Image credit: Savasir at Flickr

ContentsBehistun |

» Site Contents |

Related reading:

» Darius I, the Great

» Old Persian Language

Site Description, Contents, Location

|

| Map showing Kermanshah province in northwest, modern Iran (shaded green). Base image credit:Wikipedia |

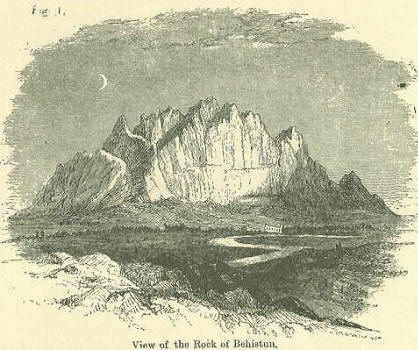

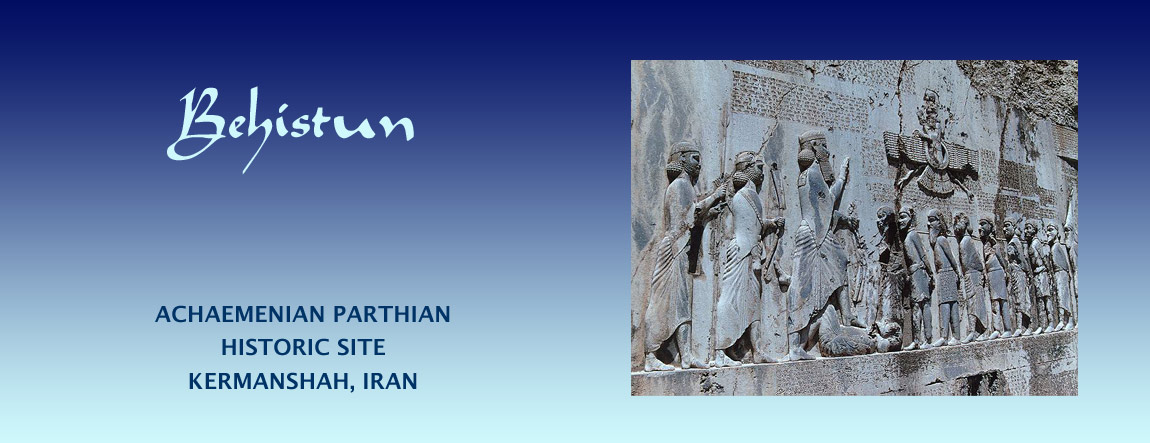

The Behistun (also spelt Bisotoun, Bistoon, Bisitun, Bisutun) Historic Site is located in the northwest Iranian province of Kermanshah on a branch of the Aryan Trade Roads (also called the Silk Roads), a portion of which became the Royal Road of Darius I, the Great.

Within the site is Mount Behistun along whose side is carved the famous rock relief of Darius. The branch of the Aryan trade roads that passes below Mount Behistun runs between Ekbatana / Hamadan and Kermanshah city. Across the road from the monument is a caravanserai.

The historic site covers 116 hectares and has located within it sixteen historical monuments. Some of these monuments include the Darius reliefs and inscriptions that can be seen towering above the base of Mount Behistun. The site became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.

According to George Rawlinson in his book The Seven Great Monarchies, Vol. 3, Media, "This remarkable spot, lying on the direct route between Babylon and Ecbatana, and presenting the unusual combination of a copious fountain, a rich plain, and a rock suitable for sculptures, must have early attracted the attention of the great monarchs who marched their armies through the Zagros range, as a place where they might conveniently set up memorials of their exploits."

|

Site Name

In 1835,Sir Henry Rawlinson, an officer of the British East India Company army, began to investigate the monument near the village of Bisutun (also spelt Bisotoun, Bistoon, Bisitun, Bisutun). He named the inscriptions, the 'Behistun Inscription', his anglicized version of the village's name. Diodorus Siculus (c. 1st century BCE) writes about 'Bagistanon' a name that appears to be derived from the Old Persian Bagastan, meaning the Land of God.

|

Stories Surrounding Behistun

The following accounts regarding Behistun are a good indicator of the credibility of ancient writers when they relate events that happened before their lifetime. There is some recollection of the facts and an abundance of conjecture.

Around 400 BCE, Ctesias, a Greek physician and historian from Cnidus in Caria and who was physician to Artaxerxes Mnemon whom he accompanied in 401 BC on Artaxerxes' expedition against his brother Cyrus the Younger, noted the existence of the monument and also made mention of a well and a garden beneath the inscription. He, however, incorrectly concluded that the monument had been dedicated "by Queen Semiramis (a legendary Assyrian warrior queen associated with Ninus, eponymous founder of Nineveh) of Babylon to Zeus".

Diodorus Siculus (c. 1st century BCE) writes about 'Bagistanon' (a reference which gives us a clue about the original name), but continues to believe the claim that the rock-face was inscribed by Semiramis.

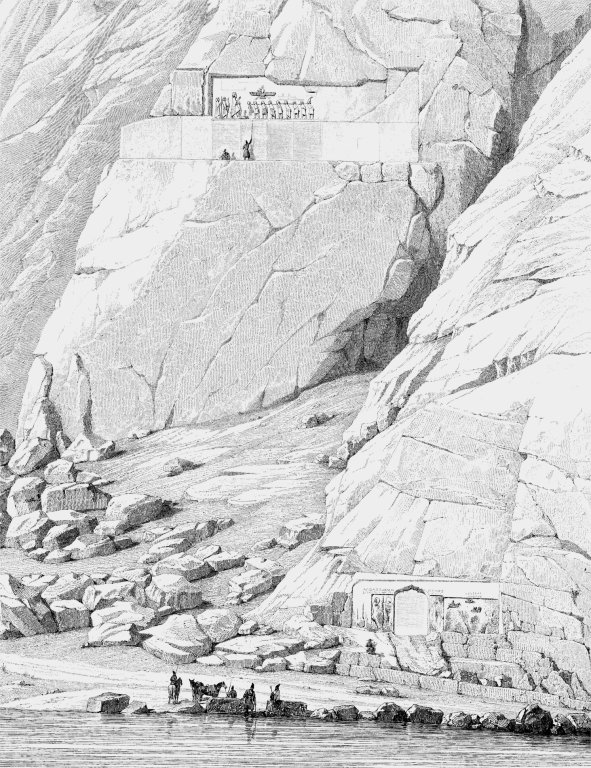

Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius Tacitus (56 - 117 CE) also mentions the Behistun site and includes a description of some of the long-lost ancillary monuments at the base of the cliff, including an altar to 'Herakles'. Objects that have since been recovered, including a rock figure dated to 148 BCE, are consistent with Tacitus's description.

The local Persians, in medieval times had forgotten about Darius. Instead of being attributing the monument to Darius I, the Great, they thought it was the work of Khosrow II - one of the last Sassanid Kings (who lived over 1000 years after the time of Darius I).

Another local legend involving Mount Behistun (Bisotoun), is recounted by Ferdowsi in his Shahnameh (Book of Kings) circa 1000 CE. The legend is about Farhad, who was a lover of Khosrow' wife, Shirin. The legend states that, exiled for his transgression, Farhad was given the task of cutting away the mountain to find water. If he succeeded, Khosrow would give him permission to marry Shirin. After many years and the removal of half the mountain, he did find water, but was falsely informed by Khosrow that Shirin had died. Deranged, Farhad threw his axe down the hill, kissed the ground and died. The axe was made from pomegranate wood, and at the spot where the axe where fell, a pomegranate tree grew with fruit that would cure all ill. Shirin on hearing the new went into deep mourning.

|

| View of the valley from Behistun (Bisotun) with a caravanserai in the foreground. Behistun lies on a branch of the Aryan trade road running between Ecbatana / Hamadan to Kermanshah and westward to Baghdad and Mesopotamia Image credit: Ensie & Matthias at Flickr. |

Inscriptions of Darius I, the Great

Size & Situation

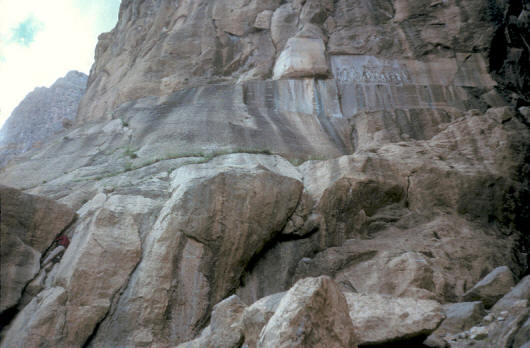

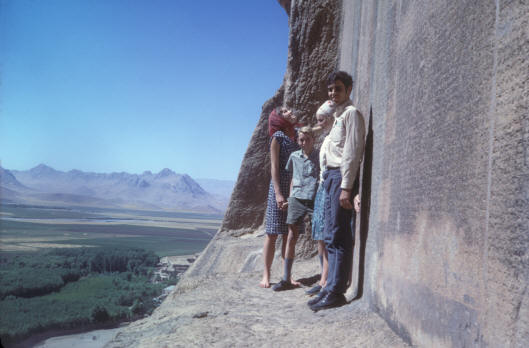

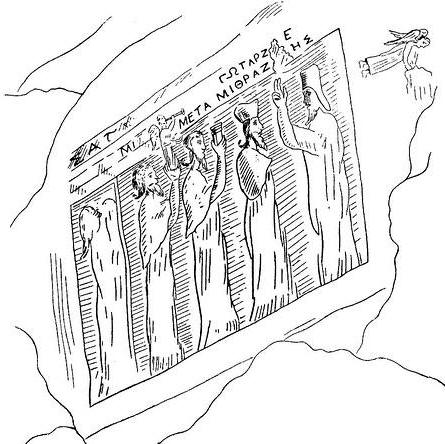

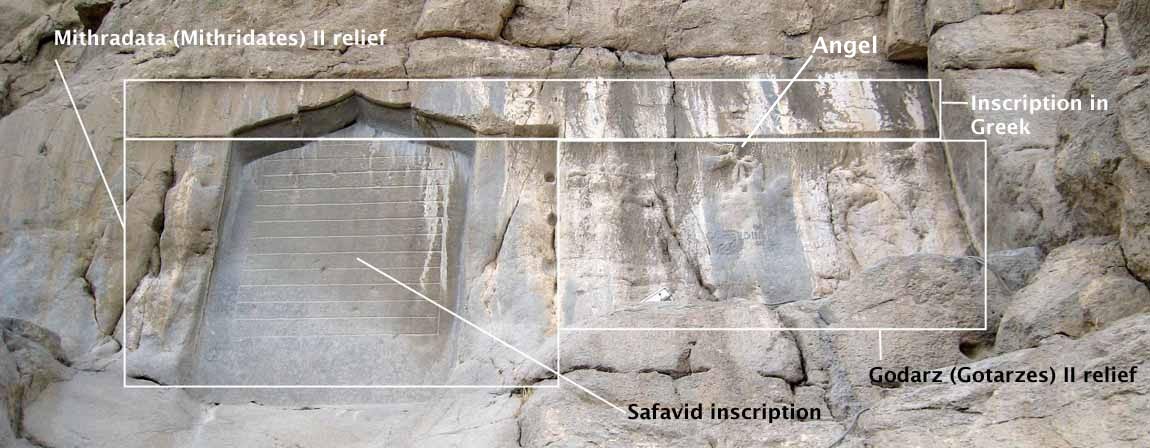

The principle rock relief and accompanying inscriptions at Behistun are those commissioned by Darius I, the Great (522-486 BCE). The reliefs and inscriptions which are a hundred metres above ground level on a limestone cliff, are approximately 15 metres high by 25 metres wide in size.

Content

The relief and inscriptions chronicle for the main part the court intrigue and rebellions that Darius had to contend with in his ascension to the throne and the many rebellions that broke out all across the Persian empire shortly after he assumed the throne.

Languages

The inscriptions have the same text written in three languages, Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, using the cuneiform script, causing some to call the Behistun inscriptions the Persian Rosetta Stone - the 196 BCE Rosetta Stone being the ancient Egyptian stone inscriptions of a passage in three scripts: two in Egyptian language hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts, and one in Classical Greek. Babylonian, one the languages used in the Behistun inscriptions, is a later form of Akkadian and the inscriptions helped to increase our understanding of Babylonian and thereby Akkadian. Indeed, the cross references help to provide a better understanding of all the languages employed in the inscription.

Darius mentions in the inscriptions at Behistun that he had copies of the inscription written on parchment and distributed throughout the empire. A copy of the inscription written in Aramaic has indeed been found on the island of Elephantine on the upper Nile near the city of Aswan in Egypt.

Organization

The Old Persian text consists of 414 lines of text placed in five columns. The Elamite text consists of 593 lines of text placed in eight columns, while the Babylonian text consists of 112 lines.

Figures

The figures in the rock carvings are identified by inscriptions next to them.

Facing the king, are nine men tied together with a rope around their necks and their hands tied behind their backs. They

are rebels defeated by Darius and identified (from closest to Darius to the farthest) as: Achina the Elamite, Nidintu-Bel the Babylonian,

Martiya the Elamite, Fravartish (Phraortes) the Mede, Cisantakhma (Tritantaechmes) the Sagartian,

Frada the Margian (Margush), Vahyazdata the Persian (another individual who claimed to be Bardiya/Smerdis), Arakha the Armenian, and Skunkha the Saka.

The noblemen behind Darius are two of his six co-conspirators, Vidafarna (Intaphrenes, carrying a bow) and Gaubaruva (Gobryas, holding a lance). The king's lance carrier was one of the most important court titles and positions. The same can be assumed for the bow carrier.

One of the priosoners appears to have been added after the others were completed. Darius' beard was either repaired or also added at a later date since it is carved on a separate block of stone and attached to the main relief with iron pins and lead.

|

| King Darius I, the Great with the rebels paraded before him. Image credit: Dynamosquito at Flickr |

|

|

| Parthian King Valgash (Vologese) standing before an altar. On the altar is an inscription identifying the king. |

|

| Balash Stone with carved reliefs on three sides Image credit: Dynamosquito at Flickr |

|

| Parthian era bas relief at the base of Behistun historic site. Image credit: Wikimedia |

|

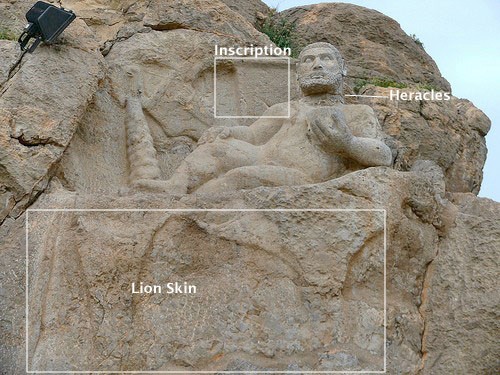

| Selucid era carving of the Greek god Heracles |

Seleucid Era Statue of Heracles

According to its seven lines of inscription in old Greek, the statue was carved in 139 BCE on the occasion of the victory of Demetrius II Nicator, a Seleucid Greek, over the Parthian king Mithradata I (Mithridates I) - and then opportunistically changed to commemorate the defeat of the Seleucids.

[After the defeat of the Achaemenid Persian Empire following the Macedonian invasion, and following Alexander's death, a general of Alexander, Seleukos / Seleucid, established the Greek Seleucid dynasty.]

The statue represent the Greek god Heracles who is the Greek counterpart of the Roman god Hercules. In Greek mythology, Heracles is the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and great-grandson (and half-brother) of Perseus. He was the greatest of the mythical Greek heroes, a paragon of masculinity, and ancestor of royal clans. Some authors suggest that in ruling circles, a form of religious syncretism occurred amongst those associated with, or influenced by, the Seleucids, and that Heracles is an anthropomorphized version of the legendary Iranian Verethragna (Bahram), meaning victorious. The dual representation enabled Iranians to relate to Greek worship practices.

Heracles is depicted resting on a lion skin. Beside him is an olive tree with a quiver full of arrows is hanging from it. Nearby stands a club leaning against the rock.

Related reading:

» Darius I, the Great

» Old Persian Language

Offsite reading:

» Full translation of the Behistun Inscription at Wikipedia

» The Behistun Inscription at Mark Drury's site

» Behistun (Bisitun) Monument at Bruce J. Butterfield's site

» The Behistun Inscription at Bruce J. Butterfield's site

» The Behistun Inscription at Livius

» The Behistun Inscription at ICS

» Travels in Persia 1673-1677 Book Two by Sir John Chardin