir receives the ring of kingship (farshiang/cydaris) from an individual carrying a barsom - likely a priest (magus) or senior family member. |

In the images above, we see the king as well as several entities on the reverse wearing a headband with tassels. We notice the tassels even when the king is wearing a crown. Two of the entities on the reverse also hold the tasselled headband in an extended hand. Some see this as a wreath, but it could be a headband that was rigid similar to a present day Arab shemagh. It has been called a farshiang or cydaris. A diadem is usually thought of as a bejewelled headband. We use that term advisedly here. We are told that in the Achaemenian, Parthian and Sassanian tradition, the diadem could have been made from silk. After he had defeated Persian Achaemenian king Darius III in 330 BCE, Alexander of Macedonia started to wear a diadem - perhaps to indicate that he had assumed the role of emperor of the Persian Empire. [The image of the Achaemenian Farohar motif displayed on our home page banner has a ring being held in the hand of the figure - but we cannot be sure this is a farshiang or cydaris ring.] The depiction of a king receiving a farshiang or cydaris is commonly associated with Sassanian investiture scenes as shown in the image below.

The royal diadem - the farshiang or cydaris ring - is a typical ancient Iranian symbol of royalty.

Chionites

Wolfgang Felix at Iranica writes that the Chionites were, "a tribe of probable Iranian origin that was prominent in Bactria (Bakhdhi/Balkh) and Transoxania (land around the Oxus, Amu Darya, River - today's

Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) in late antiquity." Felix places the origins of the name Chion-ites from the Middle Persian, Pahlavi, Khvyon/Hvyon [citing Werner, pp. 525-29; Bailey, 1930-32a, p. 945], and the Avestan Khvyaona/Hvyaona.

[Chionites are variously known as (or the name spelt as) Xionites, Chionitae, Xiiaona, Hyon... . X usually transcribes as Kh.]

Felix goes on to state, that the first (Western) mention of the Chionites is by the 4th-century CE Roman-Greek historian Ammianus Marcellinus (16.9.4) in connection with the Sasanian Emperor Shapur II (309-79 CE). Shapur spent the winter of 356-57 CE subduing the territory of the Chionitae and Cuseni (amended from Euseni in the manuscripts cf. Markwart, Eranshahr, p. 36 n. 5), otherwise known as the Kushans. If this identification is valid, then the Chionites were likely neighbours of the Kushans.

Markwart in his Eranshahr (at pp. 77-78) equates the Khvyon with another group called the Qadish and states that they were inhabitants of Herat (in western Afghanistan today). 13th-century chronicler Bar Hebraeus wrote (at 3.159) that the Qadish - who guarded the Sassanian-Persian frontier in upper Mesopotamia from Roman / Byzantium attacks - dwelt around Mosul now in northern Iraq, Kurdistan.

By 358 CE, the Chionites and the Gelani (a tribe from which the name Gilan - now a SW Caspian coast region - is derived) were serving in Shapur's army (Ammianus, 17.5.1), suggesting that the Chionites and Cuseni/Kushans were vassals of the Sassanians. The Chionites and Cuseni/Kushans made up the main contingents (the others being the Albani, Gelani, and Sacae/Saka) in Shapur's 359 CE siege of Amida (modern Diyarbakir in south-eastern Turkey) (cf. Ammianus 19.2.3; cf. Göbl, II, p. 287). Amida was then held by Roman Emperor Constantius II (317-61 CE) and Shapur's army laid siege to the city's eastern walls. In one particular battle, Grumbates the king of the Chionites, lost a son in the battle. Ammianus (at 19.1.7-19.2.1) vividly describes the subsequent funeral ceremonies and cremation.

[We pause our discussion on the Chionites to mention that the thirteenth nation in the Avestan scripture's Book of Vendidad's list of nations, is Chakhrem, otherwise called Kakhra. The location of this nation has not been identified, but the Vendidad states that while the nation was brave and righteous (surem ashavanem), the people practiced cremation. We find Chakhrem mentioned in the Avesta's Dravasp (also Drooasp and Gosh) Yasht 9.2: Yukhta-aspam vareto-ratham (kh)hvanat-chakhram where it is taken to mean the wheels of a chariot.]

Felix mentions that in the Avesta's Yashts 9.30-31 and 19.87, the the Khvyaon/Hvyaon were characterized as enemies of King Vishtasp, the patron king of Zoroaster." Further, In the Pahlavi tradition the Khvyon were among the enemies of Sassanian king Peroz (459-84 CE) in his struggle against the Hephthalites in the later 5th century CE (cf. Bailey, 1954, p. 20; Klíma, pp. 119-20, 122-23). In the prophetic Zoroastrian text, the Bahman Yasht, (4.58) the Khvyaon are

apparently mentioned along with the Turks, Khazars (see Bailey, 1943-46, pp. 1-2), and Tibetans, among the peoples destined to conquer Iran (cf. Bundahishn [TD 2], pp. 216-17; tr. Anklesaria, pp. 278-79; Bailey, 1954, pp. 13-14) (Greater

Bundahishn 33.18?). B. T. Anklesaria's translation of the Bahman Yasht 4.58 has, "And dominion and sovereignty will come to the non-Iranian slaves, such as the army of the Turk, the A-tur and the Topit, such as the Audrak, the Mountaineer, the Chinese, the Kawulik, the Sughdian and the Aruman; and the white army apparelled in red (?) will have sovereignty over my Iranian villages; their mandate and will will spread over the world."

(Greater Bundahishn 33.18 states, "Again, Khushnavaz, the ruler of the Ephtalites came, and killed Peroz. Kavat and his sister handed a fire altar to the Ephtalites as security." Here we have mention of a group called the Ephtalites/Hephthalites in translation.

Heptalon / Hephthalite

About 420 CE an Iranian speaking group called the Hephthalons (Hephthalites; so-called White Huns) established itself in the eastern Iranian lands and achieved some measure of autonomy from the Sassanian overlords. They put together a confederation of Bactrian, Sogdian, other Eastern Iranian-Aryan peoples, as well as the Saka, and ruled the Eastern Iranian lands briefly until about 557 CE when they were defeated by Sassanian king Khosrau I. The extent of Hephthalite rule extended at some point to include all of the eastern Iranian lands, including Hapta Hindu (Indus River basin, India) and what is today the Xinjiang Uygur province in China. The Hephthalites spoke an Iranian language and used Iranian-Aryans names such as Mihirakula (Mithra-Begotten). Since Turkic peoples had already begun to migrate to Iranian lands, the peoples under Hephthalite rule in all probability included Turkic peoples and peoples who were a product of Iranian-Saka-Turkic intermarriage (today we see an interesting blends of features amongst the peoples of this region).

Zoroastrianism in China

[Please also see our main page: Sogdian Trade. Zoroastrianism in China]

The oldest existing fragment of an Avestan manuscript was discovered in Dunhuang a city in the Gansu province of China. The manuscript dates to the 10th century CE. Evidence of a Sogdian settlement has also been found in the ancient the Chinese capital of Luoyang. The British Library also has a letter written by Princess Jun Zhezhe of the Guangzhou Uyghurs (also spelt Ganzhou Uighurs). In the letter, the princess "mentions lighting a fire in the Zoroastrian Fire Temple in order 'to bring prosperity along the road'."

At Turfan, in Xinjiang province, Chinese documents found in the cemeteries of the city mention several hundreds of Sogdians, and a fragment of the customs register regarding the caravans shows that among 35 operations, the Sogdians were involved in 29.

The Uyghurs are a Turkic people who now populate the far western Chinese province of Xinjiang, the province we have discussed above and which contains the cities of Kashgar/Kashi, Yarkand, Khotan/Hotan and Turfan. Gansu lies on the Silk Road just east of Xinjiang province and the great Takla Makan Desert.

|

| Aryan Silk Roads showing the Chinese and other cities along the route |

East Turkistan

The traditional lands of the Iranian-Aryans, Iran-Shahr, listed as sixteen nations in the Zoroastrian scriptures', the Avesta's, Book of Vendidad; as described in Ferdowsi's epic poem the Shahnameh and as listed in the Achaemenian era's list of nations of the Persian Empire (excluding African and European nations) came to be divided into an East and West group of nations after the demise of Greek-Macedonian rule established by Alexander of Macedonia.

|

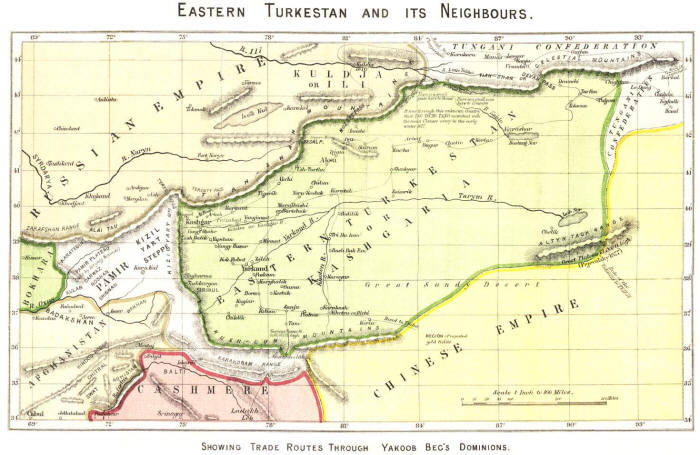

| Eastern Turkestan (Kashgaria, now Uygur in China) 1872 CE. Click to see a larger map |

The eastern-most lands that from time-to-time became part of the Iranian-Aryan sphere of influence were later known as Eastern Turkistan. The pattern of historical change appears to be as follows. The Iranian Saka lands and the lands to the east of then (Afghanistan and Tajikistan being exceptions) were occupied by a Turkic peoples. When the leadership of these Turkic peoples converted to Islam, their entire population converted as well. The rough extent of previous historic Iranian, Iranian-controlled (control fluctuated) or Iranian-influenced lands can be seen as those whose populations now embrace Islam. In present-day China, this includes parts of Xinjiang Uygur province. There are some Avestan lands (nations named in the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta) that are as yet unidentified. For the main part we place them to the west of Tajikistan. It is within the realm of possibilities, that lands east of Tajikistan could have been a part of the Avestan nations.