Contents

|

The Wall of Gorgan

|

Aerial view of the wall running through the country

Note square embankment (a military fortified outpost?)

in the foreground. Image credit: Gorgan Wall

|

Suggested prior reading:

Related reading:

Location and Purpose

The Wall of Gorgan was a defensive wall built some two thousand years ago (and perhaps earlier) to form a barrier to stop - or at least hinder - northern raiding parties from pillaging ancient Varkana, the land that later came to be known as Gorgan - today's Golestan Province of Iran.

Sometimes called the Great Wall of Gorgan or the Sassanian Wall (and incorrectly, the Wall of Alexander), the Wall of Gorgan is also known locally as Sadd-e Anushirvan and Sadd-e Piruz (meaning the Anooshirvan or Firooz Barrier). To the local Turkoman population it is known as Qizil Yilan.

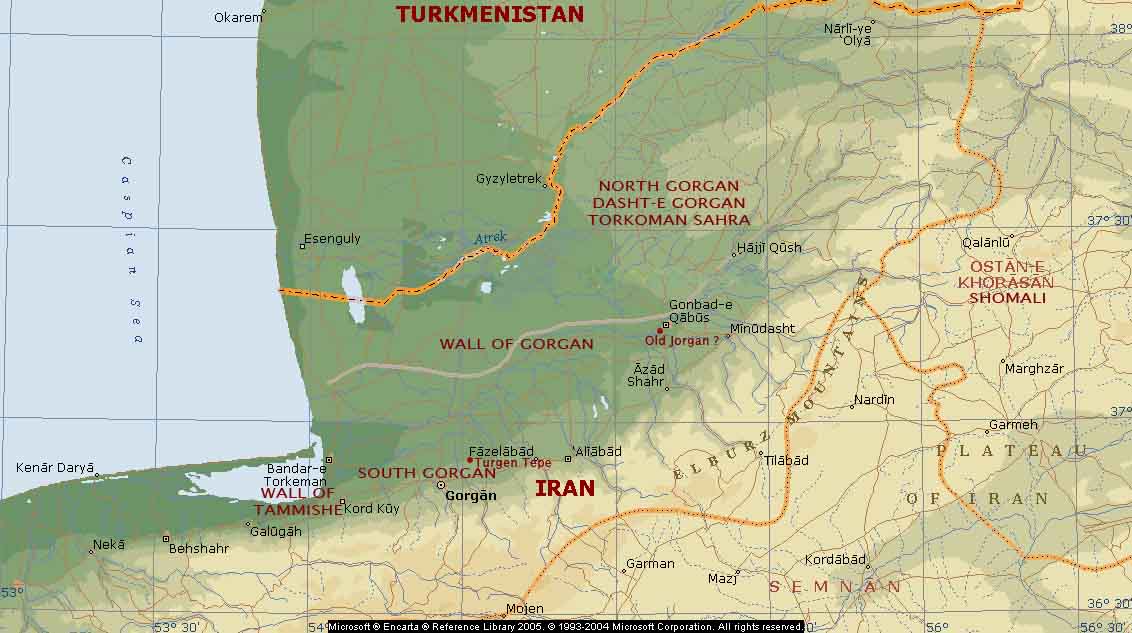

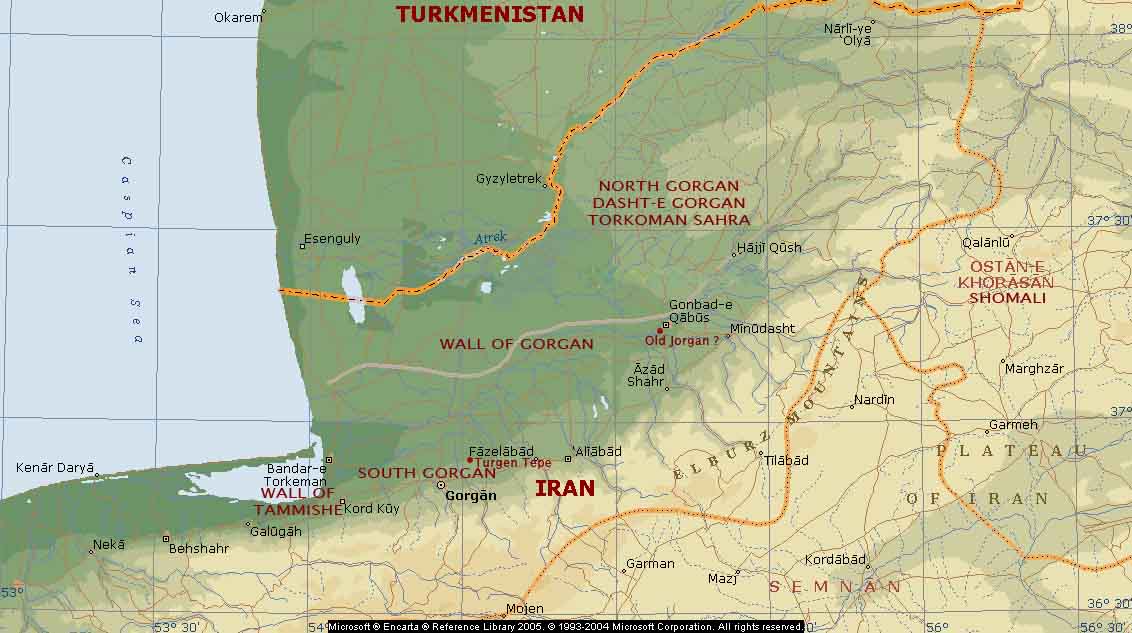

The wall runs for about 195 km from the Caspian Coast in the west to the Pishkamar Mountains in the east. The wall was a second barrier for raiding parties from the north, the first being the Atrek river which formed the natural boundary between Dahistan to the north of the river and Varkana to the south. The wall runs just north of the Gorgan River.

As we have noted in our main page on Varkana / Gorgan, the region was known as Varkana during the Achaemenian era (c 650-330 BCE). Yet earlier, it was known as Vehrkana in the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta. Vehrkana was the ninth nation in the Avestan Book of Vendidad's list of nations.

While the red brick used in the construction of the wall is dated to the the Sassanian era, the brick-work could be renovation of an existing wall dating perhaps to Parthian times. We further discuss the dating of the wall below.

The district the wall through which the wall runs is fertile, and in some places spectacularly beautiful and picturesque.

|

Map of the Gorgan region. The gray line running east-west just north of Gonbad-e Qabus is the wall of Gorgan.

The area to the north of the line is called the Dasht-e Gorgan, the semi-arid Plains of Gorgan. Image credit: Microsoft Encarta. Notations by K. E. Eduljee

|

Interesting Facts About the Wall

- The wall is also known as the Red Snake because of its red-brick colour.

- The wall was 195 km long, 180 km of which is still survives today, though in a very poor condition.

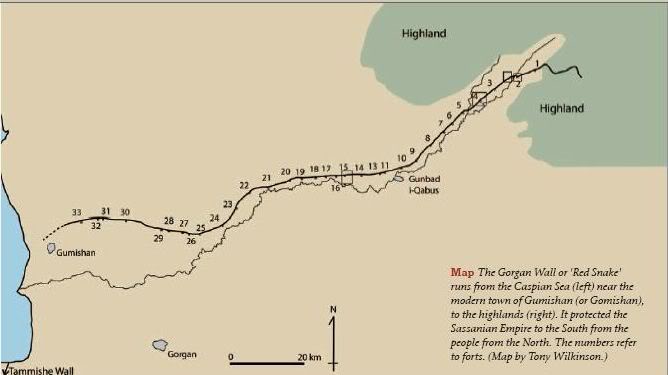

- The wall runs west to east from the the Caspian Sea coast near the town of Gumishan / Gomishan, skirts around the north of Gonbad-e Kavous and disappears in the Pishkamar Mountains that stand at the junction of the Elburz and Kopet Dag mountains.

- There is a second smaller wall of the same age called the Wall of Tammishe at the western end of the province (see the maps) and near Bandar-e Gaz.

- Part of the western end of the Tammishe wall is submerged under the Caspian Sea

- It is over 3 times the length of Hadrian's Wall in northern England

- According to the Science Daily News (February 26, 2008), "The wall longer than Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall put together."

- As noted in the map to the right, attached to the wall as some 33 forts.

- Some writers postulate that the Caspian Gates mentioned by Greek writers could originally have referred to a gate in the Wall of Gorgan.

- According to the Science Daily News (February 26, 2008), "The 'Great Wall of Gorgan' in north-eastern Iran, a barrier of awesome scale and sophistication, including over 30 military forts, an aqueduct, and water channels along its route."

|

| Aerial view of a fort (top right) along the Gorgan Wall. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

|

| Garkaz (earthen) Dam excavation. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

|

| Close-up of the brick wall. Image credit: Anonymous at Kosmix |

|

| Excavations of a brick kiln's ruins near the Gorgan Wall. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

The Wall's Use as a Defensive Shield

The wall can be thought of as a one walled fortress, and the over 30 forts along its length can be thought of as the wall's towers. The manner in which the forts were placed along the wall can be seen in the aerial image on the right. Additional forts were also constructed and placed between one and two kilometers behind the wall.

The authors of The Enigma of the Red Snake at Current Archaeology ask, "How many soldiers guarded the Persian Empire's most elaborate military barrier? If we assumed that the forts were occupied as densely as those on Hadrian's Wall, then the garrison on the Gorgan Wall would have been in the order of 30,000 men." Another estimate based on the room sizes in the forts place the garrison at between 15,000 and 36,000 soldiers.

|

| Garkaz Dam site along the Gogan River (Gorgan-Rood). Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

Wall as Part of a Large & Sophisticated Water Supply System

The wall was more than a defensive wall, it was also part as a large and sophisticated water supply and irrigation network. Durham University's Archaeological Project states, "Discoveries by our Iranian colleagues, now confirmed by fieldwork in 2005, demonstrate that the wall is associated with a massive system of water supply consisting of earthen dams and canals. A canal, 5m deep or more, conducted water along most of the Wall. Its continuous gradient, designed to ensure regular water flow, bears witness to the skills of the land-surveyors responsible for marking out the Wall's route."

Construction of the Wall - The Red Snake

In the absence of stone for constructing the wall, bricks were used giving the wall it its characteristic red colour and its nickname - the Red Snake. The soil beside the wall was particularly suited for the making of baked bricks and brick kilns were built beside the wall all along its length. The kilns lined the wall sometimes a hundred meters apart and sometimes less than forty meters apart. In all, the kilns numbered in the thousands and produced a staggering number of fired bricks - in the millions, each to a standardized size: 37cm length in the west section of the wall, 40cm length in the east section of the wal. Each brick was between 8cm to 11cm in thickness.

Dating the Wall

Iranian archaeologist Dr. M. Y. Kiani, who led the archaeological team in 1971, is cited in Encyclopaedia Iranica as concluding through carbon dating, that the wall was initially built during the Parthian dynasty (247 BCE to 229 CE) - around the same time period as the early construction of the Great Wall of China. Kiani further concludes that the wall was restored during the Sassanid era (3-7th cent. CE).

However, Current Archaeology* reports, "The OSL and radiocarbon samples demonstrated conclusively(?) that both walls had been built in the 5th or, possibly, 6th century CE." The authors go on to say, "We know that the (Sassanian) Persian king Peroz (459-484 CE), when campaigning against the White Huns, spent time repeatedly at ancient Gorgan (next to modern Gonbad-e Kavus, the site of our base camp just south of the Wall). Eventually he had to pay with his life for venturing into the lands of the White Huns." We do not know how Dr. M. Y. Kiani came to his conclusions that the original wall was built in Parthian times and renovated in Sassanian times, but it stands as a possibility.

We note that the categorical statement made in Current Archaeology (cited above) about the date of the wall is based on the date of some brick samples taken from the wall. We do not know how the archaeologists managed to make their sampling (out of the millions of bricks used to construct the wall) statistically significant enough to produce such certainty. Even if the sampling was executed in a manner to give statistically significant results, the authors may have the data to conclude that the bricks samples date back to Sassanian times, but we see no data to support the date for the construction of the wall itself. While it is possible that the wall itself was built at the same time the bricks were manufactured, there are other possibilities as well. The bricks could have been used to renovate, rebuild or strengthen an existing wall. The wall in itself could have been built over an existing wall, and a previous wall built of earth could simply have eroded away. The campaigns of Sassanian king Peroz against the "White Huns" are just some of the records that have come down to us about the security problems faced by the people of Varkana-Gorgan. There is nothing in that report to suggest that Peroz built the wall, which is the implication of adding this piece of information. While these are all possibilities we cannot extrapolate the possibility to an absolute certainty.

*Authors: Hamid Omrani Rekavandi (ICHTO), Eberhard Sauer (University of Edinburgh), Tony Wilkinson (University of Durham) and Jebrael Nokandeh (ICHTO & University of Berlin)

Herein lies the problem with results produced by some archaeologists. There deductive reasoning is often poorly supported and reasoned. Too often, categorical statements are made on the basis of possibilities, theories and even hunches.

Archaeological Explorations

An archaeological team headed by Dr. M. Y. Kiani began exploration work on the wall in 1971. With change of governments, we assume that excavation work was interrupted.

Then in 1999, during construction of the Golestan Dam and its irrigation canals, workers came across the ruins of the wall while digging a canal. A team of Iranian archaeologists under the direction of Jebrael Nokandeh were charged with exploring the ruins. Later, in 2005 explorations began to be conducted by a joint Iranian and British team. The British team included archaeologists from the Universities of Edinburgh and Durham.

The teams found the ruins in very poor condition. Urban and agricultural development had encroached on sections of the wall, and the presence of these developments caused difficulties and delays for the team.

|

| Close-up of excavation site at Qareh Deeb. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

|

|

| A section of the Gorgan Wall in the hills. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

|

| Section of the Gorgan Wall and a water network ditch in the plains. Image credit: Arman Ershadi |

|

» Top

Suggested prior reading:

Related reading:

|