Contents

Zoroastrian Wedding Customs

Introductory Page

Indian Zoroastrian (Parsi & Irani)

Page1

Engagement

Page2

Pre-Wedding Festivities

Page3

Wedding Day

Page4

Marriage & Reception

Iranian Zoroastrian

Page 1

Yazdi Wedding Customs

Page 2

Modern Iranian Wedding Customs

Page 3. The Wedding Day

» Page 1: Overview & Organization

» Page 2: Pre-Wedding Festivities

» Page 4: Marriage Ceremony & Reception

Ceremonies Before the Marriage

The intention of the pre-wedding rituals on day of the wedding are similar to the pre-navjote ceremonies on the day of the navjote or initiation. These rituals help the couple enter and conclude the marriage in a state of physical and spiritual purity.

There are two ceremonies that serve this purpose: the ritual bath or nahan (or nahn) that takes place at the bride and groom's home before they start to dress themselves for the wedding ceremony, and the achu michu that takes place before the bride and groom enter the sacred space where the marriage ceremony will be performed.

Nahan or Nahn / Ritual Bath

For a description of the nahan please see the page on purification.

While at their individual homes, or at a fire temple, the bride and groom take a ritual bath supervised by a priest. The bride and groom pray with their respective family priests who also guide them on the procedure of the ritual. After praying, the bride and groom bathe themselves while their priests wait outside the bathroom door or in the living room.

After the the bride and groom have finished bathing and dressing themselves in their wedding clothes, they emerge for the concluding acts of the nahan ritual.

|

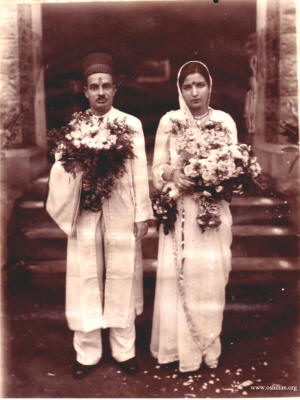

| Groom wears a dugli & fetah Bride a white sari Photo: Neville Fitch, Bethesda MD |

Garments & Accessories

The priests, the couple and the witness who stand behind the couple, all wear white garments and cover their heads. Zoroastrian cover their heads when they pray or attend religious ceremonies.

Before leaving their homes for the wedding venue, in a short ceremony, the groom and bride are given a coconut and bouquet to hold.

A tila with embedded rice is placed on their foreheads - a long vertical tila for the man and a round tila for the woman.

In the photographs to the left and below, note the garlands, bouquets and coconuts in the hands of the couple.

Groom's Garments

|

The groom wears a thin and flowing thin white robe, a dugli, with white trousers and a ceremonial hat or a simple prayer cap. There are two principal types of ceremonial hats: a flat topped hat called a fetah and one with a tapered top called a pagri or pughdi. Tassels tied together close the opening in the front of the dugli. Wrapped around the man's arm is a shawl (see photograph above).

|

| Bride Photo: Mark Fitch, Bethesda, MD, USA |

In previous times, the groom would have worn a jama-pichori or sayah, a loose flowing garment with folds and curls seen in the photograph in the banner at the top of the page.

Bride's Garments

The bride wears a white sari and blouse. The sari is often intricately decorated. A part of the sari is used to cover the bride's head. The head of both women and men are always covered during the religious parts of the ceremony, and can be uncovered once the ceremonies are over.

Venue

Zoroastrians do not usually perform weddings in a place of worship (as this would exclude non-Zoroastrians in many Indian fire temples), though halls adjacent to a temple are used at times.

Venues with large grounds are a popular choice, weather permitting, for outdoor weddings, while hotel halls are sometimes used for indoor weddings.

The type of venue is not important as long as it is clean and can hold the number of people participating in the wedding.

The Gathering

|

| The gathering. The group to the left have gathered around the couple during the ara antar (see below), after which the couple will move to the wedding platform to the left Photo: Mark Fitch, Bethesda, MD, USA |

Zoroastrian weddings are for the main part events where both families invite numerous relatives and friends, the number being decided by negotiation. [The families risk hurting feelings if they neglect to invite people who feel entitled to an invitation.]

Members of the gathering have a role: they are called an anjuman, a formal gathering with an official role, and are there to bear witness and add their blessings to the marriage. Usually, a reception follows the marriage ceremony. If guests are invited to both the marriage ceremony and reception, it is not considered good form for the guests to miss the wedding ceremony and arrive just in time for the reception. However, even when guest do attend the marriage ceremony, it is, regrettably, not uncommon for the guests and their children to pay no attention to the wedding ceremony but to chat or play amongst themselves. Doing so diminishes the solemnity of the ceremony and for this reason some wedding ceremonies are limited to close adult family members, a development that unfortunately removes the traditional public witness aspect of a marriage ceremony.

Guests that are invited to witness the marriage ceremony are expected to gather and seat themselves before the arrival of the groom and bride, and not to wander in after the ceremonies have started.

The two family priests who have been in attendance since the nahan, also arrive at the venue before the groom and bride.

» Site Contents

Wedding Area, Platform or Stage

|

| Wedding platform and chairs Photo: Mark Fitch, Bethesda, MD, USA |

A modern Zoroastrian marriage ceremony is generally conducted on a raised platform or on a low stage decorated with predominantly white flowers with some red flowers added. White and red are colours customarily used in Zoroastrian festivities, white representing purity and honesty, and red representing fire and vitality. The use of raised platforms or a low stage is not traditional but helps the audience better view the ceremonies.

In the past, the ceremony would have been conducted sitting on a sheet called the sofreh spread on the floor - as is the current practice for the navjote (initiation) and jashan (thanksgiving) ceremonies.

The sofreh, a sheet of simple white linen or cotton, defines the sacred space in which all Zoroastrian ceremonies take place. Participants in ceremonies such as the navjote, remove their shoes before entering the sacred space, and either sit directly on the sheet, or on a low stool, called a patlo, placed on the sheet. Ritual items are also placed on the sheet. Sitting on the floor is a mark of humility and grounding, literally and figuratively. These days, the couple sit on chairs placed on the sofreh and they do not remove their shoes.

During the first phase of the ceremony, the chairs are placed facing one another (see ara-antar below).

During the second, or religious phase of the ceremony (see page 4), the chairs are moved so that the couples sit side-by-side, with the groom's chair placed on right of the bride's chair. The layout of the room needs to be such that when the chairs are also repositioned, they both face the gathering. In addition, if the marriage ceremony is conducted during the day, the couple need to sit facing the sun during the second phase. If the ceremony is conducted at night, the couple face the direction of the rising sun or east.

Alternatively, the two phases of the ceremony can be conducted on two separate sets of chairs, the first set being closer to the gathering enabling all family members to gather around the couple, and the second set being placed on the stage.

Two trays containing rice and rose petals that the priests will use, are placed besides the chairs at the front of the stage. Once the priests start the religious part of the ceremony, the trays are repositioned closer to the priests, if needed, to enable the priests to collect handfuls of rice and petals which they will shower on the couple throughout the prayer ceremony.

|

| Trays containing rose petal and other items |

Other items are placed near the chairs on a metallic tray. These include two lit candles which the couples will use to jointly light a third candle or oil lamp (devo), a censer or brazier of burning incense or espand seeds, as well as a small metallic container containing ghee (or clarified butter - representing gentility, courtesy, understanding and loyalty) and molasses (representing sweetness and good temper). In Yazd, oil instead of ghee and molasses is used - oil that the couple will sprinkle on the threshold of their home. The groom and bride's sace or ses will contain other traditional items such as cones of sugar, rose water, a container of kunkun (vermillion paste), a devo or oil lamp and a garland or flowers. [In Iranian weddings (other than Yazdi weddings), the items are spread all over the sofreh or sheet, while in Yazdi and Parsi weddings, the items are collected and placed on trays called a sace or ses by Parsis.

The groom's sace or ses that has been used since the Rupia Peravanu is placed to his right while the bride's sace is placed to the left of her chair on the stage.

|

| Groom's sace or ses containing sugar cones & other items Photo: Neville Fitch Bethesda, MD, USA |

|

| Arrival of the groom escorted by his father Behind them, two female relatives follow carrying the groom's sace on their shoulders Photo: Neville Fitch, Bethesda, MD, USA |

Arrival of the Couple

The wedding ceremonies start with the arrival of the groom and bride.

At the appointed time the groom and bride are escorted by assistants and family members from their family homes to the wedding venue. The groom arrives first and is seated before the arrival of the bride.

When they arrive at the venue, the groom and bride are escorted to receive the achu michu ritual by their respective fathers or guardians. The bride walks holding her father's arm. Two married female close relatives follow closely behind walk behind carrying the groom or bride's sace or ses between them at shoulder height.

The photographs to the left show the arrival of the groom escorted by his father. The two female relatives following closely behind can be seen carrying the groom's sace covered with flowers. The sace was later placed on the marriage platform.

The bride's sace often has a sari among its various items.

Achu Michu

|

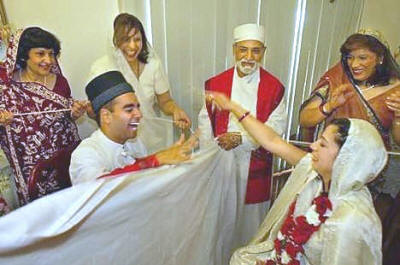

| Bride's mother performs an achu-michu on the groom |

For a description of the achu michu please see the page on purification.

The achu michu is the final step in preparing the couple to enter their matrimonial union in a state of spiritual purity, and compliments the earlier nahan or ritual bath (see above). While the nahan was intended to cleanse the person physically and spiritually, the achu michu is intended to remove any lurking evil and the evil eye.

Unlike the nahan ritual which is based on religious principles and is supervised by a priest, the achu michu has no religious underpinnings and is not performed by a priest. Instead, the achu michu is performed by the mothers of the groom and bride when the latter arrive at the wedding venue and before they enter the sacred space where the marriage ceremony will be performed. The achu michu is also performed on those family members who will station themselves on the sacred space of the marriage platform during the marriage ceremony.

|

| Aarti: groom's mother places a garland on the bride |

One system for performing the achu michu is for the bride's mother, or eldest woman relative, to perform the ritual on the groom, and for the groom's mother, or eldest woman relative, to perform the ritual on the bride.

If the groom and bride have not arrived adorned with a tila of vermillion or kunkun with embedded rice on their foreheads, a garland of white and red flowers around their necks, a coconut wrapped in string around in one hand and a bouquet in the other hand - they are given these items after the achu michu.

The tila (vermillion or kunkun) for men is a long, vertical mark, while the tila for women is round - an obvious reference to their gender. A paste of the vermillion is prepared before hand and is applied to the forehead of the recipient by the officiating woman with a short stick similar to a matchstick. Sometimes, the officiating woman will use her thumb to make the mark. While the paste is still wet, the woman performing the achu michu takes a sufficient quantity of uncooked rice in the palm of her hand and presses the rice into the recently applied vermillion paste. (For photographs of the application of a tila, please see the madhavsaro ceremony.) The paste dries on the forehead and the rice adheres to the paste. (The paste and rice are easily removed by washing and the paste does not leave a residual mark.)

Putting on the garland is called aarti.

Var Behendoo - Hand Dipping

When the bride's mother has finished performing the achu michu on the groom, the groom steps onto the marriage platform and seats himself on the left chair (as seen facing the platform or stage) to await the arrival of the bride. He will not however be allowed to remain idle.

Shortly after he has seated himself, women from the bride's family present him with a pot, or chambooru, filled with some water. The groom, dips his hands into the pot and while doing so, drops in a silver coin. This is his preview of the haath borvanu (hand dipping) ceremony the will follow the marriage and which is described on the next page.

First Phase of the Marriage Ceremony

|

• Ara Antar - Curtain of Separation

• Hathevaro - Joining of Hands as

Soul Mates

• Chero Bandhvanu - Binding the Couple

After the bride has arrived and seated herself opposite the groom, close family members gather around the couple. Two of the family members (or the priests), hold a sheet so that it hangs between the couple, preventing them from looking at one another. The size of the sheet or curtain is such that it extends down to the knees of the couple when hung upright. The curtain symbolizes the separation that has existed between them and the ritual is called the ara antar.

|

| Hathevaro: Tying the right hands together |

Next, the priests place a few grains of raw rice in the left hands of the couple. The groom's priest then places the bride's right hand in the groom's right hand at the bottom edge of the curtain, and wraps a string around their clasped right hands seven times while reciting the Ahunawar (Yatha Ahu Vairyo) prayer. This binding of the hands in handshake position is called hathevaro.

The same string that binds their right hands is also wound around the couple's chairs seven times, the number seven signifying the divine heptad of God and God's six attributes or archangels, the seven regions (keshwars) of the earth, and the various heptads of values and qualities that feature prominently in Zoroastrian theology, philosophy and ethics.

In some ceremonies, the string around the chair is replaced by a cloth wrapped around the chairs once. The string or a long piece of cloth, are joined by a final knot that symbolizes the bride and groom's desire to unite of as a lifelong couple. [For reasons of symbolism, it is preferable if the string encircles the couple only and does not encompass other participants. Four individuals can hold the string at the four corners around the chairs.]

There is added symbolism in the ritual: while the thread that binds them is weak and can be broken easily as a single strand, it gains strength when wrapped seven times - strong enough that the bonds cannot be easily broken, if at all.

The priests recite one ahunavar (yatha ahu variyo) prayer for each circle of the string and finish reciting the seventh ahunavar at the moment the seventh encirclement is finished. This is the cue for those holding the curtain of separation to lower or drop the curtain, a lowering that symbolizes the removal of the spiritual divide that had existed between the couple. The removal also permits the process to unite them as husband and wife to begin - not, however, before the interjection of a moment of levity.

The finishing of the the seventh ahunavar prayer by the priests also signals the moment when the couple can shower each other with the rice they had been holding in their left hands. Neither will waste any time, for the one who throws the rice first is considered to be one who will 'wear the pants in the family'.

|

| Ara antar: Rice throwing Also notice the string around the couple - Chero Bandhvanu |

Their eagerness to be the first to shower the other with rice is, however, supposed to demonstrate their eagerness to take the lead in showing respect and love for one another. Unspoken in the jesting is the message that there are no assumptions or pre-assigned roles of dominance in the relationship and that each person has to take the initiative and lead in strengthening the bonds between them. The one who takes the initiative, leads by example.

If the curtain has been lowered but not dropped, it is dropped after the couple finish the rice shower. The right hands of the couple are untied, sometimes only after the bride's women family members have extorted money from the groom. Behind the silliness in the untying of the string lies an important message: the bonds of the string are to be replaced by the bonds of mutual love and respect, the same love and respect that has removed the divide between them.

The couple rise and the chairs are either rearranged in the manner described above. Alternatively, if the ara antar had taken place in front of the wedding platform, the couple are invited to sit on two pre-arranged chairs on the stage. The couple now sit next to and beside one another, with the groom on the bride's right. This change in seating compliments the symbolism throughout the ara antar: barriers and gulfs that would have prevented the bride and groom from forming a family unit have been removed, and they are ready to enter the next steps of the ceremony together.

» Top

» Page 1: Overview & Organization

» Page 2: Pre-Wedding Festivities

» Page 4: Marriage Ceremony & Reception