Contents

|

Suggested prior reading:

Botteh (Paisley) Motif

|

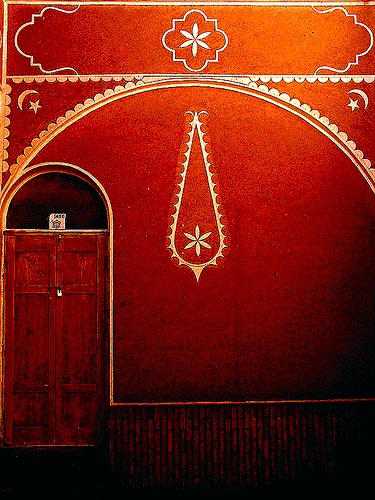

Example of the boteh motif of a termeh fabric

Image credit: Mehdi Vaez |

The design motif known as paisley in the west is taken from the ancient Aryan boteh (botteh) motif. Boteh is a Persian word meaning bush, shrub, a thicket (a small dense forest of small trees or bushes), bramble, herb. Some would even take it to mean a palm leaf, cluster of leaves (perhaps as a repeated pattern) and flower bud. In

Azerbaijan and in Kashmir (in the north of the Indian sub-continent), the name used to describe the motif is buta.

While in recent history, the design is primarily connected to silk and wool termeh fabric and carpets from Yazd and Kerman in Iran as well as woollen scarves from Kashmir, the design can be found in fabric and carpets from throughout the Aryan areas of influence and trade.

Earliest Known Examples

|

Silk Twill with Sassanian royal device (senmurv)

6-7th century CE, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

Dr. Cyrus Parham, in an article published in 1999 in Nashr-e Danesh, vol.16, no. 4, 1378, Tehran, states "We have a multitude of outstanding examples of this motif in the pre-Islamic and Post-Islamic Iranian arts. We find the first manifestations of this ancient motif in Scythian and Achaemenid art, mainly portrayed as the wings of Homa or Senmurv (Simorgh?), and which lasted in the same manner till the Sassanian period (PL.1a)." Regrettably, we cannot locate the Achaemenid and Scythian examples or images cited by Dr. Parham.

Thanks to the dry climate and sandy subsoil of Egypt, fabric could survive for longer periods than in many other regions. It is in Egypt that we find the earliest known samples of silk garments fragments embellished with what appears to be a predecessor of the boteh motif. The fragments date from the 6th-8th centuries CE and discovered in Akhmim a city of Upper Egypt. During the 6th to 8th centuries BCE, Akhmim (also spelt Achmim or Akhmin) a city situated on the banks of the Nile in Upper Egypt, was within the Greek sphere of influence and its Hellenized name was Panopolis, Khemmis or Chemmis. The motif found on the Akhmim fabrics is not found elsewhere in Egypt. For a brief period, Akhmim was under Sassanian control and has on and off been part of the Persian empire since the reign of Darius the Great (522-486 BCE). In all likelihood, Akhmim was at the western end of the Aryan trade roads, the Silk Roads.

The silk fragments discovered in Akhmim's cemeteries at the end of the 19th century CE, are parts of clothing called the paragauda, the border of women's tunics, and the clavus, the paragauda's circular decoration. The word paragauda appears to have Indo-Iranian origins.

The Akhmim motifs appear to be stylized oversized leaves or fruit attached to a tree or vine. The design elements that are consistent with later (unattached) boteh are the pointed dropping tips (aith at times a sprayed tip), and the border around the motif encasing an internal design.

Zoroastrian Connections

|

| "Persian motifs" from Stone p. 236 |

Dr. Cyrus Parham, who we have cited above, states, "In the arts of the final years of the Sassanians, and the early centuries of Islam, we witness certain indications of symbiotic relationship between the cypress and the botteh suggesting that this ancient motif has emerged from the cypress (PL. 1b). From the vantage point of the history of evolution of the botteh, this specimen is quite significant because in spite

of the fact that the emergence of this motif from the cypress is conspicuous in the Iranian works of art of the 17 and 18 centuries (PL. 2), a myriad of art scholars tend to disregard this crucial stage of ornamental and symbolic metamorphosis."

Other articles on the boteh also link the motif to the Cypress and to the significance of the Cypress as a tree of life in Zoroastrian folkloric tradition. In addition, the boteh motif is sometimes referred to as the flame of Zoroaster. We are informed by Fiona Maclachlan that in Azerbaijan, the buta (botteh) is regarded as a symbol of fire.

Different Shapes

There are a variety of different forms of the boteh motif. These different forms could also be related derived shapes and they can sometimes be seen within the same design, be it on fabric, a carpet or an engraving. The fabric fragments from Akhmim display some of the variations.

|

Boteh design variation 1 from Akhmim, Egypt

7 - 8th century CE |

|

Boteh design variation 2 from Akhmim, Egypt

7 - 8th century CE |

|

|

| Bakhtiyari carpet runner c. 1900 CE |

|

| Example of a termeh (traditionally made Iranian fabric) with a the boteh motif |

|

| Other examples of termeh with boteh motifs |

|

Twinned Designs

Flower?

Another variation for the boteh motif is what appears to be a twinned motif that looks like a stylised representation of a blossom. As with the previous variations, this one is also consistent with the variations found in Akhmim, Egypt (see above) from the 7-8th century CE.

|

Column capital at the No Gombad ruins

Balkh, Afghanistan (ninth century) |

|

Twin boteh border design from Akhmim, Egypt

7 - 8th century CE |

|

| Variation of the twin boteh design at No Gombad, Balkh, Afghanistan |

|

|

| Termeh with twinned boteh motifs |

|

| Cut fig fruit - a resemblance? |

|

Related to the Yin-Yang Symbol?

|

Close-up of one of the yin-yang like

motif in the panel to the right |

|

Nishapur (10th century CE) stucco panel containing the yin-yang like motifs

Note that the motifs are in both the upright and horizontal positions |

The motif looks like one half of the yin-yang symbol, a resemblance that has led to speculation about the symbolism behind the motif. However, except for one relatively modern (10th century CE) use of the motif in stucco work from Nishapur presently in Iran's northwest province of Iran, we do not find any other credible examples of the boteh motif used in a yin-yang manner.

The carved stucco panels were excavated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Iranian Expedition from 1935 to 1940, with a final season in 1947. Nishapur was a junction on the Aryan trade roads (also called the Silk Roads). The panels are dated to the Abbasid period of Iranian / Central Asian history, a period that followed the Sassanian era. According to the description at the Met's site, "Among the earliest major finds of the excavations in Nishapur was a building complex that included a domed inner room; a vaulted hall, or iwan; and the courtyard onto which it opened. The lower walls of these areas were decorated with carved and painted stucco dadoes of lively and beautiful design, and at least some of the upper walls were polychrome-painted on a smooth whitewash coating over walls" and, "Carved stucco decoration, perennially important in Iranian architecture, is most notably represented by the reconstruction of a small iwan, or hall, of the tenth century (from the mound called Sabz Pushan), whose dadoes must have given an even more sumptuous visual effect before the loss of their polychrome painting."

|

| A Kashmiri bota shawl |

Kashmiri Buta

The earliest surviving examples of the boteh motif in the weavings of Kashmir, are from the third quarter of the 15 century CE. reportedly commissioned by Sultan Zein-al-Aabedin (d. 1468). This Sultan is the one who, according to Kashmiri historians, geographers and researchers, brought the “decorative designs from Iran to India.” The motif has since become a very popular theme of Kashmiri woollen scarves.

» Offsite reading at TextileAsArt.com

Paisley

|

Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland with the previous Anchor thread mill (one of the

largest in the world) in the

foreground.

Image credit:

Robert Orr at Flickr |

|

A preserved loom at a weaver's cottage in Kilbarchan close to Paisley.

At one time there were 900 looms in Kilbarchan

Image credit:

The Beckett Blog |

The western name for the boteh motif is taken from Paisley, a town in western Scotland not too far from Glasgow, which had once specialized in the production of scarves and shawls (from the Persian word shal) decorated with the boteh motif.

In the first half of the 17th century CE, the British East India Company introduced boteh shawls other fabric articles made in Kashmir to Europe. Kashmir was a northern Indian kingdom. The imports from Kashmir, especially the women's shawls, became popular throughout Europe, and soon, demand outstripped supply. European weavers in France, England and Holland took advantage of the demand to produce imitations. European hand weaving technology, however, was less sophisticated than the age old hand-weaving techniques of Persia and Kashmir, and the number of colours in the European weave was initially limited to two. While local manufacture made fabrics with the boteh design more accessible in Europe, the original Kashmiri and Persian fabrics commanded a premium in price because of their beauty and superior quality.

Britain took the lead in manufacturing imitation fabrics - especially women's shawls - using the boteh design, when in 1790 and 1792 hand weavers in Edinburgh and Norwich began to reproduce the Kashmir and Persian shawls. Weavers in the town of Paisley joined this growing industry in 1805. In 1812, the Paisley weavers introduced an attachment to their handlooms that enabled them to use five different colours of yarn. This innovation gave the Paisley weavers a competitive edge over weavers elsewhere who were only using two colours, commonly indigo and madder. The Paisley weavers also took special care to imitate the Kashmiri shawls as closely as possible. In order to copy the latest Kashmiri shawl designs, agents from Paisley travelled to London where the Kashmiri shawls were arriving by sea. Within eight days of the arrival of a batch of Kashmiri shawls from India, Paisley imitations were being sold in London for £12 while the original Kashmiri shawls were selling for between £70 and £100.

It wasn't long before the name Paisley became synonymous with the boteh motif and demand for the imitation shawls grew as women all over Britain began to ask for 'Paisleys'. The weavers of Paisley developed a much sought after skill and at the peak of demand of their shawls they became the most highly-paid and well-educated workforce in the country. The high wages attracted more apprentices and at one point in the number of skilled weavers in Paisley numbered 6,000. The weavers worked out of their cottages or in loom-shops holding four to six looms. Paisley had a thriving cottage industry of weavers. Unfortunately, this boom would be short-lived.

With the introduction of semi-automated Jacquard looms in the the 1800s, Europeans gained the ability to mechanically weave fabrics with up to five colors. In addition, shawls could be woven in one piece with bolder designs. The Jacquard loom which used punched cards instead of a drawboy was introduced to Paisley in the 1820’s. The drawboy pulled the ropes controlling the overhead harness on the loom when the weaver would called out his instructions. While this development of the Jacquard loom produced a more error free fabric, it also reduced the manpower needed to operate a loom which became larger and more expensive. The development changed what was a cottage industry into a factory based one and the workers were given specific tasks and had to develop a different skill set. Now there was a division of labour and workers had to have specialized skills. By 1860, the Paisley factories were able to produce shawls with up to fifteen colors, but that number was still only a quarter of the colours in some Kashmiri shawls.

Yet another development would hasten the decline of the woven shawl industry in Paisley - fabric printing. The printing of designs onto a fabric - rather than weaving the design - decreased the cost of producing fabric designs. By the 1860s, most hand weavers including those in Paisley, were living in poverty. Many migrated to Canada and Australia.

Through the rise and fall of Paisley's fortunes, hand-woven Kashmiri shawls continued to be synonymous with high quality, many becoming a part of a family's heirloom. At the peak of their popularity, the cost of a high quality Kashmiri shawl in Britain was equivalent to the price of a small house. The East India Company continued to sell them at twice-yearly shawl sales in London.

Suggested additional reading:

» Top

|