Page 2

Contents

|

Designs & Motifs

|

Bird of Paradise or Simorgh from Shahnameh.

Image credit: Wedding Sutra |

The gara's border design include Persian themes such as:

• Birds: cranes, birds of paradise or simorgh, sparrows and swallows (for some reason a few Zoroastrians consider the peacock & perhaps the peahen to be inauspicious).

The design element of birds in pairs were popular in the Aryan lands and could have been taken to China by Sogdian (Sughdi) traders during the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE).

In this manner, there are several motifs that are common to Chinese and Aryan cultures albeit with local adaptation and style.

• Flowers: roses, lily, lotus, peonies, jasmine and chrysanthemums. Thirty flowers representing thirty angels for each day of the month.

• Plants, Cypress tree, others trees and graceful, weaving tendril stems.

• Typical Chinese designs include pagodas, pole driven boats, riverbanks, bridges weeping willows, bamboo, flowers, birds such as cranes, human figures in Chinese dress and even soldiers (cf. the willow pattern used on English china-ware plates).

• According the Brenda Gill, in Chinese design each of elements represents a characteristic. Of the 'Flowers of Four Seasons', the plum blossom is a symbol of winter, the peony and orchids are symbolic of spring and good fortune, the lotus is the symbol of summer, and chrysanthemum is symbolic of autumn and longevity.

Further, the fast-growing and green bamboo stalks represents vitality and strength. In addition, the bamboo's ability to recover and stand upright after bending in a storm is symbolic of a resilient spirit.

The pomegranate full of seeds represents fertility, and the peach brings a long and healthy life. Of the creatures, the crane symbolises immortality, the horse represents speed and intelligence, butterflies symbolize summer and joy, and the peacock stands for nobility. She adds that ribbons fluttering from the beaks of birds represent marital bliss, and given that this is a popular western images as well we wonder about the origins of the symbol.

• A very specific Chinese design features the Eight Immortals, who carry symbols of prosperity and longevity such as the fan or lotus stem. The design is often part of a panel that includes scenes from nature and particularly the sacred or divine fungus, a symbol of immortality.

• The classic Sassanian motif consisting of small circles of pearls appears to have been adopted by Chinese artisans via Zoroastrian / Sogdian (Sughdi) traders during the era of the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) and was then re-imported to India as gara motifs by Parsi traders.

• The boteh (otherwise called the paisley when copied by the English) motif appears to have similarly travelled to China and travelled back to India in a different style adapted by the Chinese. However, the Parsi traders could very well have taken samples of designs they desired to the Chinese craftspeople and asked the later to include them in their embroidery.

• According to the Parzor Project, "The Rooster is a widely used motif in Parsi embroidery. In Zoroastrian culture the rooster signifies the day and death of the evil night, it is also the symbol of Sarosha. The rooster is also commonly used in Chalk and Toran designs. Zoroastrian children were made to wear jhablas (a child's tunic) with rooster motifs to ward off evil."

|

The kanda-papeta design on a gara blouse from the early 20th cent. The border design does seem to have a peacock

that a few Parsees shun. Image credit: Embroidery by Brinda Gill |

|

Unusual Design Names

|

Chakla-chakli design made with the ari stitch at Parzor's workshop.

Image credit: Craft Revival |

There is a design styles called the kanda-papeta (meaning onions and potatoes) which consists of pink and yellow circles (polka dots). The pinks circles are onions, and the yellow circles are potatoes.

The karolia gara has a spider-like design on flowers.

The chakla-chakli gara has contra-positioned birds such as male and female sparrows or swallows as part of the design (see image right bottom).

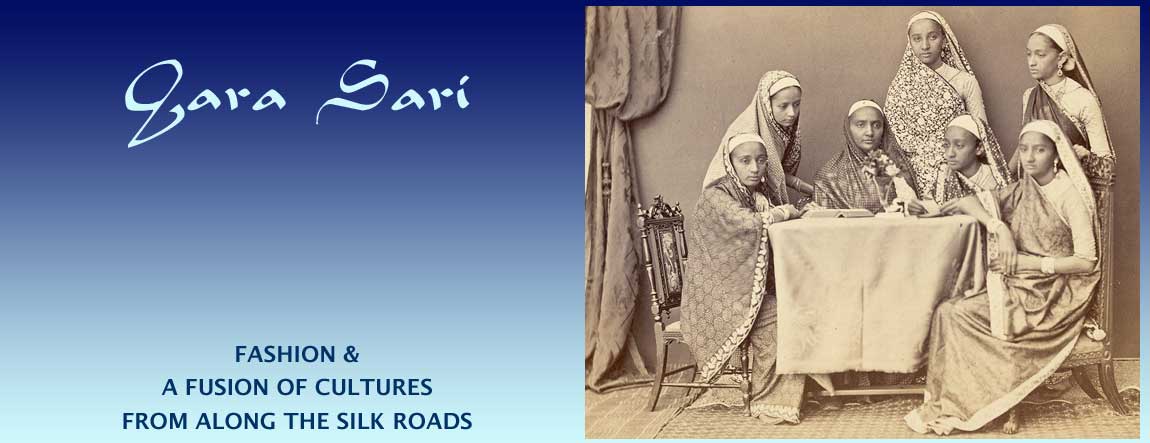

Making a Gara

The making of a traditional gara - and this does not include the manufacture of the fabric - is done entirely by hand and employs individuals with different skills.

Initial Steps

|

Page from a 19th century Chinese pattern book on rice paper.

Image credit: Don Cohn, New York |

First comes the initial concept, choice of fabric and colours, the overall design, design of the border and motifs and perhaps designs of the body elements.

The preparation and dying of the embroidery thread is a specialized art in itself. The drawing of the individual design elements on paper may employ an individual skilled in this task after which the design is transfered to the fabric (or portion) stretched on a frame. This may be done by punching holes in the paper drawing and rubbing a pigment through the holes. There are other traditional embroidery transfer techniques available as well. Connected border designs require the design to be repeatedly traced forming a motif seamlessly integrated into a continuous design.

Embroidery

Embroiderers then begins to 'paint' with a needle using as many as 20 to 30 different colour thread made from silk, cotton and even gold thread to 'paint' a single flower!

Embroiderers specialize both in the embroidery design and in the type of stitch best suited to make the pattern or achieve a certain quality or look. As such the making of the gara may employ several embroiderers working simultaneously. The more complex the gara, the greater will be the number of embroiderers needed in its making. A typical gara is made by four to six embroiderers working simultaneously around a frame that holds the gara. Depending on the complexity and density of the border's design, the making a hand embroidered gara takes between two and nine months to complete.

|

Detail of Indian Zardozi work from Awadh - 19th century.

Image credit: Woven Souls |

In an article by Pushpa Chari in fravahr.org, we read that "the original gara had silk floss* embroidery in white and occasionally in pastel shades on sal gajji silk, which was generally purple, red and black in colour." "The stitches were satin stitch** with variations of extended, bound, voided and embossed as well as French knots. The Gujarat mochi (cobbler) stitch and the Deccan zardosi stitch were also incorporated while ari is now being used."

A laborious and painstaking method of embroidery used to produce ornate and intricate designs is the ancient Persian embroidery technique called the Zardosi / Zardozi /Zardoosi stitch. Zardoozi embroidery uses, instead of silk, a metal thread called kalabattu. The name Zardosi (which sounds very close to Zardoshti, a form of Zartoshti meaning Zoroastrian) comes from the Persian words zar meaning gold and dozi meaning embroidery.

On her webpage, Brenda Gill states, "Gara motifs were generally embroidered in satin stitch**, long and short stitch, and the tiny kha-kha*** or seed-pearl stitch akin to a minute French knot. The kha-kha stitch forms a delicate textured area - as if the cloth is covered with beads, and was worked for complete motifs or the centres of flowers. Being a small stitch, the kha-kha proved to be a strain on the eyes, and satin stitch was more frequently worked. There are samples of textiles worked with satin stitch in neat two-sided embroidery."

Notes on the description of stitches mentioned above:

*Embroidery floss is a common type of embroidery thread made up of of six loosely-twisted strands, the last of which has the most sheen.

**A satin stitch otherwise called a damask stitch is a series of flat stitches that completely cover a section of the background fabric. The stitches can be of different colours or hues in order to give the appearance of subtle shading.

***Tales of different and secretive embroidery techniques include the mysterious kha-kha (or khakha), or forbidden stitch - which according to legend, can cause an embroiderer to go blind.

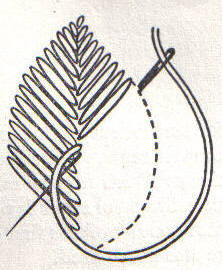

A type of Indian embroidery stitch is the Ari / Aari / Zari stitch made by using a long 'aar' needle (which is an adaptation of the cobbler's awl) and vertically piercing the fabric stretched on a frame (see image to the right). The embroidery process involves pushing a long needle through the fabric and then attaching a thread to the needle tip on the other side of the fabric. Pulling the needle back up brings with it a loop of thread. the next stitch is made by pushing the needle through the loop and pulling up another loop through the previous loop. The process is repeated. The resulting fine, flowing, curvilinear stitches that look like a chain are well suited to produce peacock, parrot, elephant, and flower designs. The aari stitch is also called a mochi stitch since it is the same type of stitch used by cobblers called mochis in India.

|

Detail of an old gara sari border employing the satin stitch.

Image credit: memssaab story |

|

Enlarged border detail of an old gara made in Gujarat, India. Note the French knott

which is actually much smaller than shown. The entire border is 2" wide.

Image credit: memssaab story |

|

Care & Storage

According to Jenny Desai at In Search of the Zoroastrians "The old garas could not be washed and had to be handled very carefully. The fabric would shred and the colours made of vegetable dyes would run (and discolour the embroidery work as well). The garas were stored in intricately carved teak chests, with pepper corns tied in muslin cloth and sandalwood sticks, to keep away insects and moths that fed on the natural silk. Unused, the garas could deteriorate."

"... the best way to store a gara is to wrap each one separately in white muslin and place it flat. They must not be hung. Silks, and particularly garas must never be stored in plastic. Buying a new gara is like purchasing jewellery which can be handed down to the next generation as an heirloom. When well looked after and properly stored, a gara can last about 300 years."

Without access to dry-cleaning of the highest standard, we must wonder how the gara was cleaned over a hundred years ago.

Tanchoi Sarees

The UNESCO Parzor Project, Shernaz Cama director, states that tanchoi was named "after the three (tan) Parsi Joshi brothers from China (Choi). Gandhiji himself visited the Joshi family and invited him (them?) after Independence to organise the Tanchoi Centres, which today exist across India." Further on in their web page they state, "The famous Tanchois of Surat (and later of Benares) originated with three Parsi Jokhi brothers (tan -Choi) who learnt the technique in China and brought it to India. The Parzor team has been able to locate some of the first original sample-pieces of Tanchoi made on the looms with the seal of the family woven onto them." We note that the name used in the previous quote was Joshi, while in the latter quote it is Jokhi. Further, it is unusual for China to be called Choi rather than Chin or Chini for Chinese - unless Choi is used as slang for Chinese. Choi is a Chinese family name. Further, according to Parzor, "...this art was taught to the weavers of Benares and Tanchoi weaving centres set up in various parts of India through the urging of Gandhiji and Kamladevi Chattopadhya."

Another story quoted variously states that around 1856, three (i.e. 'tan' is Gujarati) Parsi Chhoi brothers from Surat, Gujarat travelled to China to study the Chinese silk weaving industry and came back a proprietary technique they used to create a sari called the tanchoi, so named after the three (tan) Chhoi brothers. The tanchoi sari has since been regarded as a sari peculiar to Surat and was originally worn primarily by Parsi women as was the gara. To this writer's knowledge, Choi or Chhoi is not a usual Parsi name. It is of course a Chinese name. The Parsi traders were known to have brought over an entire community of Chinese embroiderers to India (see Chinese Embroiderers in India above) and there is no reason why they couldn't have brought over weavers as well.

It appears that the difference between the gara and the tanchoi is that the border and any designs in the body of the sari are woven into the sari rather than embroidered. As a result, even when the fabric of the sari is silk, the tanchoi would still be less costly than a gara. Nowadays, the weavers of Varanasi have produced an even less expensive version. There are interesting parallels with the termeh fabric of Kerman and Yazd - prized fabric that are also a part of Iranian-Zoroastrian heritage.

Fabric variations include self-patterned or figured silk. Figured silk fabric contain a relief pattern that is repeated throughout the body of the fabric. Figured silk tends to have a heavier body than plain silk fabric. The weaving technique for multi-coloured designs in the body or border can be so elaborate so as to create the illusion of embroidery.

The Modern Gara

|

A modern gara with a matching blouse

Image credit: A Zoroastrian Tapestry Art Religion and Culture*

by Pheroza J Godrej & Firoza Punthakey Mistree (also see *note below) |

|

A modern gara set: gara, blouse and light tunic-coat.

Image credit: Amrich Designs |

|

[* Note: The image above left is part of an article by Dr. Kalpana Desai titled "The Tanchoi and the Gara Parsi Textiles and Embroidery" at p. 199. The photographer for the image was Gautam Rajadyaksha and the model, Meher Jesia. Also see the image titled "Traditional Zoroastrian Yazdi wedding costume" at our page on Termeh, the hand-woven silk and wool fabrics from Yazd and Kerman, in the section, Heritage in Peril].

Sources & Acknowledgements

Purveen Meher-Homji

Shirinmai Mistry

» Parzor Project Home page. Dr. Shernaz Cama, director (excellent work)

» Parzor Project Textile and Embroidery page

» Memssaab Story

» Deepika Sorabjee at CNN-GO

» In Search of the Zoroastrians by Jenny Desai

» Craft Revival

» Embroidery by Brinda Gill

» Top

Also See:

|