Contents

|

Suggested prior reading:

What is Termeh?

|

| An example of termeh articles. Image credit: Wikipedia |

Termeh is the name given to a specialty cloth that originated in Yazd. Traditionally, the cloth was hand-woven using natural silk (Persian, ابریشم abrisham) and wool fibre (Persian, پشم pashm). Termeh can take the form of fabric, sheets, panels and other shapes.

Good quality traditional termehs are part of a family's heirloom in much the same way as are (the related) Kashmiri scarves. They are often an article used in Iranian weddings - such as the sofreh used as a floor spread sheet. In these type of termehs, gold and silver threads may be incorporated either into the weave, as part of an embroidered pattern or as a border.

Both Yazd and neighbouring Kerman regions have the reputation of producing quality termeh. As is the case with Persian carpets, traditional Yazdi, as well as Kermani termeh, have a reputation of being of superior quality and workmanship. Yazdi and Kermani termeh were traded throughout the Aryan trade regions, that is along what came to be known as the Silk Roads.

Termeh and Aryan Trade

Marco Polo, travelling the Aryan trade roads (called the Silk Roads) passed through Yazd in 1272 CE. He arrived in Yazd at about the time that Zoroastrians had been reduced to a minority in their ancestral lands. Nevertheless, Zoroastrians would still have asserted but who would have still asserted a considerable presence. Polo described the city as good and noble, and took remarked that city was noted for its silk production.

"Yazd also is properly in Persia; it is a good and noble city, and has a great amount of trade. They weave there quantities of a certain silk tissue known as Yazdi, which merchants carry into many quarters to dispose of."

In ancient times, Yazd and Kerman were silk and wool textile manufacturing centres together with Kashmir in the northern Indian subcontinent and the Fergana valley (presently in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan). Yazdi silk designs do share some similarities with Fergana silks and Kermani scarves competed with Kashmiri scarves. It is quite possible that local merchants and traders based in one of these areas acquired samples made in the other area and asked local artisans to weave a similar design and fabric.

Termeh Products

Nowadays, the more expensive termehs are usually spreads called sofrehs (floor spread sheets or table-cloths), say about 150 cm. (five feet) square. Other termeh products are scarves, cushion covers and mats. However, at one point in time, termehs were also used to produce curtains, garments, quilt covers, cummerbunds (Persian kammar-band meaning waist bands), robes and even royal headdress such as turbans.

Assessing the Value of Termeh Products

A termeh's value is based on the following:

- The fineness and quality of the fibre and thread;

- The incorporation of gold and silver dramatically increases the value;

- The number of coloured threads used in the weaving. The greater the number of colours, the greater the value. Elaborate termehs can have two to three hundred different coloured threads;

- The number of layers that constitute the fabric, the large number increasing the value;

- The addition of a border and wider borders;

- Fine woven designs usually add more value than embroidered designs. Intricately embroidered designs called sermeh doozy. Printed designs add the least value;

- The uniqueness of the design;

- Lining the fabric. Lining normally adds to the value;

Termeh Patterns

|

| Yazdi Zartoshti-doozy (needle-work) patterns. Image credit: Berasad |

One of the most common design motifs associated with the termeh is the boteh (also spelt botteh) motif known in the west as the paisley design. The history of the boteh motif, termehs (and indeed Persian carpets as well) and Aryan trade are closely linked.

The design for tablecloths may include a chequered or honey-comb pattern. Other design patterns include stripes, both wide and narrow, the Atabaki pattern, and the Zomorrodi pattern that was predominantly green in colour.

Image patterns popular with Yazdi Zartoshti women who engage in Zartoshti-doozy (Zoroastrian needle-work / embroidery) include the tree of life, the cypress tree, the juniper tree, clove, four or eight petal jujube, peacocks, roosters, hens and chicks, hoopoe, fish and geometric shapes such as circles and squares.

Stripped Patterns

Termehs with a multi-coloured stripped patterns are associated with Zoroastrian folk designs used for women's pantaloons, as well as with Kermani scarves. The stripes patterns are both narrow and wide, subdued in tone and quite colourful. Examples are shown in the images below.

|

|

Kermani Shawl with a stripped design

Image credit: Afshar |

|

|

An antique (third quarter of the nineteenth century) embroidered silk panel from Yazd

that originally would have formed the knee to ankle section of one trouser leg, of a shalvar (pantaloon)

from a Zoroastrian woman's wedding costume (see portrait below). Photo credit: O'Connell Guide |

| Kermani Shawls

|

Kermani Pateh-Duzi Embroidery. Wool on wool shawl with saffron background.

Mid 19th Century, 78 x 78in, 189 x 189cm. Image credit: TextileAsArt |

|

Antique Kermani woven shawl c 1750 CE

The shawl was fragment and reconstituted from several pieces.

Image credit: Eccentric Wefts |

The examples shown here in the images above and to the right are those of woven (above) and embroidered (right) shawls of Kerman.

The pateh-doozy / pateh-duzi or embroidered shawl of Kerman is made using a background material known as shal, a word that became 'shawl' in English. The shawl is often woven using a twill weave and the most common colour of the base fabric is red - though as we see in the images here, a variety of other colours are used. The pattern for the shawl is embroidered on the base fabric, the design for which is pounced over the surface of the fabric using carbon (coal dust) dusted over perforated parchment. The carbon dust outline is further defined by a pen. Some embroiderers developed the technique of following the texture of the twill weave with their embroidery producing a patterned shawl that could easily be mistaken for a more expensive woven shawl.

A type of intricately embroidered fine shawl is the aksi meaning 'reflection'. Here, even though the the pattern is embroidered on one side, by splitting the warp thread into half, a 'reflective' image is produced on the other side of the shawl.

As with the weavers, expert embroiderers are a vanishing breed. Today, a few surviving Kermani embroiderers can be found in the Kermani village of Hudk.

Heritage in Peril

|

Traditional Zoroastrian Yazdi wedding costume.

Note stripped shalvar (pantaloon).

See shalvar panel above. Image credit:

A Zoroastrian Tapestry Art Religion and Culture

by Pheroza J Godrej and Firoza Punthakey Mistree.

(Also see note* to the left)

|

|

|

Clothes made from termeh

Qajar Dynasty era painting

Image credit: Parima

|

|

Manufacturing termeh was a cottage industry. The looms would have been located in individual homes and each member of the family likely had a role. The construction of the looms, the method of making thread, the designs and patterns, and the vibrancy of the colours produced by different dyes, would have all been family secrets.

This rich heritage is now in peril. The a piece or sheet of fabric can take days if not months to produce. The expense of this labour intensive craft cannot be adequately compensated by the prices realized. Once a family stops the tradition of weaving, their knowledge, skills and trade secrets will be lost forever. Without rich patrons, the craft will die out.

The bazaars of Yazd used to be filled with artisans with different sections of the bazaar allocated to different trades and crafts. For instance, the zargari or goldsmith section, the kashigari or tile working section, the chit-sazi or chintz-making section, and the mesgari or copper-smith section.

In the days of yore, traders from around the world came to the bazaars in this oasis town and carried the creation of Yazdi ingenuity throughout the known world. The craft shops are now being replaced by shops selling electronic wares. The journals of many a returning traveller are filled with the lament that they are, within the span of their own generation, witnessing the demise of a heritage - a heritage that once lost will never be revived, for the knowledge and skills of these crafts will die with the crafts-women and men. The reports tell us that the art of producing hand-crafted termeh today survives in but a few centres.

[* Note: The image to the right titled "Traditional Zoroastrian Yazdi wedding costume" is part of an article by Firoza Punthakey Mistree titled "Hues of Madder Pomegranate and Saffron Traditional Costumes of Yazd" at p. 553. The photographer for the image was Gautam Rajadyaksha and the model, Meher Jesia. Also see the image titled "A modern gara with a matching blouse" at our page on The Gara Sari, in the section, The Modern Gara].

Termeh Production

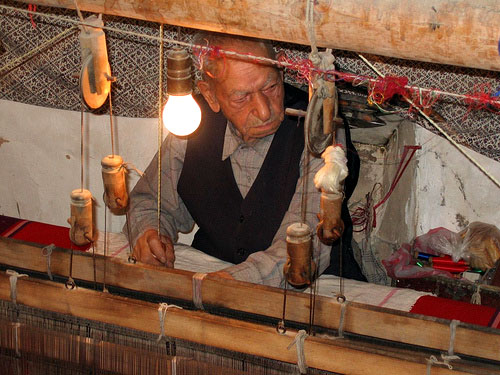

Producing termeh requires two different skill sets, the first being product and design and the second weaving. The weaver is called the Goushvareh-kesh. One weaver might be able to combine the different skill sets, perhaps say in folk weaving, but as the product becomes more sophisticated, two or more individuals need to work as a team to produce termeh. Weaving intricate designs is a slow process with, in some cases, only 25 to 30 centimetres of fabric woven in a day.

Dyes

One of the most common background colours for a termeh is red, and the different shades of red that the artisans of Yazd and Kerman can produce are quite astounding. Traditionally, the dyes are all from natural sources, usually a vegetable source. For instance, one of the base red colours is called jujube red. Jujube is sometimes called a red date (not to be confused with dates from a date palm). Other common background colors which are used in termeh are green, orange and black.

Wool Termeh Handloom Techniques of Yazd and Kerman

The first step in the process of making a wool termeh, say a woollen shawl, is the collection of the wool that will be spun and woven or knitted into fabric. The finest wool is that which is combed or sheared from underbelly of goats. The next step is grading and sorting. Different colours of wool are also matched and batched separately. The sorted raw wool is cleaned of dirt and debris.

The production starts with the spinning the wool followed by the dyeing process. The dyer, the person looking after the dying of the wool, will have prepared the colours to be used according to samples provided to her or him. The art of natural dyeing has been developed over the ages and is often a closely guarded secret. Many dyers will know how to formulate some three hundred shades.

A pre-weaving expert or group of expert specialists then work on the wool before the weaving process can start. The different specialist tasks are warp-making, warp-dressing, wrap-threading, pattern-drawing, colouring and pattern-writing.

The pattern guide is the coded pattern guide and instructions for the colourist and weaver sometimes written in a form of shorthand or code. This process of annotating the designs so that each stitch is written down permits the reproduction of the most intricate patterns employing an extraordinarily wide range of colours.

The warp is the set of lengthwise yarns that run up and down the loom. The warp yarns are fully attached before weaving begins. The weft is the yarn that the weaver weaves back and forth and in-between the warp to make fabric.

During wrap-making the worker twists the two to three thousand threads warp threads to the required thickness. To illustrate the number of warp threads and heddles employed during weaving, a hand-woven tea-towel has between 300 and 400 warp threads.

Warp-dressing is stretching the wrap threads so that they can sustain the strain of the weaving process and the constant pressure and movement of the heddle. A heddle separates the warp yarn for the passage of the weft yarn. A typical heddle is made of cord or wire suspended from the top shaft of the loom. Each heddle has an eye in the center through which the warp is threaded. There is a heddle for each thread of the warp, and as such there can be, say, a thousand heddles for fine or wide warps.

Warp-threading is the passing the yarn through the heddles.

After the wrap assembly is prepared, if the fabric is to have a pattern, pattern-drawing is the drawing of the pattern design.

Colouring is the colouring of the drawing including the matching of different shades using a colour card based on the annotated drawing.

When the weaving process starts, the weaver if assisted by, say, two or three apprentices, calls out the colours to be used according to the pattern guide.

For the weaving the pattern portions, the weft shuttles are replaced by fine needle-like spools. The spools are made of fine light wood with sharp edges on both sides charred to prevent them becoming rough or jagged during use. The pattern's design is produced on the underside of the wrap with the weaver inserted the spools from above. After a line of multiple wefts is completed, a comb was pulled down towards the weaver with it teeth running through the warp thereby pushing and compacting the weft into a tight weave.

If the fabric being produced - in our example a shawl - has complicated patterns, the weaving can be divided between up to ten looms, each working on a particular section of the shawl. After the different sections are woven, they are handed over to a specialist will repair any defects and join the pieces together in a manner that the joints are not be visible.

Silk Production Elsewhere in Iran

In addition to Yazd and Kerman, the other centres of silk production in Iran that were involved with silk trade along the Aryan trade roads were Gilan, Mazandaran, Khorasan, Isfahan, and Kashan. During Sassanian times, the production could have reached 3,000 tonnes.

At one point in history, Gilan began the largest single silk cocoon or thread maker and its prized shiny soft silk was exported to European markets with English, Dutch, French and Italian merchants competing to buy the thread or dried cocoons.

Making of Silk in Nature

|

| Fifth instar silkworm larvae. Image credit: Wikipedia |

In Iran, during the spring month of Ardibehest (late April), the process of spinning silk thread starts with silkworm breeders buying boxes of eggs of the silk moth, Bombyx mori (Latin for 'silkworm of the mulberry tree'). They place the eggs in a warm place or in an incubator to help speed the hatching of the eggs, a process that takes about ten days. The eggs will hatch into larvae called silkworms.

At the same time, mulberry trees will have grown new leaves which silkworm breeders buy to feed their silkworm larvae. in Iran, mulberry trees grow in Gilan, Mazandaran, Khorasan, Eastern Azarbaijan, Isfahan, Yazd and Kerman. Once the larvae hatch they eat the leaves of the mulberry continuously.

In Yazd, the town of Taft situated some 18 km southwest of Yazd city is a major silkworm breeding centre.

After the larvae (the silkworm) have moulted four times, that is when they are in the fifth instar, they loose their appetite and are ready to transform themselves into moths. To protect themselves while they are in a vulnerable almost motionless transformational pupa state, they enclose themselves in a protective cocoon enclosure. The cocoon is made out of silk thread, a continuous natural protein filament that they produce in their salivary glands and exude to form the filament.

The larvae's cocoon is built up from about 300 to 900 metres (1,000 to 3,000 feet) of silk filament. The filament is fine, lustrous, and about 10 micrometers (1/2,500th of an inch) in diameter. Each cocoon consists of about a kilometre of silk filament, and about 2,000 to 3,000 cocoons are required to make a pound of silk.

For the making of commercial silk thread, the cocoon's filament is unravelled. The filament from several cocoons are then passed over a pulley, wound together and spun into a thread. Two or three threads are in turn spun together to build a yarn and several strands of yarn can be spun further spun together to make a nett thread. Along the way, the yarn or thread is dyed if needed after which it is ready for weaving.

Suggested further reading:

» Top

|