Image credit: travfotos at Flickr

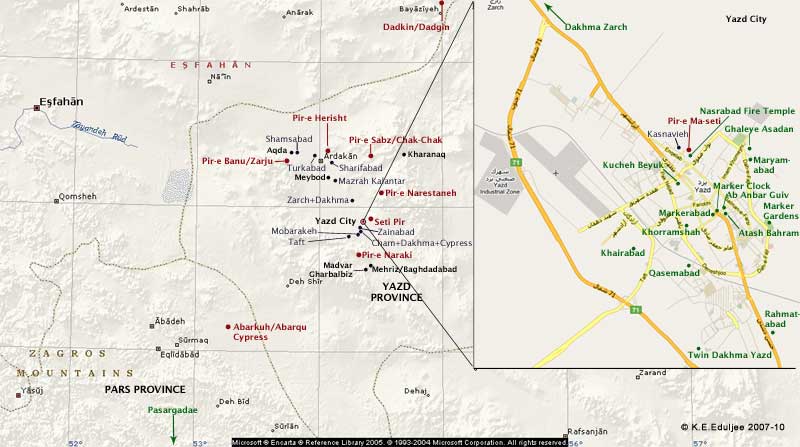

Page 3: Zoroastrians & Zoroastrianism in the Yazd Region

» Site Contents |

Suggested prior reading:

» Conditions & Treatment of Zoroastrians. 1500s to Late 1800s CE

» Irani Zoroastrian Renaissance. The Benefactors. Parsi Assistance

Further Yazd-related reading:

» Yazd Pilgrimage Sites

» Boteh (Paisley) & Aryan Trade

» Termeh - Heritage Fabric & Aryan Trade

» Kareez - Ancient Aryan Water Distribution System

» Yazdi-Zoroastrian Wedding Customs

» The Dari Language Project by Annahita Farudi and M. Doustdar Toosarvandani (pdf)

Zoroastrianism From a Yazdi Perspective

|

Zoroastrian Yazdi Ethic

After a visit to Yazd Iran, Karl Vick wrote in a June 18, 2006 article in the Washington Post: "Zoroastrians appear to enjoy the most respect (by the majority Muslims from amongst the other religious minorities) inside Iran... Zoroastrians enjoy a vivid reputation for honesty. Prices in a shop owned by a Zoroastrian are regarded as the benchmark that competing shops are compared against. Children are told that when arriving in a strange town near dark, seek out a Zoroastrian home to spend the night in. 'I'm sorry to say it and it might sound offensive, but these Zoroastrians are better Muslims than we are,' said Mohammad Pardehbaff, a Yazd driver."

[Despite these positive sentiments, discriminatory practices against Zoroastrians continue, and insults demeaning Zoroastrians are built into everyday language. For instance, a couples beliefs embedded in derogatory labels are that Zoroastrians worship fire (label: atash parast), but are Godless and do not pray (label: gabr - infidel). A traditional Muslim Yazdi rhyme names the five fingers, the thumb being called the gabr-e bi namaz, meaning the Zoroastrian without prayer.]

In his memoirs Yazd dar safarnameha (Yazd in Travelogues), Jalal'e al'e Ahmad writes in the section Safar-e be Shahr-e Badgir-ha (Journey to the City of Wind-Catchers), that in the city, "You see less thieves and beggars, you hear less profanity, insult and conflicts in the streets." In addition, a report published in the Keyhan newspaper (dated 17th Tir 1342, p. 15) states that of the forty prisoners in Yazd's jail, none were Yazdi, but that they came from elsewhere in Iran.

Dari Language of Yazd & Kerman

In addition to Farsi (Persian, the national language of Iran), the traditional language spoken amongst the Zoroastrians of Yazd and Kerman is called Dari, a name shared with the dialect of Persian spoken in Afghanistan. However, despite sharing the same name, the Dari dialects of Yazd or Kerman are quite different from the Dari of Afghanistan.

One explanation about the etymology of the name Dari is that it may have evolved from the word darbar meaning court, the implication being that Dari was the court language of the eastern Iranian lands (including Afghanistan) during the Persian Sassanid dynasty (226 - 651 CE). Another explanation is that before the Arab invasion of Iran, the languages of greater Iran were known to Iranians as Dari and not Farsi.

Eastern Dari

The following is a quote from our page on Haroyu (Aria, presently Herat and adjoining provinces in north-western Afghanistan): "The residents of Herat City are mainly the Parsiban (or Farsiwan), a group otherwise simply called Parsi (or Farsi), two versions of an ethnic term sometimes meaning 'Persian speaker'. However, all Afghani Persian speakers are not called Parsiban. For the main part, Parsiban refers to a sub-group of ethic Tajiks who speak Khorasani Dari, a Persian language dialect. [Khorasan is the northeast province of Iran that borders Herat and Afghanistan.] This is especially true of the rural Parsiban who have maintained the tradition of speaking Khorasani Dari. Members of the same ethno-linguistic group are also found in the Eastern Iranian provinces of Khorasan and Siestan / Sistan. Khorasani Dari is native to Khorasan, Herat and Farah provinces - provinces that were once part of Greater Khorasan. The eastern-most district in Herat Province is called Farsi / Parsi. There are about 600,000 Parsiban in Afghanistan out of a present population of just under thirty three million." Given that Khorasani Dari is spoken all along eastern Iran, from Khorasan to Siestan, and that many Zoroastrians from these areas migrated to Kerman and Yazd, carrying with them their language, the eastern Iranian connections with the Zoroastrians of Yazd and Kerman bear further exploration.

The eastern Iranian / Persian dialect of Dari that eventually evolved in Yazd and Kerman, cannot be understood by the speakers of Iran's national language, Farsi, a western Iranian / Persian dialect. The Zoroastrians of Yazd have not been very willing to teach non-Zoroastrians how to speak the language, using it to communication amongst themselves or when they did not want the Muslims to Yazd to understanding what they were saying. [The Dari speakers of Yazd know mainstream Farsi, the language spoken by Muslim Yazdis, as well.] E. G. Browne wrote in his book, A Year Amongst the Persians (1893), "This Dari dialect is only used by the guebres (see gabr above, a derogatory word that Muslims called Zoroastrians) amongst themselves, and all of them, so far as I know, speak Persian as well. When they speak their own dialect, even a Yezdi Musulman cannot understand what they are saying, or can only understand it very imperfectly. It is for this reason that the Zoroastrians cherish their Dari, and are somewhat unwilling to teach it to a stranger... To me they were as a rule ready enough to impart information about it; though when I tried to get old Jamshid the gardener to tell me more about it, he excused himself, saying that knowledge of it could be of no possible use to me."

Yazdi Dari Dialect

The principle Yazdi dehs 'villages' or neighbourhoods, have their own Dari variation that can sometimes be distinguished by the accent of the speaker, accents that can be quite 'thick'. While there are twenty-four such variations of Dari in use today, the Yazdis broadly group the different variations into the Sharifabadi and Mahlati dialects, Sharifabadi being the older and most difficult to understand while Mahlati is considered the more 'mainstream' dialect. Sharifabad is one of the oldest and most conservative of Yazdi villages. Mahlati is derived from Mahal-e Yazd / Mahale-ye Yazd, the Zoroastrian section of old Yazd city proper (the villages or neighbourhoods of Yazd are discussed further below.

Danger of Extinction

In their paper, The Dari Language Project, Annahita Farudi and M. Doustdar Toosarvandani quote Mazdapour (1995) as listing Deh-No, Deh-Abshahi, Ahmadabad, Shahabad, and Mehdiabad as some of the Dari varieties / dialects that have become extinct within the last thirty years. Given the diaspora and emancipation of Yazdi Zoroastrians, Dari is falling out of use within families.

» Further reading: The Dari Language Project by Annahita Farudi and M. Doustdar Toosarvandani (pdf)

Yazd's Zoroastrian Sites

The province of Yazd has Iran's only Atash Bahram, a fire temple that houses the highest grade of consecrated fire used in Zoroastrian worship. The Yazd Atash Bahram (also called the Yazd Atash Kadeh) is further described below. Yazd province is also home to the ruins of at least four dakhmas or towers of silence, as well as several pilgrimage sites. Many neighbourhoods and Yazdi towns have ancient Zoroastrian roots, and within Yazd city lie the Markerabad schools, clock and the Markerabad gardens.

There are archaeological sites that are now being identified as have a Zoroastrian connection. For instance, In Islamiyeh village near Taft, archaeologists have identified the the remains of an earthen wall covered with chopped straw and plaster inside a cave They believe the wall is part of a Parthian era (248 BCE-224 CE) fire temple.

Zoroastrian Villages & Neighbourhoods - Deh

The Zoroastrians of Yazd, even those living outside of Yazd, maintain a strong affiliation to their ancestral village or deh ('village' here also refers to the suburbs and neighbourhoods of Yazd city). When meeting for the first time, during introductions, Yazdi Zoroastrians seek to establish the village affiliation of the other. Each of the villages have a stereotyped characteristic attached to it and its members are similarly thought to have a stereotyped temperament. For instance, people from Sharifabad, one of the oldest villages, are thought to be the most conservative and orthodox, while those from Khorramshah are presumed to be wealthy. Qasemabad, the district closest to the Yazd city dakhmas (that are atop hills just outside the southern city limits) is a relatively new deh. Mahal-e Yazd / Mahale-ye Yazd, is the Zoroastrian section of old Yazd city proper. Recently, families from other dehs such as Maryamabad, Khorramshah and Qasemabad, have taken up residence in the mahale and therefore its residents are considered to be cosmopolitan and progressive.

In the past, perhaps in an attempt to remain as inconspicuous as possible and thereby avoid the jealous or angry attention of their Muslim neighbours, these dehs or neighbourhoods were fairly self-sufficient, independent and insular. These characteristic has changed dramatically in the last fifty years. As Zoroastrian Yazdis continue to move away from the traditional dehs, the latter have begun to suffer from neglect. According to Annahita Farudi and M. Doustdar Toosarvandani, the gardens or baghs of Qasemabad, sometimes used as summer retreats for the inner-city dwellers for instance, now "languish unkempt and overgrown inside their crumbling mud walls." In addition, they note that only a very few deh "residents still keep goats, as they all once did, housing them at night in the front rooms of their kahgel (straw mud) houses."

Turkabad, Home of the Mobedan Mobed

The high priest of Zoroastrians in medieval Iran was called the Mobedan Mobed, the Mobed of Mobeds. He was also known as the Dasturan Dastur. The inconspicuous seat of the Mobedan Mobed of Yazd was the town of Turkabad (also spelt Torkabad).

Turkabad is a town four kilometres northwest of Ardakan (Arda is related Old Persian arta which is in turn related to r'ta and asha). Turkabad is also fairly close to Sharifabad. Together they formed the spiritual home, not just of Yazdi Zoroastrians, but of all Zoroastrians in medieval Iran. While, two hundred and fifty kilometres to the southeast, the city of Kerman had its own Dasturan Dastur, they nevertheless acknowledged the supremacy of Yazd's Dasturan Dastur.

Turkabad remained the home of the Dasturan Dastur until he was compelled to move to Yazd city during the reign of the Nader Shah (1736-1747 CE), perhaps so that the high priest's activities could be better observed by the governor. During Nadir's reign many Zoroastrians were butchered.

Rivayats

In the mid 1400s CE, when Indian Zoroastrians sought authoritative answers to religious questions on orthodox Zoroastrian practices and observances, they journeyed to Turkabad. These visits would continue for nearly three hundred years and the answers to the questions would come to form the book of Rivayats, assembled by Ervad Bamanji Nusserwanji Dhabhar and published by the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, Bombay, in 1932.

The first visit to Yazd by a delegate from India was that of Nariman Hoshang whose patron was Changa Asa of Navsari (also see our page on Early Parsi History - Sanjan. Nariman spoke very little Dari/Persian and therefore had to live a year in Yazd, supporting himself as a small merchant, while learning enough of the local language in order for him to accomplish his mission. He returned to India 1478 carrying the answers and two pazand manuscripts and a long letter. Over the next 300 years until 1773, another twenty-five messengers made that journey despite great danger to themselves.

Sharifabad's Shah Bahram Izad Pak - Oldest Existing Consecrated Fire

Close to Turkabad, the village of Sharifabad became the home of not one, but two of rescued consecrated eternal fires or Atash Bahrams. When they were brought to Sharifabad, in order that they may escape the attention of those that sought to extinguish them, they were housed in non-descript mud houses indistinguishable from houses in the neighbourhood. Western traveller and author Chardin, writes that the Zoroastrians bought peace by remaining as inconspicuous as possible and by making generous 'presents' to the authorities and mullahs. The humility of the fire's home and the lack of ostentation or grandeur came to exemplify the Yazdi Zoroastrian spirit.

One of the two Sharifabadi fires was called the Adur Khara, said to be related to, or taken from, the Adur Farnbag of old (the words Adar and Atash are synonymous. Both mean fire). The other was the Adar Varharan (also called Shah Adar Varahram Izad), later called the Atash Bahram, rescued, according to Masoudi, from Istakhr. At Sharifabad, the two fires were united as one, the Shah Behram Izad Pak, and we understand that today, the united fire has its home in Yazd city.

[Etymology of Bahram (or Behram): Middle Persian Varharan from Avestan verethrakhnahe or verethraghna meaning victorious and verethra meaning victory or that which repels a foe.]

Hiromba

The festival of fire called Hiromba (making bonfires), elsewhere celebrated as Sadeh, takes place in Sharifabad (or nearby Pir-e Hirisht). In 2006, the festival was celebrated on April 15, when about 3,000 Zoroastrians from all parts of Iran including Yazd, Kerman, Isfahan, Shiraz, and Tehran gathered to take part in the ceremony. The participants reportedly brought wood with them to feed and sustain the fire. At the close of festivities, they took parts of the fire placed in a censer back home with them. Hiromba may be a local Yazdi version of Sadeh and the difference in dates may be because traditional Yazdis use the Qadimi rather than the Fasli calendar (see types of calendars in our Calendar page).

Yazd Atash Bahram / Atash Kadeh

|

| The eternal fire at the Atash Bahram, Yazd, Iran Credits: Various - photographer unknown |

The name Atash Bahram (Victorious Fire) more accurately defines the grade of consecrated fire in the temple, than it does the temple. However, the name has now come to mean the temple that houses the highest grade of fire used in Zoroastrian worship (also please see our page on Atash Bahrams). The Yazd Atash Bahram is said to be Iran's only temple housing Atash Bahram. However, the fire temple in Sharifabad, did house an Atash Bahram, and if that fire has been continuously maintained, then its temple would also be an Atash Bahram. The plaque of the Yazd city temple calls the temple an Atash Kadeh (Fire Temple) a more general name for a temple containing a consecrated fire (temples without consecrated fires are called Dar-e Mehrs or Darbe Mehrs).

In addition to the current existence of an Atash Bahram in Sharifabad, there are two Yazd city Atash Bahrams of which we have a record: the old Atash Bahram renovated by Maneckji Limji Hataria and the present or modern Atash Bahram. It is sometimes quite difficult to separate references in literature between the two. Once again, if the fire in the older temple has been maintained, then it too is an Atash Bahram, giving us the possibility that there may exist (or have until very recently have existed) at least three Iranian Atash Bahrams.

Prof. John Hinnells in his article at Encyclopaedia Iranica citing (Patel and Paymaster*, I. p. 83) states; "N. Kohaji (d. 1797), an agent for British ships coming to Surat, built a structure for the sacred fire in Yazd and sent the sacred fire from Surat to Yazd by road and purchased two properties to cover its upkeep." Since Kohaji died in 1797, the installation of the Surat fire brought in Yazd likely occurred in the mid 1700s. [* B.B. Patel and Rustam B. Paymaster, Parsi Prakash, vols 1-7, Bombay, 1888-1942.]

Maneckji Limji Hataria's Role

Maneckji Limji Hataria (1813-1890 CE) was the representative of a Bombay society, the Society for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Zoroastrians in Persia set up for the express purpose of helping the Zoroastrians of Iran who were subject to oppression and humiliation by the then Qajar (Iranian) government and locals. He arrived in Yazd in 1854 CE and immediately set about assisting Iran's Zoroastrian communities. In his book Travels in Iran - A Parsi Mission to Iran (1865), [translation at fravarhr.org] Hataria notes "In the whole country of Iran, there are, today, two Atash Bahrams (he mentions elsewhere the Atash Bahrams of Yazd and Kerman) and 17 Adarians (Atash Kadehs). It is imperative to raise a suitable funds for the maintenance of these religious abodes."

Renovating the Atash Bahrams in Yazd, in particular the Atash Bahram in Yazd city, became one of Hataria's first projects.

In his book, Maneckji Hataria goes on to note that the various challenges faced in maintaining the places of worship. "Long ago, the late Seth Ardeshir Dadiseth sent money and material to rebuild the Adarian at Mubaraka (we presume this is the Mubarakeh just south of Yazd enroute to Taft - see map above) and in order to obtain money for its maintenance, he purchased land nearby and let it on hire so that the rent could be used for the maintenance of the said Adarian. Today that said plot of land and the constructions thereon have gone out of the hands of the trustees and the Adarian is in a sad plight. If it is not repaired on time, it is likely to collapse some day."

If the external threats were not bad enough, there were problems from within the community as well, for Hataria tells us that "the late Seth Khurshedji Cawasji Banaji gave a donation for the construction of a public hall where religious ceremonies could be held and the hall could be used for other social gatherings. But the mobed in charge utilized it for the permanent use of his family members and their descendants and thus no trace even of the name of the donor is to be seen or found. This is a sad story."

Further, "in the vicinity of the Atash Bahram of Yazd, the Parsees purchased a plot of land with the intention of building a dharamashala in future. That proposed dharamshala is not yet constructed."

Elsewhere in Hataria's book, and in subsequent records, we read that despite all the challenges faced in trying to help the Yazdi community, the Parsi and Irani benefactors did not loose faith that eventually some good would arise. Today, the Zoroastrian community in Yazd is well served by all the schools, places of pilgrimage and worship, halls as well as several community facilities that have been preserved and built. They institutions and facilities have been critical to Yazd's Zoroastrian community strengthening its foundations. As a result, the community is well positioned to face the future.

|

| The bronze bust of Limji Hataria outside the Yazd Atash Bahram. Image credit: fravahar.org |

The Zoroastrians of Yazd acknowledged his contribution by casting a bronze bust of Hataria presenting placed outside the new Atash Bahram. According to Mary Boyce in her article Maneckji Limji Hataria in Iran in the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute Golden Jubilee Volume,

(Bombay, 1969), "There is only one piece of modern Zoroastrians sculpture in Iran, and that is a fine bust of Maneckji Limji Hataria, set on a pedestal outside the Atash-Bahram of Yazd. This catches well his air of benevolent but sturdy intrepidity. Behind it is the stately brick building of the new fire-temple, set high in a garden. In front of it, across a broad metalled road, are the spacious modern houses of wealthy Zoroastrians. The scene would be wholly strange to Maneckji, but with its air of tranquil security, very pleasing, a testimony in itself to the effectiveness of his life's work."

Also see: Maneckji Hataria's role in setting up a modern education system in Yazd.

Old Atash Bahram / Atash Kadeh

Professor Mary Boyce who we have quoted above, states in the same article that "the inscription in the old Atash-Bahram building at Yazd. dated 1855, shows that one of the first tasks which he (Hataria) undertook was the repair of this ancient sanctuary. The Muslims often forbade the Zoroastrians to repair buildings; and it is characteristic of the resourceful Maneckji that, less than a year after his landing, he somehow managed not only to restore but even to enlarge this very important fire temple."

Apparently, this Atash Bahram had been built with funds sent from India. In his book Travels in Iran - A Parsi Mission to Iran Hataria states, "the late Seth Noshirwan Koyaji got an Atash Bahram built at Yazd and for its maintenance purchased a plot of land named Bag-e-Chinaar and gave it on hire. But the party using the land refused to pay rent and became the owners of the land. Thus the income for the maintenance of the said Atash Bahram stopped and the Atash Bahram is now in a sad plight; it requires immediate attention."

Present Atash Bahram / Atash Kadeh

The plaque at the Yazd Atash Bahram / Atash Kadeh states:

"This Zoroastrians' temple was built in 1934 in a site belonging to the Association of the Parsi Zoroastrians of India under the supervision of Jamshid Amanat. The sacred flame, behind a glass case and visible from the entrance hall, has apparently been burning since about 470 CE and was transferred from Nahid-e Pars temple to Ardakan (a town some 60 kilometres north of Yazd city) then to Yazd (city) and its present site."

The temple was built according to plans prepared by architects of Bombay. Jamshid Amanat records in his memoirs that he had to make five trips to India soliciting funds from the Indian Zoroastrians. On four occasions, he travelled by steam ship and on one occasion he had to resort to travelling by camel through Baluchistan and the intervening deserts. It appears that the final donors included Homa Bani of Bombay, the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration Funds accumulated by the Zoroastrians of India, and the Parsi Panchayet (different authors give us different names and it is conceivable and there were several donors). Jamshid Amanat and his brother also made some donations in the name of their father Ardeshir Meheraban Rostam Amanat.

When Jamshid Amanat had secured the necessary funds from India, he set about supervising its construction. The temple was was opened on November 1934.

[An article at Vohuman.org gives us a different account but they might to referring to a different Atash Kadeh in Yazd city. The article states "Vicaji Ardeshir Taraporewala, a leading architect of Bombay, prepared plans for the Atash Bahram of Yazd. This Atash Bahram was built at a cost of Rs.31,823/- by the trustees of the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration Fund, Bombay, on lands donated by the sons of Ardeshir Mehraban, Dastur Rashid Shahriar. and Dastur Namdar Shahriar, The Atash Bahram was officially opened by Arbab Rustam Guiv on June 3, 1944." Ardeshir Meheraban Keikhosrowi was also the father of Morvarid who would wed Arbab Rustam Guiv.]

The fire now burning in the Atash Bahram was originally the Verahram Izad fire from the Pars Karyan Fire temple in southern Pars district of Larestan. The date of its consecration is recorded as 470 CE. From there it was transported to Aqda, Yazd, where it was housed for about 700 years. In 1173 CE, the flame was transferred from Aqda to the Nahid-e Pars temple in neighbouring Ardakan where it remained for 300 years. In 1473 CE the flame was transported from Ardakan to Yazd and maintained in the house of high priest Tirandaz Azargoshasp in Yazd's Khalaf Khan Ali district. Finally, the fire was brought to the present Atash Bahram upon its completion in 1934 CE.

|

Additional images. Precise location or identification unknown:

|

|

|

Dakhma

|

| Disused tower in Yazd, Iran - view from the ground. In the foreground, are the khaiele, buildings belonging to individual communities and used for monthly remembrance prayers |

There are several disused towers of silence, dakhma, in the vicinity of Yazd city. All are on top of small hillocks. The better known of the set are a pair just south of the city in Safaieh district. Another is located west of the Yazd city and north of Zarch. The fourth is located close to the village of Cham.

The system for the use of the twin towers south of Yazd was that when the ossuary well at the centre of the dakhma platform filled up, they caretakers would switch to using the other towers while the bones in the ossuary were dissolved. The fact that there was a need for two towers to be used in conjunction indicates that the population of Zoroastrians in and around Yazd city was large enough to require this system.

Maneckji Hataria in his book Travels in Iran - A Parsi Mission to Iran (1865) states, "The dakhma of Yazd was in a ruinous condition. A new dakhma on the top of the hill was constructed by the efforts of the Zoroastrian Anjuman of Bombay; but still the mobeds of the old school prefer to use the old dakhma, saying the new one was constructed in modern style and thus was not in keeping with our religion. As the new one is constructed with stone walls and the old one has muddy walls, the uneducated mobeds believe that the real dakhma must have muddy walls only. Stone walls are modern, adopted from western countries, and thus they are unfit for a dakhma." Nevertheless, reason prevailed and both dakhmas were used.

In 1937, Tehrani Zoroastrian established a cemetery called an aramgah, a place of rest, and in doing so soon abandoned the use of the Tehran dakhma built by Maneckji Hataria. The graves were lined by concrete in order to prevent contact, and therefore pollution, of the earth. In 1939, Soroush Soroushian, head of Kerman's Zoroastrian Anjuman (Society), lead a move to establish a cemetery in Kerman. However, some Kermani Zoroastrians, as a matter of personal preference, continued to stipulate that their bodies be consigned to their dakhma, until that dakhma was finally closed in the 1960's. The Zoroastrians of Yazd, traditionally, the most orthodox of the Iranian Zoroastrians similarly established a cemetery in 1965 at the base of the Safaieh district dakhma hills, and it was not long before the Yazd city dakhmas stopped being used. Sharifabad, near Ardakan, seat of Yazdi Zoroastrian orthodoxy continued to use their dakhma into the 70s, when the Iranian government prevailed on the Zoroastrians to stop using the dakhmas.

A video featuring an interview with an eighty-four year old salar cf. nasa-salars), the person who helped carry the last body into the Yazd dakhma, can be seen at IranNegah.com.

In the interview, the salar said that each Yazd city Zoroastrian neighbourhood (formerly villages around Yazd city) had a mortuary (genzoog?) where the body of the deceased was bathed, wrapped in a shroud and then taken to the towers of silence. The buildings at the base of the tower hills were called khaiele and each belonged to one of the Yazdi neighbourhoods such as Khairabad, Ghasemabad and Rahmatabad. Once a month, members of the community gathered in the buildings to share food and pray for the departed.

For further information, please see our page and section on Towers of Silence.

|

| The twin towers of silence south of Yazd city, Iran |

|

Treatment of Zoroastrians in Yazd and Iran

Early 1700 - Late 1800 CE

While conditions for Zoroastrians in Iran were difficult enough after the Arab invasion, conditions reached the depth of despair in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Of these two hundred years, an article The Zoroastrian Houses of Yazd in Vohuman.org by Ryszard J. Antolak (an article review from Vladimir Fedorovich Minorsky memorial volume) states "whereupon two hundred years of political and religious turmoil ensued which decimated the population. Yazd suffered attacks from Afghans, Zands and Afshars, to name but a few. The Zoroastrian population was subjected to additional hardships. As a religious minority subject to discriminatory laws, it found it had as much to fear from its Muslim neighbours as from the foreign forces armed against it.

"In 1963 when Mary Boyce arrived in the region to study them, she discovered gloomy, fortress-like buildings virtually devoid of any furniture or greenery. They were low and airless. No badgirs adorned their roofs. The primary consideration of the builders had been defence. The ideal solution would have been to build upwards, erecting high, tower-like houses as are found (for example) all over Scotland. But in Iran, Zoroastrians were not allowed to build their homes any higher than a man could reach (or any taller than the houses of Moslems). They could only build downwards, creating dark honey-combs of subterranean rooms with adobe walls several feet thick to withstand attack. The Zoroastrians were physically greater in stature than their Moslem neighbours ("mighty men", as Mrs. Boyce calls them) and they could have put up a fight if they had to. But it seldom happened. The penalty for killing a Moslem was certain death: to kill a Zoroastrian meant incurring only a modest fine, usually waived by the authorities. Better, therefore, to prevent attacks in the first place

"Entry to the houses was via a single door from a narrow lane just wide enough to allow a fully-laden donkey to pass. The Law stated that the door of a Zoroastrian dwelling could be secured by only a single hinge, so a series of doors had to be built (one after the other) to prevent forced entry. Finally, at the end of a gloomy corridor, a narrow door - the smallest of them all - led into a bare, central courtyard or rikda.

"There were no windows. Sometimes glass bottles could be seen protruding from the walls of the entrance lane. But these served as spy-holes rather than windows, defence being uppermost in the minds of these persecuted inhabitants. The only light to enter the house was through the tiny courtyard or via irregular gaps in the doors or ceilings. In some of the buildings the courtyard had been covered over completely to prevent intruders gaining access from the roof. The result was total darkness and oppressive claustrophobia. It is ironic that Zoroastrians, with their sophisticated theologies of light, should have been forced to live in such shadowy, enclosed buildings."

An article in tenets.zoroastrianism.com titled Zarathustri Pilgrimage Sites In Iran states "Prof. Edward G. Browne in his A Year Amongst The Persians (the year being 1887-88). 'Upto 1895, no Parsi was allowed to carry an umbrella. Up to 1895, there was a strong prohibition upon eye-glasses and spectacles; up to 1885 they were prevented from wearing rings; their girdles had to be made of rough canvas, but after 1885, any white material was permitted. Up to 1896, the Parsis were obliged to twist their turbans instead of folding them. Up to 1898, only brown, grey and yellow were allowed for body garments but after that, all colours were permitted, except blue, black, bright red or green. There was also a prohibition against white stockings and up to about 1880, the Parsis had to wear a special kind of peculiarly hideous shoe with a broad, turned-up toe. Up to 1885, they had to wear a torn cap, up to about 1880, they had to wear tight knickers, self-coloured, instead of trousers. Up to 1891, all Zoroastrians had to walk in town and even in the desert, they had to dismount if they met a Mussalman of any rank whatever.'

"Browne writes about an incident in 1860 where a Zoroastrian man of 70 years went to the bazaar in white trousers of rough canvas. According to Browne's account, 'they (the Mussalmans) hit him about a good deal, took off his trousers and sent him home with them under his arms.' "

Modern Challenges

|

| Walking hand-in-hand down a street in Cham, Yazd Image credit: Bahram Yazdani at Berasad Click on the link to view more images |

In modern years, a new threat to the survival of Zoroastrianism in Yazd has emerged - the lure of the big city of Tehran and immigration to countries of the west. Around the turn of the last century the estimated number of Zoroastrians in Yazd was in 1975 was about 10,000 individuals. In 1975, that figure was down to 4,000 (see our page on Demographics). The number of Yazdi Zoroastrians in Tehran was large enough for them to form their own cultural association.

A June 18, 2006 article in the Washington Post by Karl Vick states: "In Taft, 10 miles south of Yazd, only the elderly linger in the mud-walled warren of houses identifiable as Zoroastrian by the tiny oil lamps burning in glass cases fitted into walls. 'It's like we have leprosy, the way they've evacuated!' said Ardeshir Rostami, 83." There are other reports that in the old Zoroastrian villages, such as the village of Cham just south of Yazd on the way to Taft, travellers saw only senior citizens walking the streets.

At present, the greatest threat to Yazd's Zoroastrian heritage is no longer external. It is internal. The greatest threat is apathy within the community or concepts that ridicule the value of tradition.

Nonetheless, there may be a glimmer of hope that the trend can be halted if not reversed. A February 2010 report of a Jashne Sadeh festival in Cham states that the event attracted 5,000 people, both young and old, half of them being non-Zoroastrians.

|

Next page:

» Page 4: Zoroastrian Schools. Pioneers: Maneckji Hataria, Perstonji Marker, Mirza Soroush Lohrasb

Previous pages:

» Page 1: Yazd Region

» Page 2: Coping with the Desert. Innovative Technologies

Further reading:

» Yazd Pilgrimage Sites

» Boteh (Paisley) & Aryan Trade

» Termeh - Heritage Fabric & Aryan Trade

» Kareez - Ancient Aryan Water Distribution System

» Yazdi-Zoroastrian Wedding Customs

» The Dari Language Project by Annahita Farudi and M. Doustdar Toosarvandani (pdf)

Offsite:

» In Yazd with Edward Browne, Spring 1888 AD at Vohuman