ContentsAvestan Manuscripts |

» Site Contents |

» Related reading: Zoroastrian Avestan Languages

Manuscripts

A manuscript is a handwritten book. Manuscripts were the way in which books were produced before the invention of printing. Remnants of earliest extant (existing) Avestan manuscript date back to the 10 century CE, while the bulk of the complete manuscripts in libraries today, were written in the 18th century CE. Avestan books were not produced for use in a liturgy. Rather, the Avestan manuscript served to transmit the sacred text. The portion of the Avesta used in a religious ceremony was and is recited by a priest from memory.

We commonly think of a manuscript as a collation of flexible material which is written on in some fashion. This flexible substrate is made from either natural or manufactured material. Examples of natural material are animal hide and parchment or vegetable material such as thin slivers cut from the trunk of a tree. Papyrus and paper are examples of manufactured materials. A manuscript constructed as a book, that is, folded sheets sewn together and bound, is called a codex.

Some manuscripts are illustrated and decorated. These are called illuminated manuscripts. The Avestan manuscripts we have seen are fairly plain. Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, on the other hand, was in the past reproduced as richly illustrated manuscripts. Today, the manuscripts are prized by collectors as works of art and can be very valuable. We describe them in some detail in our introductory page to the Shahnameh.

The traditional abbreviations are MS for manuscript and MSS for manuscripts. The word manuscript appears to have originated in the late 16th century CE, from medieval Latin manuscriptus meaning 'written by hand' i.e. manual writing, and from the Latin scribere 'to write'.

The person who reproduces books as a manuscript is called a scribe. The alphabet and cursive system of writing is called a script.

Avestan & Pahlavi Scripts

The direction of writing using the Avestan (the Old Iranian language) and Pahlavi (the later, Middle Persian language and predecessor of Modern Persian) is right to left, and the shape of the letters are cursive. For an example of the Avestan alphabet see below. The range of vowel and consonant sounds in Avestan is wide in a manner similar to Sanskrit and greater than the range in Pahlavi. Some of the earliest known surviving examples of both languages date to the 3rd century CE to 4th century CE from the Sassanid era (226-651 CE). (Also see Written Avestan Texts section in our page on Zoroastrian Avestan Languages.)

Location of the Manuscripts

Today, Avestan manuscripts are widely dispersed in collections and libraries throughout the world. A project under way called the Avestan Digital Archive (ADA) seeks to make the dispersed manuscripts available digitally over the internet. The site also contains a listing and description of the libraries and collections.

Earliest Surviving Sogdian Avestan Manuscript From China

- 10th Cent. CE

|

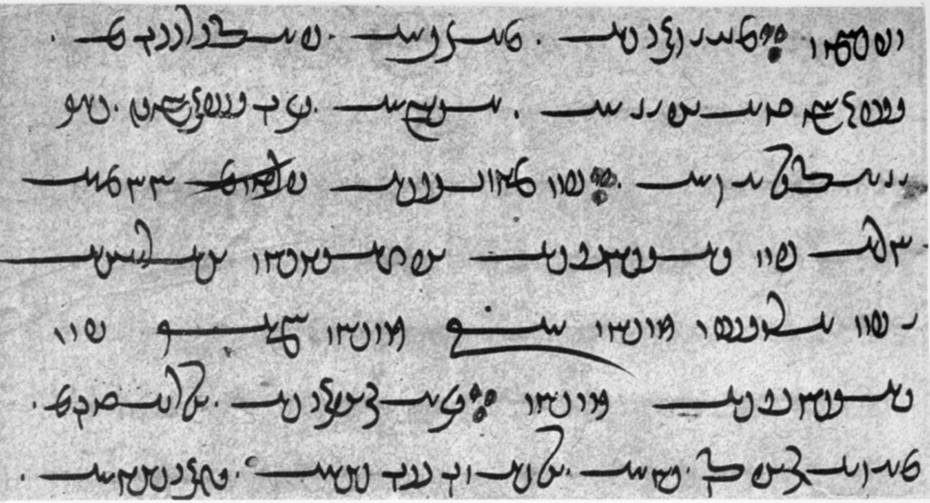

| Zoroastrian prayer, the Ashem Vohu British Library Or. 8212/84 (Ch.00289) |

The earliest surviving Avestan manuscript (the Avesta being the Zoroastrian scriptures), is a the 10th century CE fragment found in Dunhuang, China (see below). The next earliest extant Avestan texts come from Iran and India and date from the end of the 13th century ACE - three hundred years after the Sogdian manuscript was written.

The manuscript is presently housed in the British Library.

The body of the text is written in standard ninth century CE Sogdian using the Avestan script. It describes Zoroaster addressing God supreme. The preface to the text consists of two lines of the Ashem Vohu prayer written in a dialect that is similar to Achaemenid Old Persian. For example, the standard Sogdian equivalent for the Iranian Avestan asha or ashem is rtu (cf. Vedic Sanskrit) or reshtyak. The manuscript uses rtm, a form identical with Achaemenid Old Persian rtam.

|

| Library Cave, Dunhuang, in 1907 |

According to the British Library web-page, "This manuscript was one of 40,000 or so books and manuscripts hidden in one of the 'Caves of a Thousand Buddhas' - a cliff wall near the city of Dunhuang (a town on the Silk Road in northwest China) honeycombed with 492 grottoes cut from the rock from the fourth century onwards and decorated with religious carvings and paintings.

"The secret library was sealed up at the beginning of the 11th century, probably under threat from the Karakhanids who had taken Khotan in 1006.

"The cave was discovered in 1900 by the Daoist monk Wang Yuanlu who presented manuscripts and paintings to local officials, hoping in return for financial support to pay for conservation work. When the archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein arrived there in 1907, Wang Yuanlu sold him large numbers of manuscripts and paintings which are now in the British Library, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the National Museum Delhi."

Mihraban Kaikhusraw Manuscript - 1323 CE

|

| 1323 CE Mihraban Kaikhusraw Vendidad in Avestan and Pahlavi British Library MS Avestan 4, folios 265v-266r: Chapter 19, verses 6-9 |

The image above is that of a 1323 CE folio from the Vendidad written by Mihraban Kaikhusraw in Navsari, Gujarat,. In this manuscript, each sentence is given first in the original Avestan language, and then in Middle Persian Pahlavi, the language of Sassanian Iran (c. 224 - 651 AD). This manuscript is the second oldest Avestan manuscript that survives today after the 10th century CE fragment Sogdian manuscript (also in the British Library (BL Or.8212/84) found in Dunhuang, China.

According to the British Library, "Mihraban Kaikhusraw, the scribe of our manuscript, also made another copy of the Videvdat in 1324 and two copies of the Yasna in 1323, all of which survive today.

"The British Library manuscript belonged previously to Samuel Guise, Surgeon in the Bombay Army from 1775 to 1796. Guise's collection was made at Surat between 1788 and 1795, at great personal expense, while he was Head Surgeon to the General Hospital. His rarest manuscripts (according to his catalogue published in 1800) were purchased from the widow of Dastur Darab who between 1758 and 1760 had taught Avestan to Anquetil du Perron, the first translator of the Avesta into a European language.

"Unfortunately the first part of the manuscript was in such bad condition that Guise had folios 1-34 and 59-154 re-copied and presumably the original was thrown away. The manuscript also lacks the final leaf containing the colophon, but luckily this has been preserved in a later copy made from the same manuscript. Samuel Guise died in 1811 and his collection was sold at auction by Leigh and Sotheby in July 1812."

Bodleian Manuscript

|

| A page of the Yasna (28.1) at Bodleian Library, Oxford, England |

In the 1700's Thomas Hyde was an Orientalist and chief curator of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England. He was the author of a book in Latin titled Veterum Persarum et Parthorum et Medorum Religionis Historia: a history of the Persian, Parthian and Median religion. His interest in Zoroastrianism led him to issue an appeal to scholars to procure manuscripts of Zoroastrian texts.

In 1718,George Boucher, an Englishman resident in India, answered Hyde's call and managed to procure from the Parsis of Surat, a manuscript of the Vendidad Sadah (one of the books of the Avesta). In 1723, he sent the manuscript to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in the care of Richard Cobbe. The book, whose text was unintelligible to its new owners, was hung on the wall of the library by a chain, and remained a passing curiosity until Anquetil du Perron came across the tracings of four pages of the manuscript that were sent to Paris.

Du Perron Manuscripts

Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil du Perron (1731-1805) was a French scholar who studied Hebrew at the University of Paris having developed a keen interest in eastern languages and religious mysteries. He travelled to Surat, India, and there he succeeded in procuring Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts from a Zoroastrian priest Darab Kumana. Du Perron left Surat and India in 1761 with one hundred and eighty Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts and their translations.

Du Perron gave his manuscript collection to the Royal Library of Paris (renamed Bibliothèque nationale de France - the national library of France after the French Revolution).

Copenhagen / Rask Manuscripts

Danish philologist Rasmus Kristian Rask (1787-1832 CE), continued du Perron's tradition and travelled to the east in order to collect additional Zoroastrian manuscripts. He returned to Denmark in 1823, bringing with him several Avestan and of the Pahlavi manuscripts, which he deposited in the Royal Copenhagen library, the Kongelige Bibliotek. Some twenty years later, L. Westergaard added to this collection, fifteen Avestan manuscripts (numbers 35-43), purchased in India and Iran during 1841-1844 CE - making the Copenhagen collection of Avestan manuscripts, Europe's largest.

The collection also contains a lithographed book by Kay-Khosrav Shahrokh Kermani: Forugh-e Mazdayasni (Dar al-Khelafeh Printing House, Tehran, 1909 CE), a treatise on Zoroastrianism and Mazdakism in old and modern times as seen from Oriental and Western viewpoints.

|